Sex work in the age of social media

“You’re posting naked pictures of yourself online… some people find it to be so scandalous or shameful. I don’t know why, but I don’t have that view of it. Everything I’m doing is legal so. . .how much does society really care anymore?”

Sex work has diversified into a set of unique and separate professions through the growth of technology and social media platforms over the last five years. Full service sex work, otherwise known as prostitution, no longer encompasses every physical or nonsexual act that is defined as sex work. However, since many European countries are vague on legalizing, or at least decriminalizing sex work, the right to regulate goes to the platforms where workers conduct business. Thousands of profiles across Twitter, Tumblr, and Instagram can be found by simply searching certain hash tags like #sellingnudes. Try it sometime.

However, these sites are closing their doors on sex workers one by one, until they are forced out of an industry that may have been a last resort. This alienation serves to create a toxic environment for sex-workers, since already they only have their own community to support them, thanks to the lingering social stigma against nudity and sexual expression. But why does all this shame and hate against sex work remain when it is a consensual decision? It is hard to put it down to a universal desire to protect young women from being objectified by men. On the contrary, as quickly became clear in my interviews, the issue is the lack of control by men.

Over the course of a handful of cigarettes and a few cups of coffee in St. Mark’s Place, New York City, I talked with Eliza FemDom and Sophia Mask (their professional pseudonyms) about their popular division of sex work: selling nude photos and videos. Eliza also hosts live webcam shows. Known as a “camgirl”, she live streams herself on her webcam for clientele. They tell her what they’d like to see her perform live, offering a variety of acts that range from stripping to foreplay. Cam girls work remotely in a space they choose, and distribute their content on a platform of their choice. Eliza began her profiles on Chaturebait.com and MyGirlFund.com initially out of a necessity to make money, as she could not afford to pay for the transportation needed to maintain a job in a different industry. Yet within five months, her popularity rocketed. Soon she was streaming with over 10,500 followers tuning in, earning anywhere between $400-800 per show. I couldn’t afford to watch her show myself, so Eliza described how she stages it:

“For the cam show, I just go on, start in a bra and underwear, and have a menu if you want to see my boobs. It’s this much or whatever, and just wait for people to tune in . . . After a while I’ll put [clothes] back on, so people keep requesting and sending me money. I just do it as long as I want to. Usually, I do it for an hour or two.”

Webcam shows are a popular category on porn sites like Pornhub and RedTube, but Eliza does not categorize herself as a porn star. Her live streams cannot be recorded by any viewer, and nor can they be saved by the streaming website. This means that when the webcam turns off, there is no trace of the show other than the money put in her account. When asked if she would further expand her platform by beginning to work in porn films rather than webcam, she said:

“I’ve researched it and a lot of porn stars actually go from being porn stars to cam girls because when you’re a porn star, you sign a contract, and they can just make you do pretty much whatever they want you to do. Whereas with a cam girl, you’re in charge of your own image and you’re in charge of what you’re comfortable with, and your hours and things like that.”

After she finished her live streams, she messages clients through her DMs in Chatterbait, MyGirlFund, or her premium Snapchat account, earning a further $200-300 selling nude videos and photos of herself. Eliza has control over her prices, the longevity of her live streams, and the level of nudity she wants to offer. As she taps the ash from her cigarette, she mentions that sometimes she doesn’t have to be naked at all. She has been paid for videos of her smoking, putting on makeup, insulting customers, or other seemingly random, nonsexual requests.

Sophia Mask was introduced to sex work by Eliza, after struggling to maintain a job along with her course work in college. Unlike Eliza, Sophia covers the top half of her face during her shows, to prevent classmates and tutors from discovering her online. She started a Twitter account to sell her nudes in early May, and found some success within her first few weeks. Gaining over 200 followers on Twitter in two weeks, she earned an average of $100 USD per week by selling pictures. However, she quickly discovered that sex work was not for her.

