Harder Than Harvard

Whether Harvard actually does discriminate against Asian applicants (it does), and whether repealing affirmative action really will solve that (it won’t), the most notable issue in Asian American politics right now is a fight about who gets into Harvard University. The fight for Asian representation at elite institutions continues at the expense of black and Latino students, for whom the crushing intersection of class and race means that they are far less likely to be accepted at Harvard. Asians blend into whiteness better. They are more easily placed alongside white students in a world where attaining whiteness is, more often than not, the ultimate marker of successful social mobility.

In 2015, Chinese-American police officer Peter Liang was indicted for fatally shooting an unarmed black man, Akai Gurley. Protests erupted across the United States, as Chinese-Americans demanded “Justice for Peter Liang”. Although Liang had murdered Gurley in cold blood, many argued for his release on the grounds that white officers had not been punished under similar circumstances. Whether the court’s verdict was just or not, the way in which many members of the Asian-American community responded to Liang’s sentencing serves as a fascinating litmus test for contemporary race relations. ‘Justice’ in these cases appears to mean attaining the same level of privilege as white people: ‘if white people can do it, why can’t we?’

In the black-and-white dynamic of countries such as the US or South Africa, Asians have always occupied an ambiguous position. In 1839, the Siamese twins Chang and Eng Bunker obtained legal status equal to whites, married white women, and owned African slaves on their plantation in North Carolina. They were successful too, funding their lavish lifestyle through investments of more than $60,000 dollars (equivalent to £1.5 million today). On the other side of the Atlantic, Asian South Africans who were descended from Chinese, Indian and Indonesian shopkeepers, were classified as ‘Coloured’ during apartheid, whereas those recently arrived from Japan, Korea and Taiwan were deemed ‘honorary whites’, escaping forced relocations, armed police raids, and a plethora of other barriers in society. The latter group furnished South Africa with a lucrative trade in foreign electronics and luxury goods, and thus had a higher social worth attached to them. Immediate economic value translated into social mobility: the market dictated your place in society.

There is much that remained peculiar to the social status of Asians in South Africa. Chinese communities in particular occupied a specific in-between position well into the twentieth century. In the 1970s, official attempts to attach full ‘white’ status to Chinese South Africans were rejected by the very demographic such legislation would supposedly emancipate. Chinese people were reluctant to give up their unique ‘Chineseness’ for a homogenous whiteness, even in the midst of a horrendous apartheid. The idea that Chinese South Africans were heirs to a rich Confucian culture was not only a source of community pride, but was also used as political leverage. In 1985, they were allowed to purchase land in historically white areas without permits. This was partly due to Chinese insistence that they were far better behaved than other minority groups and black South Africans. In this vein, many Asian South Africans actively campaigned to retain their in-between status.

East Asians have been toeing the race line for centuries. Even today, in an age where government legislation seldom discriminates explicitly on the basis of skin colour or ethnicity, their experiences reveal the total arbitrariness of whiteness. It goes without saying that being ‘white’ isn’t a biological identity but rather a socio-political one, replete with a long history of exploitation stemming from the colonial era.

The idea of whiteness was constructed for social control. It does this by establishing an us-versus-them dynamic. Orientalism was a cultural means of setting up the East as the West’s opposite, helping to define ‘white’ European identity at the dawn of imperialism by constructing an irreconcilable Other. The subordination of indigenous populations – from Ireland to Papua New Guinea – was pseudo-scientifically justified on the basis that the ‘white’ coloniser was inherently more civilized and developed than the subjugated Other.

Whiteness is a fluid category which has always been deeply intertwined with class. In many settler colonies, workers from a range of ethnic backgrounds intermingled, including ‘white trash’ groups who had been deported to the New World from Europe itself. Whiteness as an ideal of superiority undermined solidarity amongst predominantly impoverished settler communities. The indentured white workers, often deported convicts who were sentenced to years of labour as ‘repayment’ for their crimes, considered themselves superior to the black slaves around them. And yet, white elites in those very same settler communities viewed them as even less human than the enslaved Africans and a stain on the white race as a whole. In the words of Nancy Isenberg, author of White Trash, certain white workers were classed as ‘waste people’ and conceived as ‘evolutionary stagnant.’

When the Irish first began to immigrate to the United States, they too were laborers, who, like English ‘white trash’, were seen as violent and biologically inferior. Popular media envisioned them as the evolutionary missing link between Europeans and Africans. The Irish would only go on to ‘earn’ their whiteness by opposing abolitionist movements and lynching black people, such as the 1863 New York City Draft Riots when Irish workers subject to the Civil War draft attacked their black colleagues, fearing they would steal their jobs. Otherized European migrants in the United States made a conscious decision to buy into the status of ‘white’. In doing so, they implicitly accepted the homogenisation and white-washing of their diverse ethnic origins as a means to attaining elevated social status and reaping the rewards which accompanied escaping ‘blackness’.

