Investigations

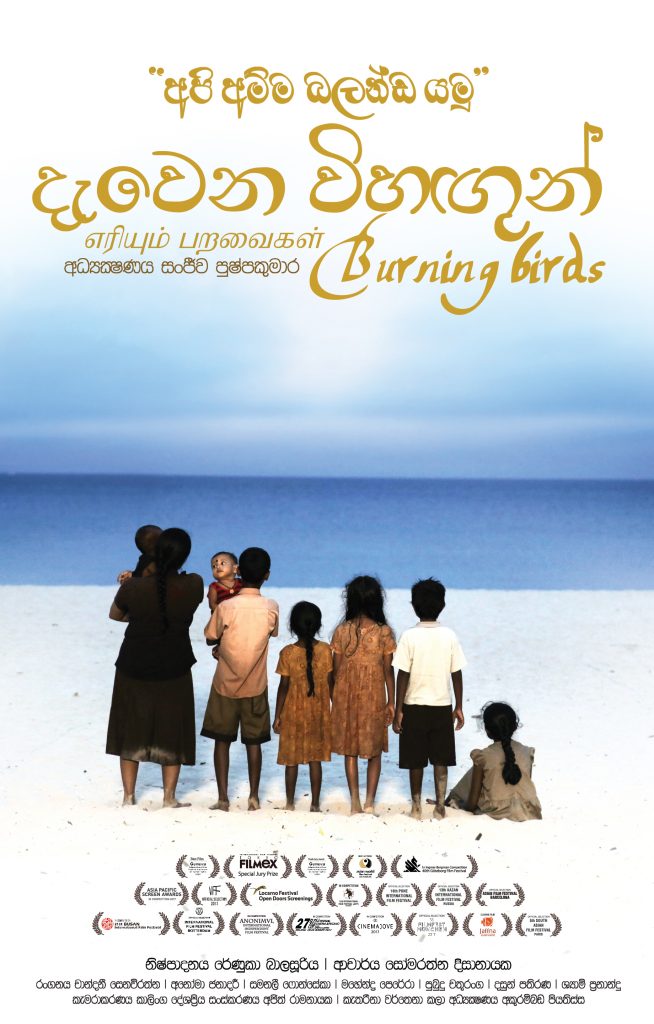

A background throb of birds and insects. Then the quiet chanting, tinny and dampened as if playing through a radio. Then the gentle scraping and clacking of tea being made as the black title screen fades to a beautiful palette of browns, and we first see Kusum.

My second viewing of Burning Birds feels like an eerie deja vu. I first watched it in Colombo, Sri Lanka, in July. This time, it is November, and I am in Harrow, London, but the situation is remarkably similar: a large, 1930s Art Deco cinema, with a kind of faded, nostalgic beauty. A small but engrossed, mostly Sinhalese audience sharing both the huge auditorium and the emotional journey of the film with me (there are audible gasps at climactic points). There was something magical about being able to step back into this space.

After the first screening, I set out to find more about the arthouse film scene of Sri Lanka – a topic that seems so pretentiously niche to many Brits back home that it continues to raise eyebrows in conversation. But it’s not something I’ve ever regretted pursuing. By the time I watched Burning Birds again in Harrow, I’d seen many other brilliant films normally left confined to the film festival bubble, engaged in conversations with two of the country’s most prestigious and interesting directors, and even spoken to the Sri Lankan Prime Minister.

These directors are Vimukthi Jayasundara and Sanjeewa Pushpakumara. Both gained recognition withvia powerful, aesthetically beautiful debuts about the Sri Lankan Civil War that side-step both direct partisanship as well as the white-washed government narrative. Jayasundara’s Sulanga Enu Pinisa [The Forsaken Land] won him the Caméra d’Or at Cannes in 2005, and Pushpakumara’s Igillena Maluwo [Flying Fish] won accolades around the globe in 2011. Davena Vihagun, or ‘Burning Birds’, is Pushpakumara’s second film.

