Facebook: A Force for Social Change? An Interview with The Worldwide Tribe

Facebook was created as a platform for curating a network of friends and posting photographs, and whilst it remains home to many a funny collage on your friend’s birthday wall, it now takes on another role. Increased use of social media has led to a steady decline in the use of newspapers and radio; for young people at least, it has become the main source of news (Reuters Institute, 2016). The passive nature of online consumption and presence is often frowned upon – sharing a petition on your timeline will quickly earn you the label of a “slacktivist” (defined by the Urban Dictionary as ‘one who vigorous [sic] posts political propaganda and petitions in an effort to affect change in the world without leaving the comfort of the computer screen’). However, in a world where over 3.7 billion people have access to the internet, perhaps the causes we should be fighting for the are ones online. I interview Jaz and Nils O’Hara, siblings who founded the charity The Worldwide Tribe, about how they have harnessed the intangible influence social media has, and used it to bring about real social change.

The Worldwide Tribe utilises ‘creative storytelling’ to bring a ‘personal human perspective’ to global human rights issues. Both in their twenties, Jaz and Nils are in the perfect position to take advantage of what social media has to offer in their attempts to change the Western perception of the refugee crisis. ‘We’re coming to a new wave of the humanitarian sector and a new wave of charity which isn’t this old school Comic Relief style where you see babies with flies on their faces in Africa,’ says Jaz. ‘What we really try and do is creatively and innovatively use social media to re-work that narrative’. The charity tells the stories of individuals fleeing Syria, Eritrea and Afghanistan (three countries that make up the home nations of over 50% of those seeking refuge in Europe) through beautifully shot and produced films, which are then circulated through their wide online audience. Having followed their work since the conception of the charity in 2015, I was used to seeing The Worldwide Tribe on my Facebook and Instagram timelines, but was taken aback and excited to spot their iconic van (used for the many trips they make across the channel to Calais) parked on my road in Peckham. After establishing that we were neighbours, I interviewed Jaz and Nils in their kitchen, decorated with paper lanterns and complicated schedules for their upcoming projects – as is written on The Worldwide Tribe website, the world certainly is a remarkably small place.

‘Everything started for us through social media’; for Jaz and Nils, Facebook is not just a way of conveying a message, but the platform through which The Worldwide Tribe was born. In her TEDTalk, Jaz describes how after visiting the refugee camp in Calais known as ‘The Jungle’, she was left ‘emotional and confused by the way news reports conflicted with the reality of the situation’. Her first visit to the camp coincided with a wave of anti-migrant rhetoric, coming not only from the press, but from Parliament as well. The Daily Mail described ‘marauding migrants’, David Cameron warned against a ‘swarm’ – and yet the refugees she met there were ‘positive, incredible, [and] inspiring … the most humble, dignified, [and] welcoming people’. In a bid to provide a different perspective on the situation, Jaz wrote a Facebook post that night about her experiences. It gained unexpected traction. ‘Suddenly Jaz’s first post was seen by fifteen million people,’ Nils laughs, ‘it was a woah moment. Crazy’.

This story of overnight internet fame is a reminder that the explosive power of social media really does lie in the hands of the people. Sharing something on Facebook doesn’t require a degree in journalism, a sought-after position in a competitive news industry, or any adherence to a particular publications’ guidelines. News has never had such democratic authorship. Nils warns against this total freedom, however: ‘there’s definitely a danger, because you can get in a place where a lot of people are listening to you without there being any kind of boundaries … we don’t have to be un-biased, we can be as biased as we like; it’s our channel’. Whilst anyone with a smart-phone has great power, the great responsibility that should come alongside this isn’t always evident. ‘People are very much behind a keyboard’, Jaz says. ‘On social media you open yourself up to positivity, negativity … you stick your head above the parapet’. In some ways, the internet is a warzone like any other, and anyone going into the battlefield needs to be prepared to face onslaughts of criticism, because it fires from all directions. Paradoxically, being political online is both “vehement and unnecessary” (according to the Urban Dictionary), but also lazy “slacktivism”. It would be naive to think a Facebook status shared with your few hundred friends is going to change the world, and equally naive to think it is enough to place you amongst the ranks of great civil rights leaders. But there exists a space between these two extremes – the pathetic, try-hard pointless “Social Justice Warrior”, and the lazy “slacktivist” – in which the internet is actually extremely powerful.

