Problematizing “Frida-Mania”

2am, 3am, 4am. Every single time slot was booked when the V&A opened its doors for a full 48-hour period during the last few days of the “Making Her Self Up” exhibition. Preceded by the 2017 Frida Kahlo show at The Dalí Museum, and followed by the largest ever retrospective of the artist’s work at The Brooklyn Museum this year, the V&A’s latest exhibition proves that we are living through a period of “Frida-Mania.”The trend for Frida Kahlo has long been in the making. Her face is on the cover of so many art history books, tote bags, and cigarette lighters that she rivals the Mona Lisa in tourist souvenir shops. She is surely the next “Picasso” of recognisable names in art history. While it is truly wonderful that the beloved Spanish Picasso is on the way to being replaced by a Mexican woman, popularity is always more complex than it first seems. In a turn of events that would make the artist herself shudder, “Frida Kahlo” has become a brand.

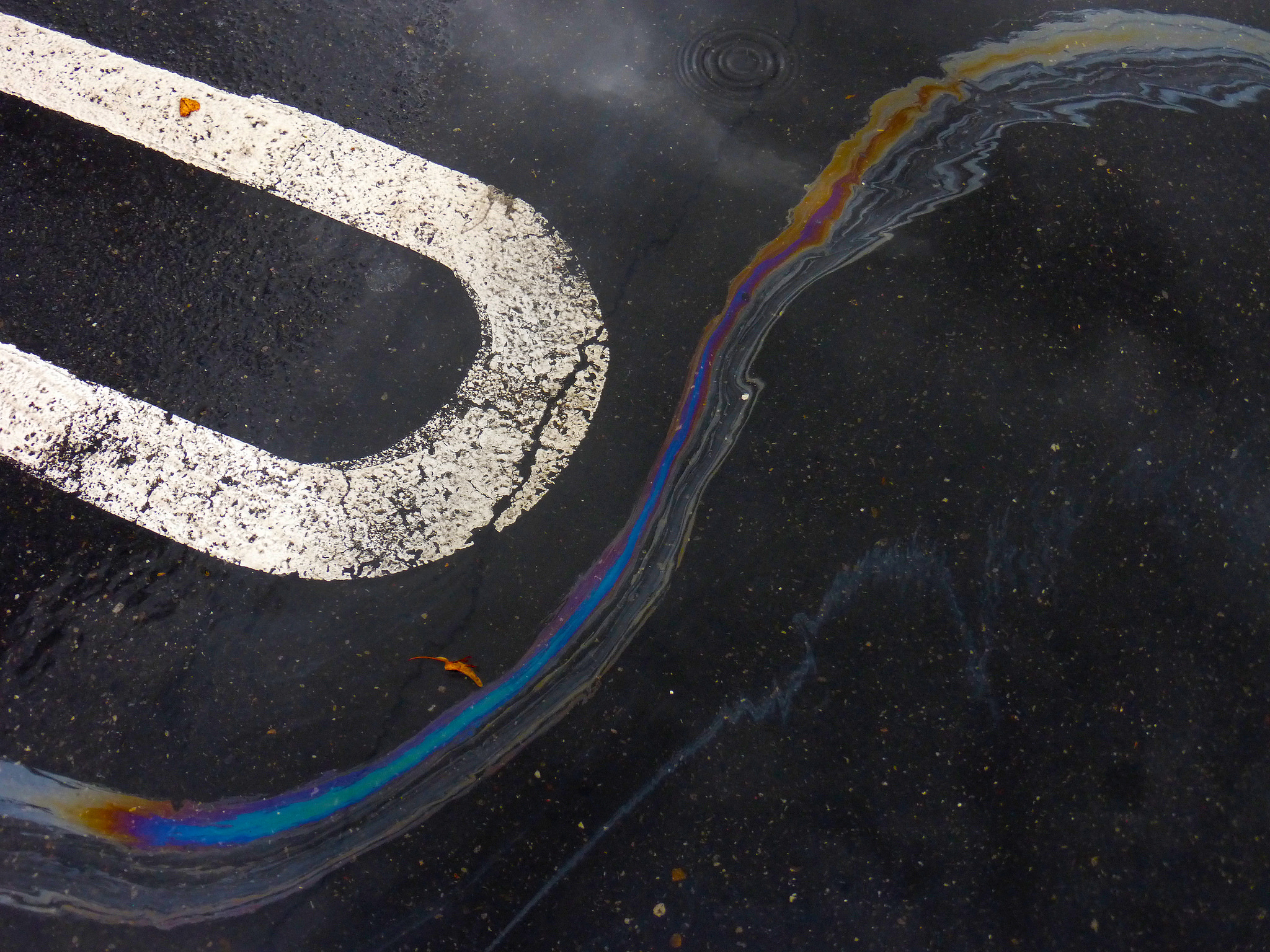

The Frida Kahlo brand sits uneasily alongside the artist’s commitment to Communism, which was outlined in the V&A’s exhibition. The first room showed a video of Kahlo and Trotsky in conversation from the late 1930s, when Trotsky fled Stalinist Russia to join the Mexican Communist Party. This section also contained one of Kahlo’s most famous paintings: Self Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and America (1932). An overt critique of American capitalism, the image shows Mexican soil being contaminated by industrial production lines.

Journalists, art historians, and Frida-fanatics alike have begun to cry that Kahlo would be horrified to see her face plastered on so much capitalist merchandise. As one of the most radical members of the Mexican Communist Party, it is ironic that her image decorated a £125 silk scarf in the gift shop of the V&A exhibition.

Through tributes like “Making Herself Up,” it becomes clear that—more than simply the commodification of a feminist, communist icon—the commodification of pain is an important force guiding “Frida-Mania.” It is well-known that Kahlo was disabled by polio as a child, and then suffered a traffic accident aged 18, causing lifelong medical problems. The treatment of Kahlo’s personal life reflects a trend in exhibition culture: as stories of suffering are so popular, narratives of trauma are repeatedly assigned to women artists, but cannot contribute to studies of their legacies without also playing a role in mythologizing, commodifying, even deifying them so their products bearing their images will sell.

