Short Fiction

by Altair Brandon-Salmon | February 11, 2019

The stone path stretched away around the sun-bleached rocks and out of sight. Scanning her eyes further up towards the Cloud Rock of La Cumbre, she could spy grey horizontal streaks and bobbing pips along the oblique route to Roque Nublo, betraying walkers making their slow journey. It was the symbolic centre of Gran Canaria, and from the cabildo, it looked like a thick red finger pointing up towards the celestial sky, once revered by the native Guanches. The Roque was a volcanic chimney, formed from archaic geological pressures and carved over the centuries by the dry, sweeping winds.

The sun’s rays were a waspish sting in the thin air. The barren landscape relinquished little shade, the soil bitter and loose. The only water to be seen was the Atlantic itself, a hazy livid blue to the west, merging with the horizon.

The woman was dressed in khaki shirt and shorts, Panama hat and cracked boots, all faded with dust. The face was creased by black lines and splintered lips; only her watery-grey eyes showed life. She stood apart from the Spanish, her beaten skin lacking the supple olive-bronze of their colt-like bodies, darting up the route in clumsy flip-flops, muscles bouncing loosely under thin vests.

She was a woman alone, striding forward along the path in a rapid march, briskly overtaking the other walkers, while looking out to the left, out at the vast, variegated landscape, full of deep canyons and chiselled rocks. The shadows cast downwards by the rough silhouettes of the peaks were dark indigo, creating sharp distinctions between light and shade. It seemed a pre-historic country, yet only half a millennium before there had been flowing rivers, dried up from the destruction of the island’s forests by the Spanish conquistadors. So not what the Guanches saw, she thought.

Her legs felt strong, no build-up of lactic acid yet, and her body was calm under the strain, limbs flowing through the air like a dancer as the ground started its upward ascent. The first beads of sweat trickled down the back of her neck.

The woman remembered how differently her childhood walks had been, through the green lands of Wessex and the journeys up to the mist-enshrouded Lake District, lorded over by the Old Man of Coniston. Two islands located in the Atlantic, but their geography and topology were as different as the girl to the woman.

The hewn-out steps curved round the path and she brushed against sharp flowers, short and cropped amongst the cacti, grudgingly beautiful. Below, down the steep cliff face, she could see a grey, circling hawk, gliding with an easy grace, casting a black shadow beneath. Here was a creature wholly part of its environment, lacking the awkwardness of the white-flowered brushes, growing out of the craggy ledges. It was right that only a predator could assimilate into La Cumbre. The memory of what her brother had once said—‘You’re truly high up when you look down on the falcons,’—shot through her mind, but she suppressed it.

As the path’s ascent slowed, a small group of tourists, speaking rapidly in German, blocked the way ahead, walking at a measured pace with branded walking sticks. She brusquely mounted the low rocks to the right and cut past them; a rise in their tone of voice might’ve been a reprimand, might not.

The track had gone over a rocky ridge and come down on the other side; she was lithely dashing over uneven formations of rocks. There were brittle pine trees here, the short needles giving shadowy relief. She was sweating profusely, her shorts chafing her thighs, becoming conscious of the exertion properly for the first time. She’d expected this, of course. Anyone walking only a few degrees above the equator had to be prepared for a deep burn in the gut.

As she gambolled up the incline, the rocks narrowed, and she had to lift up her arms to avoid scratching them on the thin, prickly cactus spikes on either side. They formed a tapering corridor that burst out onto the plateau. It was wide, much wider than she’d expected—a flat expanse of rock leading up to the distant Roque.

Her face grimaced in the painful light, her eyes pursed in to thin lines like the shallow faults running across the stone floor. Across here the Guanches had come to enact sacred rituals, but her only focus was on the deep, searching breaths convulsing her body. There was a steady ach in her legs; further back, it’d been dull, muffled like an echo in a cork-lined room, but now it was the roar of the sea.

She consciously quickened her pace, but soon relapsed into her older rhythm. She had to talk herself around the effort, promising a long drink as soon as she touched that rock, so large now in her vision… Damn, this plateau’s long.

Suddenly, as Roque Nublo filled her vision, the ground dropped away, to reveal a crevice of rocks. It sent a deadly, raking tremor through her body, a soft blow of lead to the gut.

The woman stumbled forwards. She ignored any smoother route to the right, over boulders and rocks, and instead slid down the gully, past tall, thorny bushes and pulled herself up the other side, gashing her knees, but there was only one thought in her mind now. To caress the great stone wall.

She sailed past the shoals of tourists and almost fell against the Roque, her hands tracing out the shallow relief of chiselled and scarred rocks. It was a wild moment, scouring the stone with her dry fingers sheathed in a film of dust.