But despite acclaim on the festival circuit, the response to these films was not universally positive. In particular, both received governmental backlash in Sri Lanka. In 2005, shortly after The Forsaken Land won the Caméra d’Or, Rear Admiral Sarath Weerasekera held a meeting with film directors, and declared in a public comment piece that they should be making pro-military films. If a film “even indirectly” gave support to any objectives of the Tamil Tigers, he said “it amounts to treason and should be dealt with severely”. Jayasundara and his producers and actors started receiving threats and they withdrew the film after two weeks. At the time Jayasundara stated that “Artists and filmmakers in Sri Lanka don’t need any government or military supervisory body to tell them what to do…If the military wants propaganda war films then it should start its own production company. I’m sure there are people who would be quite willing to help them”. It seems there were not so many: after retiring from the Navy, Weerasekera went on to direct his own propagandistic war-film in 2011.

Although the Civil War officially ended in 2009, the fallout of Pushpakumara’s Flying Fish demonstrated the seriousness of the military’s threats to directors. An anthology film in both Sinhalese and Tamil, set during the war, the government claimed that the film insulted the military. It was banned, and an entire film festival was cancelled in 2013 to prevent its screening, with a criminal investigation following shortly after.

In the past half-decade, it seems this situation has improved slightly. “Things have changed since the last government”, Jayasundara tells me, “and they are now quite open”. I ask Pushpakumara if he feels similarly and he says that “compared to all the previous governments, the Public Performance [censorship] Board is making progress I think”. But this comes with some caveats. Firstly, Pushpakumara is quick to point out that political climates are ephemeral: “It can be changed at any minute”. This was demonstrated very clearly at the end of 2018 when President Sirisena removed Prime Minister Wrickremesinghe from office and replaced him with ex-president and ex-political foe, Mahinda Rajapaksa. The resulting constitutional crisis lasted two months before Wrickremesinghe was re-appointed, but demonstrates the political instability of the country.

But even aside from politics, Pushpakumara says “there are different kinds of censorship. For example, theatre owners. They don’t like to screen some kinds of films, such as mine. It’s not the government, but it’s a different kind of censor board I feel”. In part, Pushpakumara suggests that this is due to theatre owners still having political connections with the previous regime, making them “very careful not to show films questioning what happened in the [recent] history of this country”.

But it’s also a broader cultural challenge: not all Sri Lankan audiences are ready for gruelling, sexually and violently explicit viewing, and cinemas aren’t going to take economic risks with screening. “I’m not completely ok with what I’ve achieved audience wise in Sri Lanka”, Jayasundara tells me. “I always feel like it’s not accessible enough to Sri Lankans. In my films there’s a lot of nudity, sex scenes, quite controversial elements. Some people get really offended because it’s not very easy for them to watch. It’s complicated for them to understand in comparison to other Sri Lankan films.”

Jayasundara had particular difficulties with an Indian Bengali film he directed, Chatrak [Mushrooms], for featuring a no-body-double cunnilingus scene. He’s probably right in saying that “In Europe there’s no problem, people are used to seeing this”, but that doesn’t mean his films seem tame or lack shock value – Sulanga gini aran [Dark in the White Light] comes to mind in particular. While perhaps the sex scenes are not quite as explicit as the one in Mushrooms, the context made them much more shocking to me. The main character is a terrifying surgeon who smells his bloody fingers after surgeries and rapes comatose patients by night, scenes interspersed with a Sinhalese Buddhist monk musing about death.

A large part of the reason that more graphic cinema is not yet culturally acceptable might simply be that people lack exposure to it – it must be screened a certain amount before it crosses the threshold into normalisation. In the latter ‘70s and early ‘80s there was an explosion of low-budget, domestically produced cinema in Sri Lanka. In 1982 there were so many films being made that there was a waiting list of 5 years for their cinematic release. But with the socialist politics of the early ‘70s giving way to a more capitalist government, and then the beginning of the War in 1983, cinema attendance started to fall by the tens of millions and increasingly fewer domestic films sought to present ‘real life’, giving way to a genre of film more stylistically similar to Bollywood: musical, large sets, often nationalistic, epic, pseudo-historical plotlines. After nearly half of Sri Lanka’s cinemas closing in the noughties, this is now the dominant style of film screened around the country.

This is not to say that there is not still a thriving arthouse scene, but it faces challenges. As Pushpakumara tells me, “there’s a huge divide…two different cinema. If the story is more patriotic, and exaggerates very much about the Sinhala Buddhist mindset and history, these films find money. But most of these films, 99% are [artistically] very low quality. It’s not cinema at all. But those films make money and I don’t know why, maybe that’s the Sinhala Buddhist ideology at work. Arthouse filmmakers have no chance to find money in Sri Lanka. Most of them, for example myself, are depending on mostly foreign funding. We are suffering. Even my films; Flying Fish still hasn’t been screened in Sri Lanka, Burning Birds didn’t have a proper theatrical release. Only a few theatres screened the film.”

