Remembering the Emo Music of the Midwest

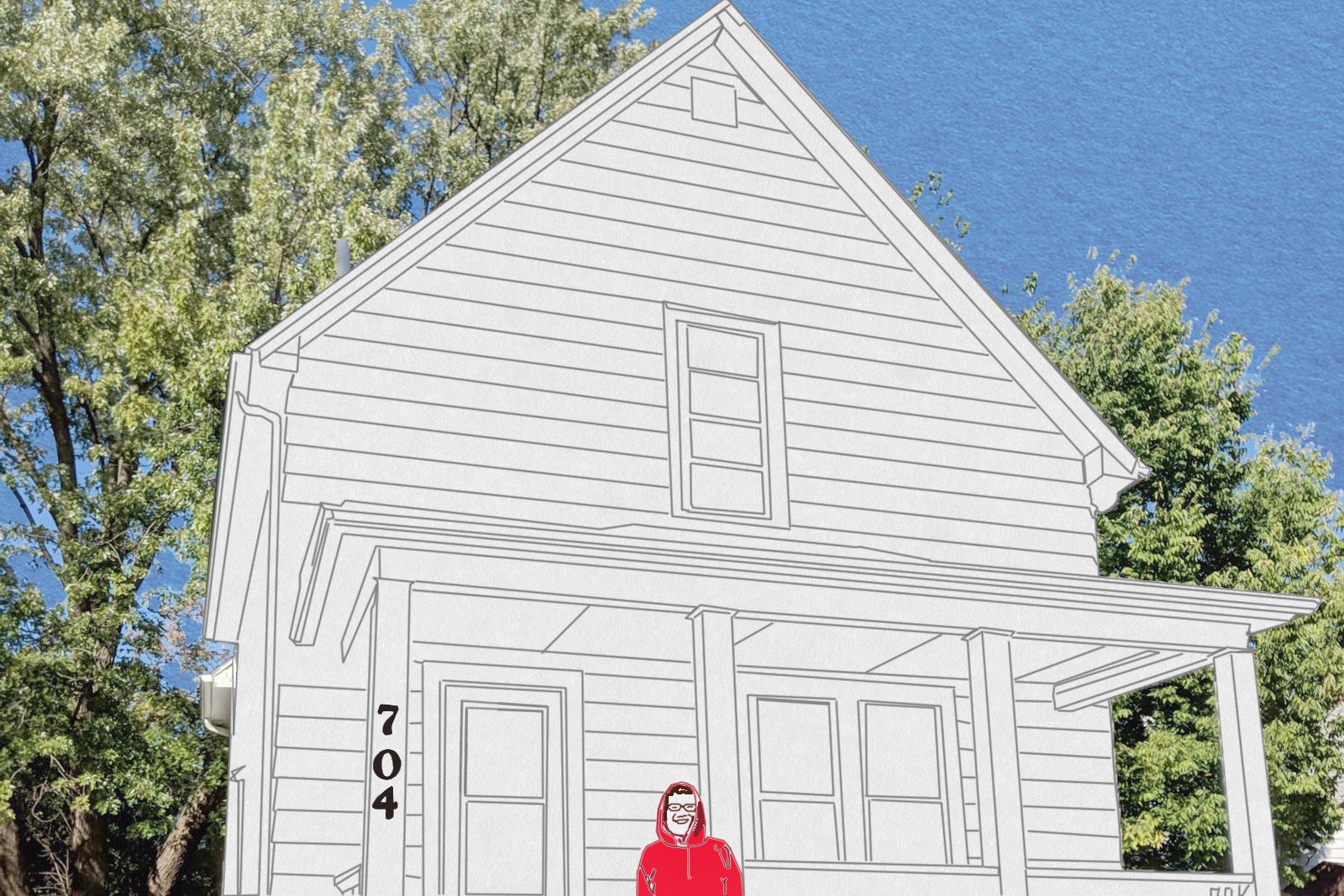

704 West High Street in the college town of Urbana, Illinois is no ordinary house. Lying in a leafy midwestern suburb, with weeds pushing through the sidewalk cracks and an overgrown front yard, a passerby could be forgiven for not looking twice at its bleached horizontal planks and single window. Just another house on campus, they’d think—if it weren’t for American Football.

