Switching Off: The Pleasures of Idleness

Boredom today is the absence of a good 3G signal. I think that it’s worth asking whether or not that ought to be so – whether modern society’s conquest of boredom is something worth celebrating.

*

Boredom is the feeling we get when our surroundings imprison us – the feeling that there is nothing around us that amuses or engages. It’s a feeling that we’ve all had: John Stuart Mill declared that ‘a cultivated mind finds sources of inexhaustible wisdom in all that surrounds it’, but I imagine that even he would find a prison cell dispiriting. Boredom creeps up on everybody now and again, and it’s a feeling that most of us, it seems, will go to great lengths to avoid. Indeed, a recent study by psychologists at the University of Virginia found that many people doing a 15-minute stint in an empty room preferred to give themselves an electric shock rather than sit there with nothing to do. The participants thought that suffering a brief lack of stimulation would be worse than harming themselves. But were they missing out on something important on account of their fear of boredom?

Robert Pirsig once declared that ‘boredom always precedes a period of great creativity’. As it happens, experimental evidence suggests that he was right. Sandi Mann has shown that boredom can actually improve our ability to think inventively and pursue lines of argument or flights of fancy without distraction. And Andreas Elpidorou has argued that even the most intractable sort of boredom can be good for us if we treat it as a signal from our bodies to forget about our surroundings. Shutting ourselves off from all the ‘noise’ gives us time to think about the big questions: Am I happy? How can I make my life go better? Those questions loom large in everything that I’ve written here.