The woman took her water bottle and allowed a mouthful of water to quench the itch of thirst. Out across the stone plain were clumps of polychromatic people, dotted like exotic, dried-out weeds in the white light. They didn’t see her and she no longer saw them, either. Her breathing was thunderous, her heart a copper bell ringing a high-pitched shrill. She concentrated in taking slow breaths through flaring nostrils.

Already the woman’s inner strength was ebbing back, and she followed the ledge around the Roque. On the other side, the plateau ended abruptly. It angled downwards before being abbreviated by a sheer drop, falling away to the canyons and hillocks of the land. Only a small, thin ledge extended outwards, a bridge into the vast, dominating sky. A crook in the rocks split the bridge like a dagger.

She crawled round into a hollow carved into the Roque by the Guanches for their religious ceremonies. They had thought this was the roof of the world, the Roque an intermediary between the blue abyss above and the soiled earth below.

Today though, the site was inhabited by young and jocular Spaniards, dressed casually and easily, laughing and talking with an effortless, musical timbre. Out on the spit of rock, two of them were balancing precariously, their thin arms swooping through the air in exaggerated motions of stability. A woman, her dark hair matched by her oval sunglasses, shrieked as the man behind her mockingly pretended to push her. Their friends looked on, aiming cameras at the pair.

The woman wondered if anyone had ever scaled Roque Nublo, completed humanity’s conquest of Gran Canaria by standing aloft its icon. It was a precipitous face that would require a finely-skilled climber. In her youth, she’d dabbled in such things and knew the preparations necessary before attempting it. Yet she would never do it. You’ve got to know your limitations, she thought, otherwise you’re not worth a goddamn.

The spit was clear now, the couple having moved off. She approached it gingerly, testing and pressing the ground with her boots before moving forward. As the rocks fell away on either side, she was burdened by an oppressive knowledge of her own vulnerability. It wasn’t fear, just an understanding she was nearing her limit.

Looking down was like viewing the world through the wrong end of a telescope—there was no foreground to focus on, everything was at an immaculate distance, huge rocks transformed into small pricks of red stone and dark shadow. She felt her legs weakening, their strength seeping away faster than the march to the Roque.

The woman approached the minor breach, a V-shaped opening where the crumbling rocks created a small join, a deep emptiness on either side. It flashed through her mind how stupid it would be to fall here, to die surrounded by tourists. These swirling thoughts polluted her mind, stripping away layers of stoic impassivity.

She carefully placed her hands on the far side of the breach and positioned her body. Rocking backwards (not worth a goddamn!), she swung a leg forward, and then the other, pulling herself up slowly. Laughter floated by, at her? Yes. No. Doesn’t matter. God, this spit’s thin. She crawled onto the flat patch of rock. She didn’t trust herself to stand up.

She heaved her legs up underneath herself to balance better, before looking about. In front of her was the island’s centre spread out under the monolith’s shadow. The landscape seemed to be entirely comprised of valleys and ridges, sparsely populated by olive-green bushes and pine trees. It seemed a primal scene, yet that was a lie. Roque Nublo itself would remember a time the valleys were filled with water and the earth was covered in rich greenery. A time before the Spanish came.

Goddamn it, my limit.

The woman started to ease backwards, placing her feet with great delicacy, testing each foothold before relieving her weight onto it. She slipped a leg over the gap and spanned it. She moved her feet to face the rock face and gently pivoted around as she brought her other leg over. She now faced her direction of movement and more confidently made the last remaining steps to the ledge.

It hadn’t been cowardice, it hadn’t been bravery. She had got to the spit, but couldn’t stand up… Goddamn! She couldn’t stand up… Goddamn!

A strange, slow peace penetrated into her. The woman had tested herself, explored an avenue, now it was done. She felt exhausted, her tiredness was all she could focus on, and she was glad.

Later, when it was over, she dangled her legs over the edge of the cabildo and stared over the landscape for a long time. The woman had touched something larger than herself and she’d retreated; she wasn’t its conqueror but its recorder. She was not a hawk but a swift, soaring high. And she’d soared today, when she’d touched the Roque, bruising her fingers over the abdomen of Gran Canaria.

She looked at the rough procession of thin, coarse peaks. Above, a Barbary Falcon circled, a dark silhouette almost obscured by the sun. She smiled. ‘Damn hot day,’ she said aloud.∎

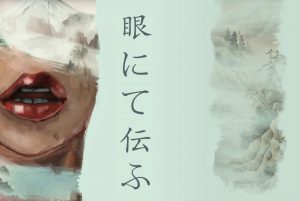

Words by Altair Brandon-Salmon. Photographic composite by Antonio Perricone.