This is true for foreign cinema screened in Sri Lanka too – the only films screened are the largest budget ones from India and America. According to Jayasundara, “It is more commercial films these days. It’s very hard to see a film from the UK in Sri Lankan theatre for example. You are not able to see all American films – only Hollywood. There are so many interesting American films being made but it is very difficult to see them.” Of course, this could be said of many countries – it is hard to see Sri Lankan cinema in England. Jayasundara points out that the internet is serving as a democratising force in some ways – “things like Netflix are opening up and it’s not so difficult to find a movie these days. If you are able to trace online you may be able to get it. But it’s not coming as regular cinema.”

I mention this idea to Pushpakumara and he agrees, but emphasises “but it is not the cinema you know. You are able to get the content, even the message [when watching online], but not that cinematic experience. It is two different things.”

And why is it that the audience atmosphere in both screenings I saw of Burning Birds was so intense? Why are other trips to the cinema not like this? Jayasundara was introduced to film through going to see Bollywood movies with his mother in Colombo as a child, but he doesn’t find them engaging. The commercial Bollywood-esque film, he says, “is created for the sake of creating it and it just gives you a total fairy-tale. There’s no reference to reality. There’s no way you can associate that into your life whatsoever.

“In Bollywood you’ll see that most films are shot outside of India. Lots is in the west, e.g. in Switzerland. That’s disturbed me because why can’t the same story happen in India? People don’t want to see their own harsh realities. The psychological landscape of India probably is more dreamy, that’s what Bollywood is able to deliver. Not what is really happening but something that is a total fiction, totally created.”

I pick him up on this – films such as Mushrooms are surely very much a psychological dreamscape, rather than ‘realism’? It moves slowly, often without dialogue, opening with a long sequence about a madman playing in the trees with a soldier. It also contains an actual fairy-tale being told towards the end – where is the division between this and the films being criticised?

“I’m interested with interactive stuff, like when you’re playing a game. You know that you’re playing a game. That’s fine, as long as you know. But if you’re no longer saying that you’re playing then that’s really sad for me.” Jayasundara also creates video installations for art exhibits, something he says feeds back into his cinematic work. “You can go into someone else’s head and experience something crazy or weird or funny or sexual or whatever and it doesn’t matter – that’s fine but at least some reference to your own life and it will have some impact.”

And regarding the fairy-tale in Mushrooms, he explains that it is different; “A story within another story. Something within. I like that feeling”. Myths and fairy-tales are “alive” he says, and have been for thousands of years. “Why are people still telling these stories? What are their original forms? I don’t want to kill that by making it into the film but I want to keep them in my story. It gives another perception of something…you cannot act out these stories but you can create reference to them.”

Pushpakumara too tries to blend an abstract surrealism with stories that are grounded in reality (“That’s what I like actually”). For him, this grounding is particularly personal. I asked why his short films from the noughties, as well as Flying Fish, all focused on soldiers:

“I was born and grew up in a very small and remote village in Eastern Sri Lanka. I grew up with army soldiers; during my childhood I spent most of my time when not at school inside army camps. The school teachers would often ask us, ‘whom do you want to be in the future?’, and I can remember that every time I said ‘I want to be an army soldier’. They’d ask why and I said, ‘so I can safeguard my country and my people’. We’d go to military camps during the day and night. For example, I can remember the first time I watched Robin Hood, the TV series. So it’s 1986-8 I guess, it’s telecast every Saturday, and at 6.55pm, wherever I was, I’d be running with my brother to watch Robin Hood at the military camp. One of the first films I see in my life is ‘Commando’, the Arnold Schwarzenegger film. I watched that film inside the army camp with the army soldiers.

“So I’ve fallen in love with the army, then when I grew up they beat me and beat my father several times without reason. For their own enjoyment. And I realised when time passed; army soldiers are human beings, of course, but they are instrumentalising some kind of authority. I realised that authority is the state. The army’s not just human beings, it is apparatus of the government. So that’s my connection with the army.”