American Football was a short-lived college band that played out of central Illinois in the late nineties. They released one self-titled album; it was recorded in a couple of days before the band left college and began their real lives. The album cover is a picture of 704 West High from below, taken late at night by a local photographer, Chris Strong, in 1999; a light, switched on in the upstairs room, turns the whole shot a shade of green you’ll only ever see in photographs.

A friend played me that album on a sunny afternoon in late May of 2018, looking out over the High Street. I didn’t like it at first; but the rising guitar riff, which opens the first song, took up a resilient seat in my memory. The music is a syncretic blend of emotional-hardcore, math-rock, and jazz; the lyrics were simple but sparsely confessional, words you’d say to a close friend, or a lover late at night. The album quickly found itself a place in the consciousness of the musical underground. Along with bands like Mineral, The Promise Ring, and Sunny Day Real Estate, emotional-hardcore—particularly played out of colleges in the dull midwest – came to evoke a certain place and time in rock music’s cultural history. Emo fans all over the world revere the way it sounds like a feeling, a sense of being too young to see the bigger picture but far too old to care. “Let’s just forget,” sings Mike Kinsella, American Football’s frontman, in “Never Meant”—“Everything we said. Everything we did.” His nonchalance is hollow; he doesn’t mean it, and he never did. The song is an act of remembrance, a farewell to a love he says means nothing.

Kinsella bids farewell to more than just an unnamed love. In, “But The Regrets Are Killing Me,” Kinsella’s lyrics, “these four years / and how we say goodbye to these four years / a long goodbye, with mixed emotions / just fragments of another life’ capture, for me, the indescribable way days drift imperceptibly into memory, the bittersweet sense of making an ending, of drawing a line. One day, everything – those houses, streets, spreading branches – will all look somehow otherworldly, seen first by someone else, the hero of another story.

I returned to the album in the summer vacation and for three months I didn’t listen to much that wasn’t emo from the mid to late nineties: American Football and Mineral, The Promise Ring and The Get Up Kids, bands defined by the fact of their sudden disappearance, by the clear sense of historical and personal place their music evokes. Despite all the pilgrims who make their way to 704 West High St, and crouch above the asphalt, looking up at the window and scratching into the road with chalk the place where Chris Strong took his photo 2 decades past, there is no going back in time. “The past is a foreign country,” wrote L.P. Hartley in The Go-Between (1953), one with closed borders, no room for travellers. I’ve never been to the Midwest and I never lived through the nineties, but listening to this music, for me, is nostalgia for a life I’ve never led.

But then, in 2014, Polyvinyl Records, American Football’s label, announced that, 15 years after dissolution, the band would return for two concerts, in New York and Champaign, Illinois. Mike Kinsella had gone solo and released 10 albums as “Owen.” Steve Lamos, the drummer, was a professor of English language. The guitarist, Steve Holmes, had settled down with a desk job in Chicago. They were grown-ups.

They sold out two nights in New York’s Webster Hall, where they played nine songs from their first album to crowds of people old enough to be their children. The songs are good and well-performed. But it’s hard to conceptualise the continuity between the men you’ll find on Youtube and the kids who sung about relationships crumbling and the end of a long summer. The cover from the second album is a shot taken inside 704 West High; light comes in from an open door, illuminating hardwood sideboards and a deep brown staircase. The second album is an excavation; they look behind the doorway to look for some past thing, some totem of a better time which they might find: but there is nothing. The album lacks all of the debut’s emotional presence, the inimitable way it sits with the listener, whispering in their ear. Cecilia Ahern wrote that “home isn’t a place but a feeling.” 704 West High Street represents the way some four kids felt at the cusp of life In a way, an attempt at reunion serves only to confirm mortality; American Football no longer sound like kids. Kinsella’s voice is hoarse, desperate, stretched by years of late-night gigs and cigarettes. 704 West High Street will never shine again with that ethereal midnight green.

The album, and the genre’s broader popularity, relies on its nostalgia, on its restless longing to live in the moment without ever really understanding what that means. The kids who were American Football knew that one day they’d look back wistfully at the unremarkable present. They struggled for something extraordinary in their quintessential town, and in the process, they made it – a cheap house, built quickly on the fringes of a college campus, and the music tied indelibly to its white-washed panels.∎

Words by Barney Pite. Illustration by Antonio Perricone.