The issue, she told me, was not so much with the clients, but with the apps she was using to conduct business. Money transferring apps, such as PayPal, Cash App, Circle Pay, and Google Pay allow quick, anonymous transactions, only requiring a username and a bank account. These apps can be utilized for personal transactions between friends, but also for small businesses to accept electronic payments. Unfortunately for sex workers, these apps prohibit the sale of “adult content”, often suspending accounts with little to no warning or evidence. Other violations that can trigger the suspension an account include gambling and drug dealing. This results in sex workers like Eliza and Sophia being treated as if they are committing a criminal offence. While explaining the autonomous power of these apps, Sophia said:

“There are other girls that lost a lot more than I did. I lost $100 which remains frozen in my PayPal account, and 200 followers, but other people had accounts with over 5,000 followers get removed, and had to start over. I worked every day on building up my following and one day it was just gone. When I called PayPal customer service, they wouldn’t explain why they froze my account or how they were certain I was connected to my Twitter profile, especially since I used a different name and covered my face. I felt like I was trapped in some conspiracy.”

Social media platforms like Twitter, Snapchat, Tumblr, and Instagram also delete accounts that depict nudity or potentially promote sex work. These platforms are a means for sex workers to advertise a wide variety of products and services, but their content is forcibly taken away at the slightest suspicion of sex work. Most workers do not post content that is considered explicit. They ask customers to direct message for a private viewing of their nudes, or link the websites with their content. One such website is the popular ‘Patreon’, where personalities like YouTuber Trisha Paytas sells nude photos.

Herein lies the hypocrisy: the selling of nude photographs and videos is a long-running international industry. Erotic photographs of women are sold through publications such as Playboy or Hustler, and are displayed on the shelves behind clerks at convenience stores next to the razors and tobacco. The models may not be immediately recognized as sex workers, but the content is the same. The only difference is the professional cameraman and crew, as well as the partnership with a hundred million-dollar corporation.