After the backlash to Flying Fish, Burning Birds is a film without a single soldier in – but it still draws from autobiography – “Burning Birds is also inspired by my own life, and my own family. 1989 [the year in which it’s set] is a very important year. Burning Birds focuses on a mother, 37 years old, with 8 kids in the family, when the father was murdered. I also lost my father when I was 11 years old and we were 8 kids in the family, my mother was very young, 37 years old. So I started the film from this, my very own experience. 1989 is the year that there was a huge Marxist insurgency and we lost more than 60,000 young lives through the country. Mostly Sinhalese young people. So I was noticing these things happening around my neighbourhood, my hometown. I take this personal experience onto a huge social-political canvas.”

And yet there is still a notable absence of specific reference to the war for a film with this premise. Both directors cite Tarkovsky as an influence, and Jayasundara has mentioned before how he admires Ivan’s Childhood, and Stalker, for their ability to address war psychologically without featuring battles and the usual mechanics of war cinema. The Forsaken Land, which is set during the 2002 ceasefire, as well as Flying Fish and Burning Birds can be seen as following this format. But a lot goes unsaid in a literal sense in these films; dialogue in Mushrooms or Burning Birds is sparse and secondary to visuals and soundscape. I hesitate to categorise (Jayasundara says “all this classification for me is very reductive”), but these films could easily be classed under the banner of ‘contemporary contemplative cinema’. Slow moving, with a focus on long takes, and a flirtation with minimalism.

“I like the feeling of suspended silence”, says Jayasundara, “when the image really speaks. I like that. I like when cinema is able to do that without talking”. Pushpakumara echoes him when I broach the topic; “Another thing about the dialogue, I can say this: these people [in Burning Birds] are very much wounded, and beaten. When you are very hurt you are not able to speak. I thought the images would speak a lot more than the words. Therefore I thought it better to show things rather than tell. In this case I learned a lot from Tarkovsky, and I learned from Robert Bresson and of course Ozu, Kurosawa, Hou Hsiao-Hsien of Taiwan. These filmmakers taught me a lot how we can work with little words.”

But this approach also gives a film opportunity to be understood by an audience unfamiliar with detailed events of a particular time or place – Burning Birds absolutely is about Sri Lanka in 1989, but the message conveyed is broader, and one needn’t be familiar with the Marxist insurgency and death toll that Pushpakumara references for the film to have impact. Jayasundara is particularly drawn to the idea of cinema being escapist: “when you’re in the movie theatre watching a film, you’re in that universe. When I watch a film, let’s say an English film, maybe the language, the landscape, it only matters to me for a few minutes and then I’m convinced that I’m already in the film. I’m dealing with my own emotions afterwards. Cinema should be the place where anybody can just enter and live in.” When I ask Pushpakumara if he has a target audience he says “I’m conscious that it’s not possible for my films to reach all people but mainly the people that love cinema. That’s my audience.”

This appeal to universality is notable, for both men describe working in a field in which they are constantly labelled as representing different parts of the world, making cinema that represents one country or its interests. In Sri Lanka, Pushpakumara tells me that “the main accusation that they are using against my films and me is that I’m doing a kind of thing that Europeans want to see. That I make that film because that’s how Europeans see Sri Lanka. But I don’t think so,” (at which point he laughs over the phone) “I make films that I want to make, not what Europeans want! Because I don’t know what Europeans want! I’m not worrying about that.”

On the flip side, Jayasundara expresses frustration at always being renegaded in Europe under a tokenistic label of ‘Asian’ or ‘Sri Lankan’ film. “lots of these international film festivals are really having this naming/tagging, saying that ‘this is from here or there’…I’m really disappointed with that. I know that many people, even myself, [ask] how do I represent Sri Lanka? What does that mean? How can any person represent a country? You are an individual. There’s no way you can represent a country. If you look at me from a distance, of course [in relation to] everything about me you can say I’m a Sri Lankan, anything in my films you can call Sri Lankan; but that’s not my purpose. If anybody wants to categorise and say I’m a Sri Lankan filmmaker I’m not going to say it’s not true. As a matter of fact it is. But that’s not my work.”

This conversation leaves me feeling guilty – in grouping these directors’ interviews together in an article supposedly about Sri Lankan cinema rather than just featuring them as individuals I am a perfect example of what we’re discussing. But while I never intended to write an article ‘othering’ these filmmakers it is a reality that Sri Lankan cinema is totally unfamiliar to UK audiences. All of these issues arise in part from an economic imbalance within the industries: figures such as Jayasundara and Pushpakumara are forced to study at film schools outside of Sri Lanka, and rely on foreign countries for funding, screening, and distribution because there is no domestic money being offered. That means that there are fewer Sri Lankan films than French being made for example, marginalising them, it means that Sri Lanka never builds enough of an infrastructure for its filmmakers to promote their own films internationally, and that domestically these filmmakers are seen as ‘too European’.