In portraying the human side to the migrant crisis, the ‘human perspective’ offered by The Worldwide Tribe’s films and photography is essential. ‘The people that work in mainstream media are getting paid to write about news. We’re doing this because we saw the situation and wanted to help’, Nils notes. This different approach allows for a multitude of different narratives to simultaneously exist and build a more nuanced view of the situation. ‘Mainstream media is a lot about statistics and a lot about numbers and a lot about this many people died in the Mediterranean’, Jaz says. ‘Social media can introduce you to that person who lost their brother crossing the Mediterranean and you can feel like you’re getting closer to that person’. Meeting the humans behind the number makes the fundraising that The Worldwide Tribe does all the more effective. One of the individuals that the charity has posts about often is a twenty-seven year-old Syrian refugee, called Noor, whose final year of Law school was violently interrupted by missiles firing at Damascus University, leaving her wheelchair bound. Posts on The Worldwide Tribe’s Facebook page tell the story of Noor’s journey to Europe (a crossing that is hard enough for any able-bodied person), her medical condition and her desire to continue learning and finish her studies. The donation page that the charity set up for Noor and her family has raised over £7,000 to date. The Worldwide Tribe educates people through telling the stories of individuals like Noor, and in doing so is able to raise money with a transaction that is more personal than donating to large NGOs. Scrolling through their Facebook page reveals countless posts about the people that make up statistics, humanizing the numbers that are so often thrown around by mainstream media outlets.

When I ask about why they think this human perspective is so vital within political activism, they correct me; ‘We wouldn’t really call ourselves “political activists”’, Nils explains. ‘We’re a channel that tries to tell stories, we’re a story-telling channel. We’re not here trying to change the government, we’re here trying to tell people about these situations and raise awareness, and educate our audience about what’s going on so that they in turn can do stuff themselves’. And perhaps this is why The Worldwide Tribe has found so much success on social media sites like Facebook and Instagram, which were, after all, invented as story-telling platforms – albeit for a different kind of story. Whilst the work of The Worldwide Tribe has at times involved politics, such as campaigning on the Dubs Amendment legislation, Nils emphasises that ‘the humans in this crisis are more important than the political side, so telling their stories and then trying to change things from the ground up is a better way [of doing things]’. This is a refreshing perspective. Being a “Social Justice Warrior” online is not about a desperate attempt to convert likes and retweets into idealistic political victory. It’s about being a facilitator, an observer; about paying attention to the power that social media has to provide each of us with information and empower us, as individuals, to build a wave of change. Jaz tells me the story of Mohammed, a poet whom they met in the Calais camp two years ago. He’s a Sudanese refugee who had toothache, and despite suffering so much he couldn’t eat or sleep, was unable to see a dentist in Europe without the relevant papers. After writing a post on Facebook, however, they received offers from dentists all over the continent to help, and were able to facilitate one visiting the camp to treat him. The Worldwide Tribe works by connecting people’s stories, by sharing photographs and films – in essence, by using these social media sites the same way we all do. Unlike our own social media profiles, however, these invisible links cultivated by the charity manifest themselves in real social change.

But what about the negatives of a platform that is so easy to use? Syndrome, the villain of the The Incredibles, hands-down best Pixar film, famously argues that ‘Everyone can be super! And when everyone’s super…no one will be’, something which can be paralleled in a sense to social media activism. If fighting for social change is about changing your profile picture instead of chaining yourself to a fence, then suddenly we are all activists – but are we really achieving anything? Jaz and Nils are acutely aware of this, yet they protest the supposed futility of such a medium through emphasising the need for ‘tangible impact’. ‘People are very quick to shout their opinions on social media and I think it’s really important back up those with information from other sources, and also with personal experience’, Jaz says. A quick flick through my previous profile pictures on Facebook reveals I’m just as guilty as the next person when it comes to over-laying a flag filter over my face, and there is, of course, a fundamental difference between doing this and actually raising awareness. The scorn at those who declare their support for refugees via nothing more than a photo shared on Facebook is probably justified, and yet “slacktivist” shouldn’t become a blanket term for anyone using social media for social change. Jaz also points out the danger of the “echo-chamber” – a lot of the time, on social media, ‘you are just seeing the things that you want to see’. Facebook, despite being the most popular social media site for news, tailors content through algorithms, making the stories we see on our newsfeeds not necessarily the most pressing, but the ones we are most likely to connect with based on our previous likes. ‘We are constantly trying to get our content out to other audiences’, she explains, noting that this requires using social media in the ‘right way’.

Effectively raising awareness goes beyond reminding your own few hundred Facebook friends that you are pro-immigration, and involves tapping into new platforms and spaces that wouldn’t be otherwise accessible. Last year, The Worldwide Tribe worked with Copa90 – a popular football YouTube channel – to coordinate a football tournament called The Liberté Cup in a refugee camp in Dunkirk, Northern France. Collaborating with other channels is a way of breaking down the walls of the restrictive echo-chamber. ‘[People] realise, oh I like football, and these people like football too, so maybe we are all just the same’, Nils says. ‘We really try and use popular culture and things like that to engage new audiences,’ Jaz adds, explaining how they were inspired by the sudden craze of Pokemon Go to make a film that brought the game to the Calais Jungle, with the tag-line, If Pokemon can cross borders, why can’t a refugee?. Once again, we are reminded that there’s no better way to connect two people, even those with the most disparate of interests, than through social media. Whilst Jaz and Nils laugh at the fact that most of their Facebook audience is comprised of middle-aged women, films like Pokemon Go have been shared on platforms such as UniLad and LadBible. The power of a medium that can link, simultaneously, a forty-something year-old British mother with a South American teenager is not something to be brushed aside.