A silk scarf, £125, created exclusively for the V&A and sold on the online shop, featuring a photograph by Leo Matiz in the garden wearing a Tehuana huipil and traditional skirt. /Credit V&A shop

The V&A exhibition traced Kahlo’s medical history in the room that followed the one where the Trotsky video played. The music was audible before I entered—quiet, electronic, and hypnotic. As if this wasn’t enough to lure me into a trance-like state, the lights were dark blue and purple. Staged as if it were a shrine, the atmosphere was prepped for extreme fetishization, which is exactly what I found. Glass cases were filled with Kahlo’s old belongings, arranged as in a shrine. Her paintings marginalised to the sidelines, objects that Kahlo had touched were showcased for the awe of an audience which dreams about her every movement obsessed. The most bizarre items were the used lipsticks, and the most disturbing were the empty medicine bottles. Crumpled medical records about her miscarriages and empty pharmaceutical packets were displayed as anthropological objects.

Kahlo was open about her medical trauma in her paintings, which could justify the display of the medical records. You could even explain the spectacle of the used lipstick by saying that Kahlo was proud of her self-image, and therefore it makes sense to display her tools. It is certainly radical to exhibit a disabled body in an age where able-ism is pervasive, especially in art galleries—indeed, Kahlo’s communist corsets and red dragon prosthetic leg were highlights of the exhibition. But perhaps the trance-like music and glass cases of the V&A exhibition made the fixation on her medicated body appear more fetishistic than celebratory.

The V&A justified their fixation upon Kahlo’s image in their exhibition by arguing that “Kahlo dressed up even when she did not expect visitors, and even when confined to bed. The Casa Azul contained many mirrors, and friends recalled her ritual of choosing skirt, blouse and shawl […] Kahlo’s mirrored reflection was an affirmation of the care with which she composed her appearance, and an assertion of her identity.”

This is a compelling explanation that helps rationalise our obsession with Kahlo’s body—she, too, was “obsessed”—and so justifies our compulsion to buy a pillow with her face on it over a print of one of her paintings. But there is something more insidious going on.