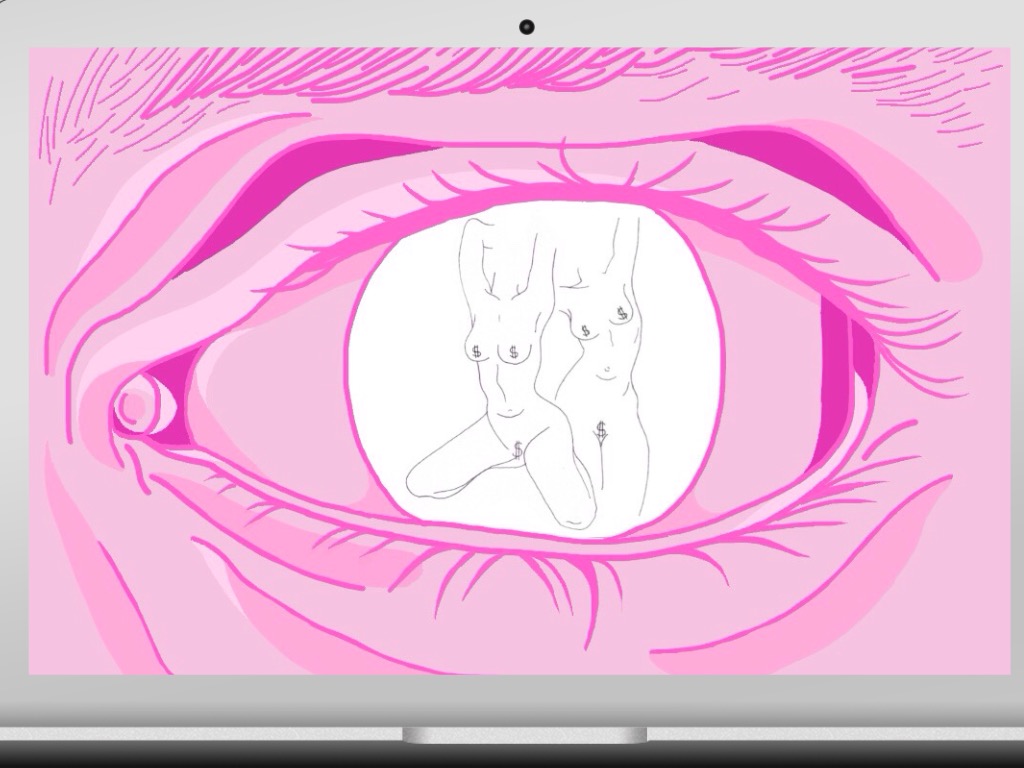

The double standard that lies within the widespread consumption of mainstream pornographic material was highlighted by the second-wave feminist movement. Artist and photographer Hannah Wilke 1974 created S.O.S Starification Object Series in 1974. The exhibit consisted of various nude self-portraits with gum stuck to her body. The poses mimicked catalogue contortions, exuding the sensuality of an editorial model, but juxtaposing the familiarity of magazine eroticism with the abnormality of the chewed up candy. The series mocked the male gaze by consciously posing in conventionally arousing positions, without any intent of arousing the viewer. Art critics judged Wilke’s nudes as narcissistic. They said that she was flaunting her beautiful body too much for it to be considered a feminist piece of art.

Like Hannah Wilke, Eliza and Sophia are their own photographers. They take their photos on their iPhones, and sell them directly to individual clients, thus retaining the power to distribute their content as they wish. They arrange their own lighting, and they have complete autonomy over their self-representation. They bear the sole responsibility for the creation and sale of their photographs. While this gives them creative freedom and agency over how they are viewed, it also means that they have no buffer against the prejudices they face. The mostly male Playboy photographers are not subjected to the same criticism and stigma that the women in the photo face, despite their involvement in the creation of the pornography, and their participation in sex work.

The objectification of women in nude photographs begins when her sexuality is captured by another person. She has become not the vision of herself, but the vision of the person behind the lens. In another example from nude art photography, Alfred Stieglitz did a series of naked photos of his fellow artist and soon-to-be-wife, Georgia O’Keeffe. In several of these naked photos, O’Keeffe is made an object of the male gaze, cupping her breasts or pinching her nipples as he directs. Yet Stieglitz remains the one recognized as the creator of the art, and will profit from her body as it is sold and gazed upon by thousands of people paying for an exhibit. She is his object and, therefore, she will not be persecuted for creating erotic content, as a man will be the one to profit off the sale of her beauty.

Like the feminist artist, Eliza and Sophia decide what they will wear, where they will shoot, how long they will shoot for, and what they’re willing to perform. It is, in its own way, a liberating and profitable form of sexual expression to wield their sexuality. When Eliza was asked what she would do if her account (under a professional pseudonym) became identifiable in her locality, she said:

“Yeah, I don’t think I’d be afraid if it got out. I don’t really like the stigma about the naked body. I don’t understand why it’s such a big deal, and why if I’m naked ‘it’s terrible’ and ‘it’s going to ruin my life.’”

And where is the shame towards the buyers of their content? The majority of Eliza and Sophia’s clients have the luxury of remaining completely anonymous. Furthermore, clients can weaponise their anonymity to try and scam sex workers. Clients try to evoke sympathy, claiming they were previously scammed by a sex worker out of their money, and ask for cheaper prices. Or they lash out at workers online by demeaning their profession. Sophia described the most common and detrimental scam tactic is clients asking to pay for content through exchanging banking info. That includes the account number and transfer info that can then be used to hack into the sex worker’s bank account to rob her. Sophia goes into further detail about other ways men online have tried to take advantage of her:

“Starting off, I kept getting scam accounts. These guys would ask for a ‘preview’ of my nudes, essentially asking for free pics. Or they ask for pics first and say they’ll pay me after, which is so stupid. Would you walk into a store, take stuff, and then say you’ll pay them back? The worst guys claim they are sugar daddies, giving out thousands of dollars for no sex, and then ask for my banking info, which Eliza told me was a big red flag.”

The progressive narrative of female empowerment and sexual autonomy creates an expectation that workers like Eliza and Sophia are in control of their sexuality and their work. Yet this feeling is limited by the fact they cannot announce their accomplishments without the backlash of their accounts being shut down, thus cutting off sources of revenue for their business. It is time, then, to rethink societal attitudes towards sex work, understanding it as another facet of the mainstream nude. Currently, ideas of embracing femininity and womanhood are exempted when it comes to utilizing sensuality for profit. All the while, editorial photographers are profiting from eroticism through national print media. The issue clearly lies with the agency of the woman as opposed to her nudity. In 2019, a woman’s sexuality is still only acceptable when validated by the male gaze.

Words by Evalena Labayen. Art by Eve Rooney.