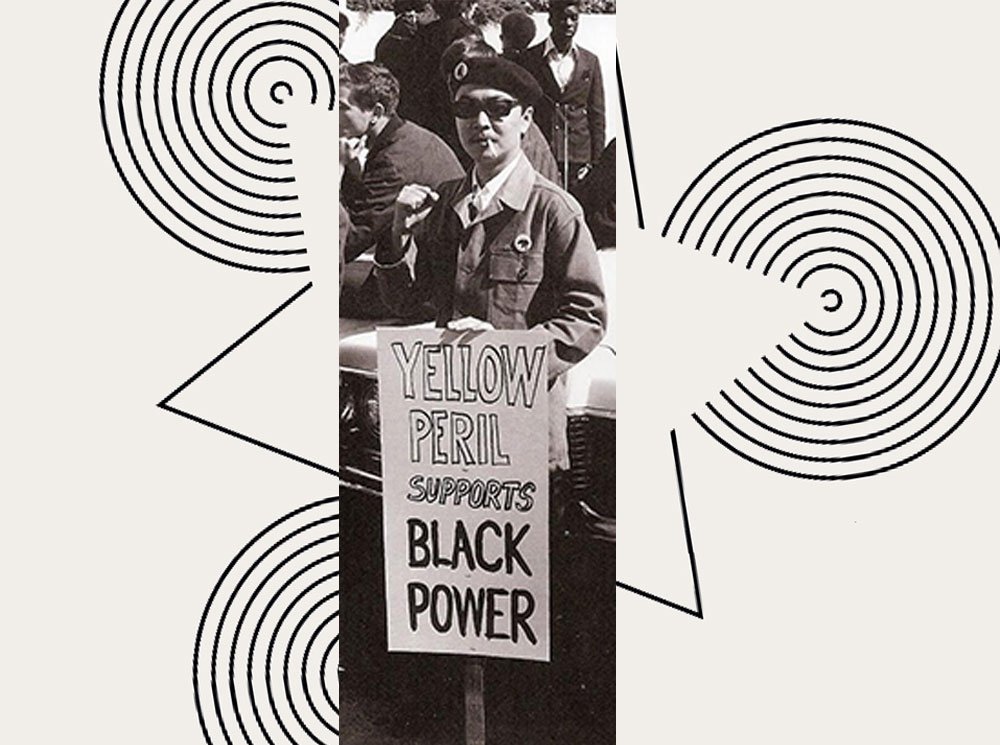

The definition of ‘Asian’ that currently dominates Western cultural imagination is similarly that of the model minority: meek, intelligent and dignified people who worked hard and sacrificed a lot to achieve the middle-class ‘American dream’. Social mobility of this kind often materialised at the expense of black people: for example, the formation of Asians’ model minority status between the 1940s and 1970s was in direct contrast to the demonisation of the Civil Rights movement. Professor Ellen D. Wu has demonstrated how Asian-Americans were defined negatively, primarily characterised by what they were not, whether this was white or black, at different intervals in history. We can trace a progression from when Asians were ostracised as the ‘yellow peril’, or ‘non-white’, during World War II, to when a postwar affinity towards Asian countries shifted their status to the comparatively positive ‘non-black’ category. With a shift in US foreign policy, Asian-Americans morphed from a horde of unhygienic, degenerate, opium-smoking railway and agricultural workers into a model minority. As the Black Power movement gained traction, their reputation as ‘well-behaved’, self-made migrants – a minority foil to black and Latino minorities – was only buttressed further.

But, as Professor Wu stresses to me in an interview, Asians were not just a tool for oppressive discourse. As in South Africa, they also actively participated in the rehabilitation of their public image from invasive to patriotic. In the long-run, it was a way of securing a place in the sun of postwar society; most immediately they sought to ensure that something like Japanese internment in the 1940s would never happen again. Japanese Americans used their participation in the US armed forces to show their loyalty; later, during the Cold War, Chinese Americans went to great lengths to prove that they harboured no sympathies for the victorious Chinese communists.

“Actually,” Wu tells me, “that foreignness is their key to acceptance. American leaders and thinkers – and Asian Americans themselves – start to see that it’s useful to have members of American society that supposedly have this natural affinity to Asia. They can become this mediating or brokering force to help the US firm up its relations with a really important part of the world in terms of national security.” So paradoxically, Asians gained acceptance precisely because of an inherent foreignness. The way they were conceptualised – predicated as it was upon a meticulous blend of inclusion and exclusion – was adopted into racial rhetoric and used to justify white disdain for black activists.