Being a successful woman artist, especially outside of white Anglo-America, requires not only selling successful paintings, but also selling an attractive image of the artist herself. Despite their liberated role as painters, rather than models, women artists have not been able to entirely shake their status as art historical muses. Even with a paintbrush in hand, their face and body are still gazed upon as if they were nudes on a canvas.

Moreover, we should think more critically about the popularity of pain. Specifically, we should consider whose trauma is deemed marketable as an overwhelmingly key part of their legacy. I have never seen Picasso’s medical records, despite the fact that his paintings often dealt with the subject of venereal disease. I have never seen Salvador Dalí’s psychiatric papers in glass cases, despite his open interest in psychology. Who is a creatively eccentric genius, and who is a traumatised patient? Perhaps nothing explains the genius of a woman artist more persuasively than unusual suffering—Kahlo validates both the “tortured artist” trope and the peculiarity of a successful woman.

Yet for all our cultural obsession with female pain in exhibitions, films, music videos, and more, runs contrary to our social dismissal of women’s pain in hospitals. A seminal 2001 study by researchers at Maryland University, titled “The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias Against Women in the Treatment of Pain,” determined that self-reports of pain by women patients are treated much less aggressively than self-reports by men. These sorts of paradoxes are typical of human contradiction. Just as pornography prevailed in the sexually repressive Victorian era, twenty-first century women’s trauma is glamorised despite the fact that we live in a society that denies women’s pain.

Many of the most recognisable women’s names in surrealist art are the names of women who have shared their trauma—for example, Leonora Carrington, famously admitted to a mental asylum; or Dorothea Tanning, who is the subject of articles such as the recent Hyperallergic piece: “Dorothea Tanning’s Surrealist Depictions of Women’s Pain.”

If not trauma, the next ingredient in the recipe for fame for women surrealists is affairs with recognizable men. Kahlo’s relationships with Leon Trotsky and Diego Rivera have proved fruitful for this formula. Another prolific surrealist, Lee Miller, was the subject of a 2015 exhibition at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Titled “Lee Miller and Picasso,” the Guardian reported that the “new art show reveals chemistry between Picasso and Lee Miller.” In the same year, a work of historical fiction, The Woman in the Photograph, by Dana Gynther, elucidated Miller’s affair with Man Ray.

One current exhibition at the New York Museum of Sex, titled Leonor Fini: Theatre of Desire, 1930-1990, challenges these conventional narratives of surrealist women’s traumatised lives, loves, and bodies. In presenting Fini’s erotic paintings of female pleasure, rather than pain, the exhibition has escaped the mainstream storyline of national galleries, and does not succumb to the easy rewards of selling the relationship between pain and popularity for dramatic effect.

Many artists are becoming increasingly sceptical about the political potential of “trauma narratives.” As contemporary artist Travis Alabanza explained on their U.S. tour of 2018, a world in which trans artists are only given a platform, exhibition, or credentials when they are talking about pain and suffering is a world in which we are perpetuating the same story over and over again, all the while believing that we are really changing the game.

Similarly, bell hooks’ essay, aptly titled “Moving Beyond Pain,” criticises Beyoncé’s Lemonade for its fetishisation of black female suffering, as “much of the album stays within a conventional stereotypical framework, where the black woman is always a victim.” Moreover, “it’s all about the body, and the body as commodity. This is certainly not radical or revolutionary.” Both Alabanza and hooks point out that marginalised groups, in particular, women of colour and gender-non-conforming people, are vulnerable to the commodification of trauma all too easily sold as a digestible narrative. It is perhaps this danger that makes Frida-Mania sit so uncomfortably in the history of art.

I would replace the crumpled medical papers in the glass cases of the V&A exhibition with Frida Kahlo tote bags, Frida Kahlo t-shirts, and Frida Kahlo coffee cups. Perhaps that would encourage us to think more critically about our commodification of women and more carefully about our fetishisation of trauma. Both are products of society’s “brand-ification” of pretty much everything. That alternative glass case, surely, would be more thought-provoking than a used lipstick. ∎

Words by Monica Lindsay-Perez.