On the front lines of the migration crisis in Palermo

In the Kalsa neighbourhood of Palermo, between the city’s historic centre and its seafront and ports, you’ll find Piazza Rivoluzione. A square that is more of a triangle, the piazza is a meeting point for five winding streets. At its heart currently stands a mass of scaffolding and tarpaulin, a plastic pillar, tall and white, right in the place where you’d expect a fountain or a monument. I’m told that there is in fact a fountain here but it’s undergoing restoration; specifically, on the sixteenth-century statue of the Genio of Palermo that sits on it. Cut by an unknown artist in Carrara marble, the Genio (Genius) looks up to the mountains on the southern horizon, holding a feeding snake to his breast; a symbol of the city providing for, teaching, and transforming everyone that comes to it, foreigners and locals alike.

Palermo is the capital of Sicily, an autonomous region in southern Italy famously proud of its multifarious history. Palermitan identity is based on a long, cobbled-together culture formed through centuries of foreign rule. First came the Phoenicians, then the Greeks, the Romans, the Ostrogoths, the Romans again, the Arabs, the Normans, the Germans, the French, the Spanish, until finally Sicily was marched on by Garibaldi and joined with the other Italian regions in 1860, forging modern Italy as we know it today.

If you look at a map, Sicily is the football being kicked by the tip of Italy’s boot. It’s one of the southernmost parts of Europe, a sun-warmed island with only the Mediterranean Sea separating its coasts from those of Tunisia, Libya, Algeria, Egypt, Israel, the Gaza Strip, Lebanon and Syria. In the last six years, nearly 750,000 people have successfully crossed that sea to reach Sicily. Migrants largely originating from war-torn and poverty-stricken regions travel for months at great personal cost, just to get stuck in an overpacked vessel in the Mediterranean, in the hope they’ll be rescued by Italian forces.