Of course, Asians never originally intended to advance themselves at the expense of black people. Racism reproduces itself beyond its historical conditions, sustained by the media and politics. Over time, the model minority myth has been supported by the Silicon Valley boom, where thousands of skilled immigrants from East and South Asia work for immensely successful tech companies as well as in a rich variety of other post-industrial sectors, most notably healthcare. Today, the Harvard lawsuit and Peter Liang protests have shown the skewed sense of self-preservation and entitlement in contemporary Asian-American activism. Such is the feeling of entitlement to social and political amenities that heightened class mobility has brought with it.

So could it be possible that, in a hundred years’ time, Asians would be considered fully white? To Wu, the only way this can happen is if nations such as the US stop pursuing geopolitical interests in Asia. Only then might Asians cease to be considered foreign bodies, in opposition to an all-American whiteness. “At heart,” Wu tells me, “whiteness is about an erasure of difference.” As long as the US sees itself in opposition to a nation, immigrants hailing from that region will never be true, homogeneous, apple-pie white citizens.

And what about darker-skinned Asians? In popular imagination, stereotypes of South Asians overlap greatly with those of East Asians, namely spiritual, accented, overachieving, emasculated men and servile women in need of white protection. But if East Asians can buy into whiteness, can South Asians do the same? According to the Pew Research Center, Indian Americans currently earn the most out of all Asian Americans with a median household income of USD $100,000 per year, providing class privileges that can help procure access to exclusive institutions such as the top universities. But no amount of wealth can erase the fact that race has always been constructed on ideas of difference. Wu points to the fact that we are still very much in the shadow of 9/11: “A new parallel to the yellow peril idea is the brown Muslim terrorist threat,” she says. “Certainly, if we can think of the group that is thought of as oppositional to Americans, I would say it’s the ‘Muslim terrorists’ or the so-called ‘illegal immigrants’, which usually means Mexican people.”

Until very recently, the US census’ definition of white was people whose origins were in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. It was only in February 2017 that the government proposed adding a specific category to identify Middle Easterners and North Africans as separate from white. Many Arab Americans feared that if they were to tick this new box instead of ‘white’ or ‘other’, the Census Bureau might pass on that information to the Trump administration. To them and to many observers, it is a phenomenon eerily reminiscent of Japanese Internment during WWII, when census data helped authorities to arrest people in their homes, and seize their properties for resale to white farmers. Just as groups like the Irish can evidently become incorporated into conceptions of whiteness, we must remember that other groups such as Arabs, Hispanics, and the Polish seem to be transitioning out of whiteness.

The idea of whiteness can be deconstructed and rejected: diasporic Asians can, and have in the past, cast their lot with other people of colour. The Vietnam War protests, widely recognised as seminal in crystallising pan-Asian-American identity, saw students across the world fervently oppose American neo-imperialism and identify with the suffering of civilians in East Asia. At the 1971 San Francisco Peace Rally, Patsy Chan delivered a rousing speech which still resonates today. She stated that: “the vicious imperialism which seeks to commit total genocide against the proud people of Indochina is the same imperialism which oppresses those of us here in the US by creating dehumanising conditions in our Asian communities, barrios, black ghettos and reservations.” The intersectionality that Chan agitated for directly catalysed the formation of the Third World Liberation Front, an organisation founded by black students which quickly formed coalitions with other students of colour. As a result of the TWLR’s direct action, university departments instituted African-American, Latino, and Asian-American Studies departments. The protests were successful primarily because they united people of colour with clear, specific aims and were successful in galvanising broader support amongst other progressive movements.

Some Chinese South Africans took a stand when they rejected the ‘white’ label, even when it would have put them on the winning side of Apartheid. But it’s not just Asians who need to fight against the cultural current that seeks to make us white – ‘white’ people themselves need to become conscious of the arbitrariness, instability and violence of the category. Constructions of whiteness may provide safety, comfort, and power, but they erase precious nuance in creating artificial, toxic homogeneity. We need to work towards a more effective idea of solidarity – one that seeks to dismantle those same structures which underpinned colonialism and are ever-present today. If we are to chisel away at the bedrock of racism, the mechanisms by which insidious conceptions of whiteness perpetuate themselves must first be destroyed. So let’s stop bickering over Harvard, and think about how we can build a more concrete, resilient and powerful activism for the future.

Words by Jiaqi Kang, Artwork by Jules Desai.