*

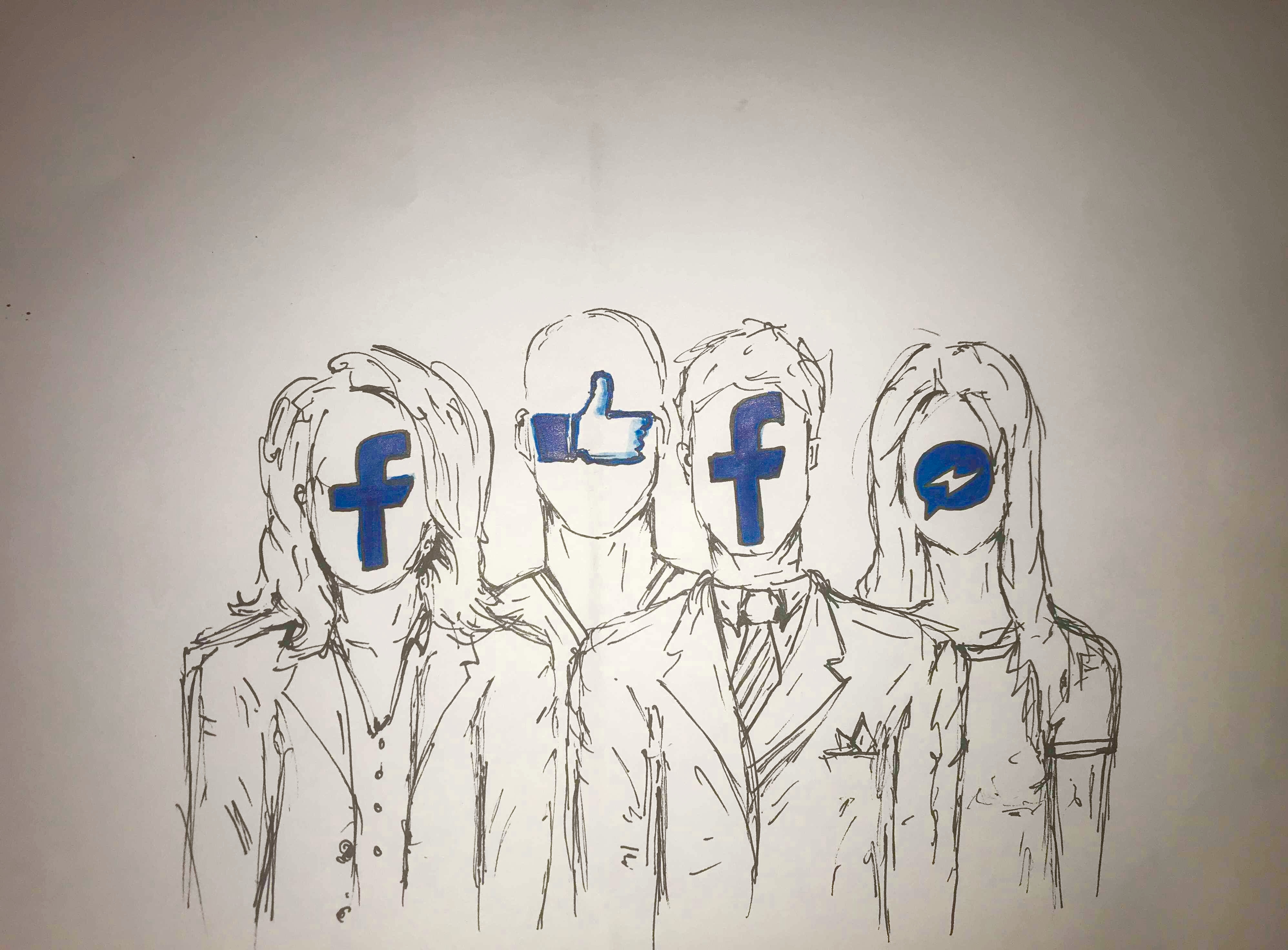

In 2018, we live in a world where there is always some digital superficiality on hand to divert and distract us. As such, our surroundings no longer imprison us – they no longer drive us to boredom. Not only does this deprive us of its creative benefits, it also means that when the iPhone goes flat or the Samsung Galaxy Note self-immolates, and boredom strikes anew, we realise that we’ve lost the capacity to relieve it of our own devices. We find ourselves with what Robert Louis Stevenson described so presciently as ‘a mind vacant of all material of amusement’, lacking even ‘one thought to rub against another’ in the event, say, of having ‘to wait an hour or so for a train.’

Overreliance on our hardware is not the only price that we’re paying. Our methods for alleviating boredom are partly to blame for the political malaise that the West finds itself faced with today, because they have given us near total control over what appears on our television sets and smartphone screens. Coupled with an entirely natural (if self-indulgent) instinct to seek out more of what we know and like, this control means that we spend much of our lives reading, watching and hearing exactly what makes us comfortable. Our echo chambers have become so spacious that our drive to find something interesting to do never prompts us to go beyond our own network – to meet on equal terms with those who belong to other tribes. To put it succinctly: because we can now hear it told to us in ten thousand different ways by ten thousand different people, the ‘story of exactly what we want to hear’ will never be boring again.

The list of side effects goes on: our techniques for boredom prevention are diminishing our attention spans and reducing our tolerance for inactivity. In doing so, they’re contributing to a slow loss of our capacity for carefree and untroubled idleness. This is something that we should all be disturbed by, because it robs us of the ability to experience what are in my opinion some of the happiest moments in life – moments of real leisure. How can we fail to be charmed by some of the ‘Thirty-Three Happy Moments’ of Chin Shengt’an (a Chinese critic)?

(i) To cut with a sharp knife a bright green watermelon on a big scarlet plate of a summer afternoon. Ah, is this not happiness?

(ii) To find accidentally a handwritten letter of some old friend in a trunk. Ah, is this not happiness?

(iii) To open the window and let a wasp out of the room. Ah, is this not happiness?

(iv) It has been raining for a whole month and I lie in bed in the morning like one drunk or ill, refusing to get up. Suddenly I hear a chorus of birds announcing a clear day. Quickly I pull aside the curtain, push open the window and see the beautiful sun shining and glistening and the forest looks like having a bath. Ah, is this not happiness?

We are in danger of losing these days when the mind slows down instead of racing ahead – these days when the whole feeling of each moment is savoured and enjoyed.

We would, ultimately, be better as well as happier people if idleness were to make a resurgence. Far from ‘doing nothing’, idleness involves (again in the words of Robert Louis Stevenson) ‘a great deal not recognized in the dogmatic formularies of the ruling class’: lounging about in the open air, enjoying quiet moments of reflection, taking due care of health and spirits, and learning The Art of Living Well. Because it takes time to recognise how people are really feeling, the idler is best placed to make those around her happier, and learns to take joy in doing so. Nobody has put it better than the seventeenth-century epigrammatist Chang Ch’ao: ‘only those who take leisurely what the people of the world are busy about can be busy about what the people of the world take leisurely.’

So I want to end with a rallying cry: let’s stop striving to avoid moments of boredom! A capacity for such moments was what allowed Walt Whitman to look up at the sky (a ‘sane, silent, beauteous miracle’) and tell us that it ‘has that delicate, transparent blue peculiar to autumn, and the only clouds are little or larger white ones, giving their still and spiritual motion to the great concave. All through the earlier day (say from 7 to 11) it keeps a pure, yet vivid blue. But as noon approaches the colour gets lighter, quite grey for two or three hours – then still paler for a spell, till sun-down – which last I watch dazzling through the interstices of a knoll of big trees – darts of fire and a gorgeous show of light-yellow, liver-colour and red, with a vast silver glaze askant on the water – the transparent shadows, shafts, sparkle, and vivid colours beyond all the paintings ever made.’ Is there a man or woman of Whitman’s calibre alive today who could truthfully say ‘I am sufficient as I am’?

Artwork by: Shauna Leigh Brown