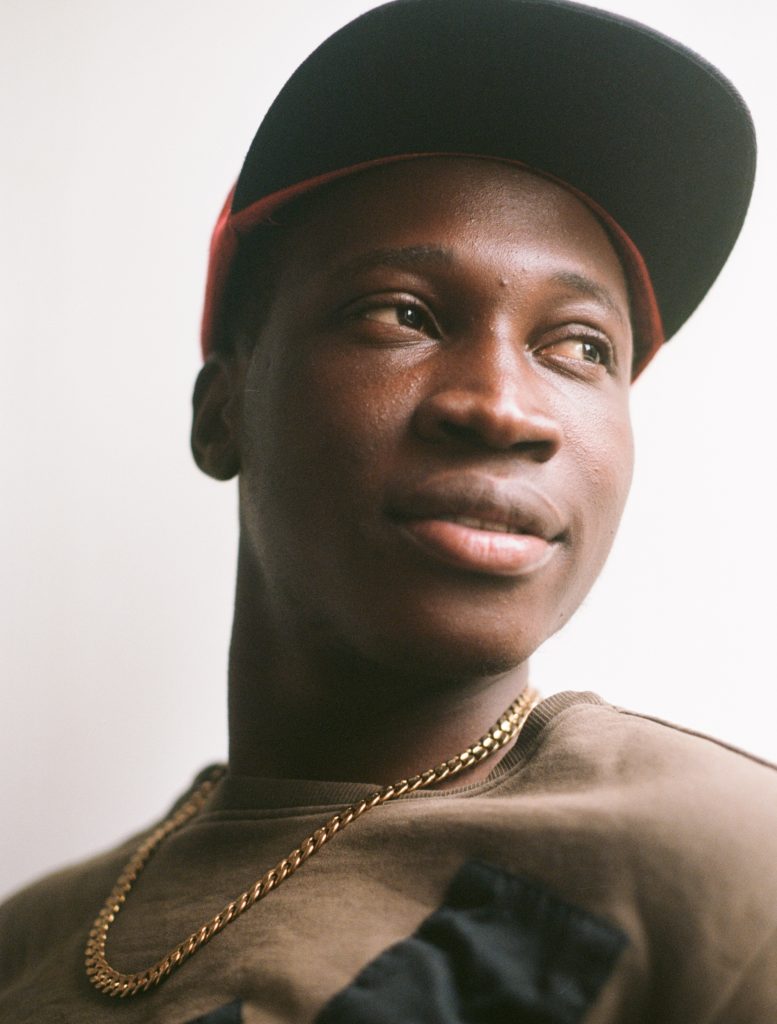

I travel to the edge of the city, to a huge, near-derelict psychiatric hospital complex next to the autostrada. It’s been taken over by the SPRAR (in English: Protection System for Asylum Seekers and Refugees) and is now a centre for refugee and asylum-seeking minors run by local authorities. Finding the SPRAR means navigating identical lots of connected convent-like structures, all with shuttered windows that look over overgrown cloisters and courtyards. Deep in one of the buildings, I’m finally led to what looks like a children’s wing at a hospital. Waiting for me is Bakary, a Gambian migrant who has lived in Palermo for just under three years. He’s only eighteen now. After deciding to leave his home in Gambia, it took Bakary nine months to reach Sicily in the winter of 2016. “There were maybe 120 of us,” he tells me. “We spent four to five hours on the water, which was really lucky.” He says that his boat set off from the coast of Libya but leaves out further details of the journey. After being rescued from the sea to the West of Trapani, Bakary was brought to Palermo and has since made a name for himself amongst social workers for his interest in journalism, particularly related to migration issues. I’m introduced to him by my aunt Emma and her co-worker Yodit, both of whom work at the SPRAR. They are some of the very first people who migrants and asylum seekers meet when they arrive at the city. When I ask why he came here, Bakary is concise: “I think it’s better than my country; there’s freedom of speech here, freedom of movement. We have more opportunities.”

In 2018, Italian Prime Minister Matteo Salvini described Sicily as “the refugee camp of Europe.” Inflammatory, but not particularly shocking, Salvini’s language shows the recent trend of European (not to mention British) politicians adopting increasingly hostile rhetoric around migration. Bakary is one of the many people, demonised as part of “a swarm” by David Cameron in 2015, who undertook the precarious journey by boat across the Central Mediterranean. Nigel Farage’s notorious ‘BREAKING POINT’ billboard, which depicted a queue of brown-skinned migrants and bore unsettling similarities to old Nazi propaganda posters, was a clear litmus for just how toxic the rhetoric of xenophobia at home had grown. Whilst the likes of Cameron, Farage, and Salvini can drop the crise-du-jour of migration as quickly as they picked it up from the comfort of their seats in London, Brussels, and Rome respectively, for Palermitans, migration has always been a fact of life to which they’ve adapted, rather than a distant fear capitalised upon for political scaremongering.

Palermo’s mayor is Leoluca Orlando. He famously entered politics following the death of his friend, the President of Sicily, Piersanti Mattarella, who was murdered by the Mafia in 1980. The murder catalysed a long resistance to political corruption in the 1980s and 90s, and Orlando was on the Mafia’s death list alongside judges Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, who were both killed in bomb attacks in 1992. Now Orlando is taking on another huge task to continue his anti-mafia efforts; he is famed for his pro-immigration stance and known for personally welcoming the ships that arrive at the city’s ports. His logic is based on the knowledge that penalising migrants and frustrating access to citizenship only fuels the Mafia’s absorption of illegal arrivals into their drug gangs. In every interview I can find, Orlando invariably touches on two central tenets: “Palermo is open” and “There are no migrants in Palermo. Everyone in Palermo is Palermitan.” Because of Orlando, migrants have access to medical care and education after living in Palermo for only two months. This approach has fostered a newfound cultural pride in the city; one that values hospitality, multiculturalism, and change, and that has laid foundations for new arrivals to build a life in Europe.