In October Prime Minister Ranil Wrickremesinghe gave a speech at the Oxford Union, and I decided to ask him about how to address these issues. After referring to Jayasundara and Pushpakumara for pointers I asked him why his government was so hostile to the film industry. Why it has no national policy on cinema, despite proposals having been given to him. Why he revoked the tax benefits for filmmakers that previous governments implemented, and why there’s no funding for arthouse film or for the creation of a film school despite demand. Why the government hadn’t stepped in to fund the successful but short-lived Colombo International Film Festival – since Japanese funding for it had been cut, Pushpakumara told me that Sri Lanka is now the only country in South Asia bar Maldives not to have an international film festival.

When I finished there was an uncomfortable tension in the air; everyone’s faces (including Wrickremesinghe’s) betrayed a disbelief that I would use precious Union time to ask about arthouse film while the chanting of Tamil protesters filled the debating chamber. After a few moments he asked me to repeat what I’d asked, an interaction so bathetic and awkward that it was edited out of the youtube video. The audience’s facial disbelief may well have been justified: obviously underfunding a film industry could never be compared in importance to the persecution and still continuing ethnic war-crimes of the Sri Lankan government against Sri Lankan Tamils. But reflecting on my conversations with Pushpakumara and Jayasundara I am struck by the fact that while in some ways incomparable, these separate actions are not unconnected. Censoring and discouraging the arts is clearly linked to authoritarianism, the actions of a government that for all its finger-pointing at Tamils, has not itself yet left behind the unforgivable behaviour of wartime.

Wrickremesinghe’s reply in the end was a bit of a non-answer, and he chose only to address the latter point about festivals: “We’ve had some film festivals in Sri Lanka, but there’s a tussle between some of the local producers who want to protect their market and the rest who want to open out. So that’s an ongoing battle in Sri Lanka. We’ve had some film festivals, the latest ones have been local, on the late Lester James Peiris, who passed away just a few months ago. We’ve had festivals around him. But there is a case for more film festivals in Sri Lanka and I’m all for it, but I don’t think my sentiments are shared by some in the industry.”

I am optimistic that the day will come when Sri Lanka has a film school, and an international and domestic industry that supports challenging dramas as well as commercial entertainment. But until then, life will go on and Jayasundara and Pushpakumara will stay busy: the former has just collaborated with two other acclaimed directors, Prasanna Vithanage and Asoka Handagama, to create Thundenek, also marketed as Her. Him. The Other, an anthology film in Sinhalese about a pro-LTTE videographer, a Sinhala teacher and a Tamil mother. Pushpakumara is working on multiple films; including one about Sinhalese and Tamil mothers forming a ‘mother front’ together against wartime disappearances, and one about Leonard Woolf, husband of Virginia, who spent time in Sri Lanka at the beginning of the 20th Century. Pushpakumara describes him as a “very controversial and very complex character. On one hand he is a very tough and strong and cynical colonial ruler. At the same time, while he was executing all the rules of colonialism, he was questioning it. He was a man with a split mind.”

And younger generations in Sri Lanka who’ve grown up in relative-peacetime might present a more accepting future audience: Jayasundara thinks that the internet and social media is normalising old cultural stigmas, and Pushpakumara has been touring universities with screenings of Burning Birds, discussing the film and progressive politics with students after, whom he describes as being very receptive to all of these things.

How to describe an ending without spoilers? A bloodied face waits silently for the flames to engulf the old structure and make way for the new. The sun sets slowly and the red flames fade to black, their crackling being replaced by strings and a young voice singing.

The international cut of Burning Birds was different. It contained scenes that weren’t screened in Colombo; of violent rapes, prostitution, nudity. In the toilet, that liminal space between the cinematic experience of Pushpakumara’s “psychological landscape” and the street outside Harrow Safari Cinema, I ask a man washing his hands if he enjoyed the film. He looks at me very weirdly, and nods, before rushing out.∎

Words by Bertie Harrison-Broninski, Artwork by Tara Kelly, All images courtesy of Vimukthi Jayasundara and Sanjeewa Pushpakumara