As more of the world and its population move online, fighting for social justice on the internet is more impactful than it’s portrayed to be. Whilst Britain’s press and politics often seek to build barriers between ourselves and the rest of the world, social media does the opposite, allowing us to connect people all over the globe; a glowing digital spider-web of lives that are all inter-linked. We need to stop criticising the politicisation of social media, and instead celebrate the incredible force for social change it provides us with.

For more information visit http://theworldwidetribe.com/

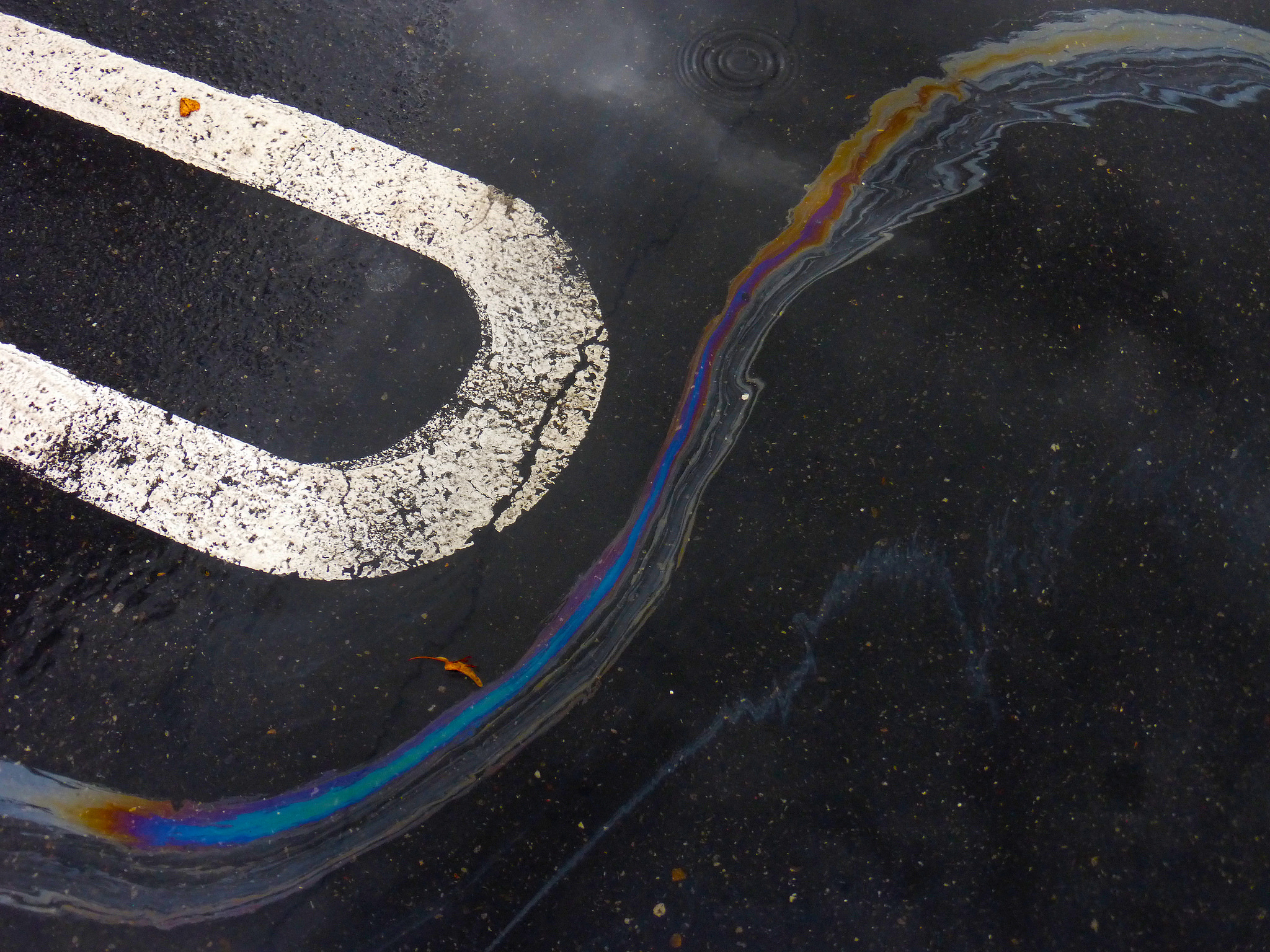

Illustration by Niamh Simpson