“Looking at us from England, you must think we’re mad […] but we’re not. This city is full of contradictions. It’s poor but it’s rich. We have plenty. We live well. It’s so dignified. It’s a city that has always fought for its life. It’s defended itself; there’s a different story here to yours.” Emma speaks with love as she describes her hometown over lunch. We’re eating at Moltivolti, a restaurant-cum-workspace for NGOs and freelancers working with migrants. The kitchen is entirely migrant-run. It is situated in Ballarò, one of the most ethnically diverse parts of the city, and offers a half-Sicilian, half-foreign menu: between us we order dishes from Palermo, Afghanistan, and Senegal. She’s brought me to meet Yodit, her colleague and project coordinator at the SPRAR, who later introduces me to Bakary. “I’m not a citizen but I feel like one,” Yodit says. She was still a child when she arrived in Palermo from Ethiopia thirty years ago. “For me, migration is both personal and political […] I may have been born in another part of the world, but I always say: Palermo didn’t just happen to me, I chose Palermo. I chose to make it my home.” To Yodit, Mayor Orlando’s pro-immigration stance isn’t purely altruistic, it’s rightly self-interested: “He’s not just respecting human rights, the thing he’s really dealing with is the security of his own city. So many other mayors are following our example now in opposing the current government. If you make arrivals uncomfortable, make it a struggle to find work, to rest, to live, that’s what creates chaos, anger, suffering, and frustration. It’s a huge security flaw.” When she speaks about her work, Yodit reframes the language around migration: “the principle objective of our work here is to follow these kids on their journeys of ‘autodetermination.’” On this last word, Yodit pauses and looks at me with real intention. She’s been hitting the table as she speaks. “I prefer ‘autodetermination’ as a term. I like to use it instead of ‘integration,’ or even ‘interaction.’ ‘Autodetermination’ is about letting these kids show what skills they have, working on what they’ve got and what they lack, orienting themselves. We accompany them along a small part of the journey, but as they grow up, they stray into completely new territory without us.”

For Yodit, the people who come through the doors of the SPRAR are no less Palermitan than she is: “It’s a lottery where you’re born.” A few days earlier, I spent the day walking the city’s immigrant neighbourhoods with a twenty-seven-year-old called Giorgi: ‘Giorgi from Georgia.’ He came to Palermo as a teenager and is now training as a social worker and cultural mediator with my aunt Emma. We find one another on the steps of the Teatro Massimo, where I’d been sitting under an olive tree. Within a few streets’ walk away, we’re dodging the traffic of shoppers and talking quickly. We end up at the edge of the Ballarò street market, one of many markets which divide up the week for Palermitans. Nestled low between sunlit palazzos and churches, it is a maze of stalls heaving with meat, fish, fruit, vegetables, clothes, trainers, household items and more. The sellers spar with their voices, punches of ‘buongiorno’ ringing across the crowds of shoppers, listing everything on offer. At times, the vocal competition grows so fierce that their booming calls drown out our conversation.

“They’re so beautiful, so colourful,” he muses, though I can’t tell if he’s talking about the markets or the people; I’d been told proudly by my grandmother that if I went to Ballarò, I’d see Palermitans and foreigners working side by side. As a cultural mediator, Giorgi spends his time explaining Palermitan culture to new arrivals, as well as helping them understand one another’s cultural backgrounds as they settle in to the city. He talks to me at length about candlelit dinners out on the city’s streets, where people share food, music and poetry. I ask him if it’s easy to be Palermitan and he squeals a long “yeeees” in response. “I am Palermitan. I’m so proud to live in this city. To be Palermitan is to be so many different things. It’s liberating here. The colour of your skin, who you’re into, where you’re from […] it’s a non-issue. What you are on the inside: it’s all the same.” Giorgi is part of a new generation of Palermitans taking root in the city centre, Sicilians and foreigners alike, whose politics are perhaps even more liberal than their hospitable predecessors. “The youth have got more space of mind, more ways of thinking, bigger, higher dreams. There’s a complexity in their approach. The mindset of the youth is, in my opinion, so unrestrained. A change is going to come. It’s only just starting.” While it would be easy to turn this into a story of young against old, or a generation taking over those before them, Yodit sees the current climate as part of one long tradition of accoglienza, most closely translatable as ‘hospitality’: “Sicily is in the Mediterranean. It’s in our geography. It’s in our history. It’s part of our nature, part of our DNA, to be a centre of movement, of transformation. Sicilians have always been familiar with this flux, this change. They’ve always fought for justice, for fortune, there’s always been a different take here.”

“I’m convinced that immigration is a phenomenon that no one can stop. It’s pointless to try. You can invent laws, you can pass acts, anything you want. But no political force, whether Italian or European, can stop it. Mobility, the sense of movement – it’s an intrinsic human right embedded in every person.” ∎

Words and Photographs by Antonio Perricone.