The Book of Everything

I had a vision of a book that was about Everything.

A grand, enigmatic introduction promised to reveal profound and mysterious connections between almost all things, and to conclude with a staggering revelation. But this introduction ended with an apology: a lot of explanation would have to be done first. This “explanation”, I read, in tiny font, would constitute a narrative that would run from the correct point to the final correct point, and, having read it once, the reader would really understand what it really is that is “Everything”. I excitedly turned over to the first chapter of this enormous and heavy book, and started reading.

Chapter One (there were many thousands of chapters) focused on verb choice in the explanatory textboxes of a particular beginner’s Guarani textbook, and how there was once a Viking man born in 1001 who, on an idle, grey day, while waiting for his friends, picked up a stick and scratched a few marks into it at random with his knife. These marks, when translated into plain English through what the book called “perfect and objective artistic interpretation”, produced a wry argument for why the verb choice in the aforementioned textbook  was an affirmation of the necessity of drugs companies’ independence from their parent bodies. This was fascinating to me. I wondered if the book could see into the past and the future. But the author also seemed keen to stress that no crucial points had been made yet, and that the Vikings and textbooks would eventually tie together

was an affirmation of the necessity of drugs companies’ independence from their parent bodies. This was fascinating to me. I wondered if the book could see into the past and the future. But the author also seemed keen to stress that no crucial points had been made yet, and that the Vikings and textbooks would eventually tie together

in some dazzling thesis that he was going to nail it in just a bit.

I flicked forwards a good chunk, and I found the next chapter to be about a cubic lightyear of empty deep-space an inconceivable distance from earth which, for half a second, in several aeons time, would flash purple for no reason at all and then return to black. Apparently, that future flash had a lot to do with a violent series of thoughts that a troubled French child called Ben had had while looking out of the wide windows of his living room on the first day of the tenth summer of his life to realise that, somehow, the leaves on the trees were already turning darker shades for autumn. “Bear with me” was the author’s tone. It was mentioned later in the chapter that Ben was the one human being ever to both have died and not died of Polio. He oscillated in and out of existence, and the on days and the off days of his life could be converted into ones and zeroes, numbers that could be systematised into a new language.

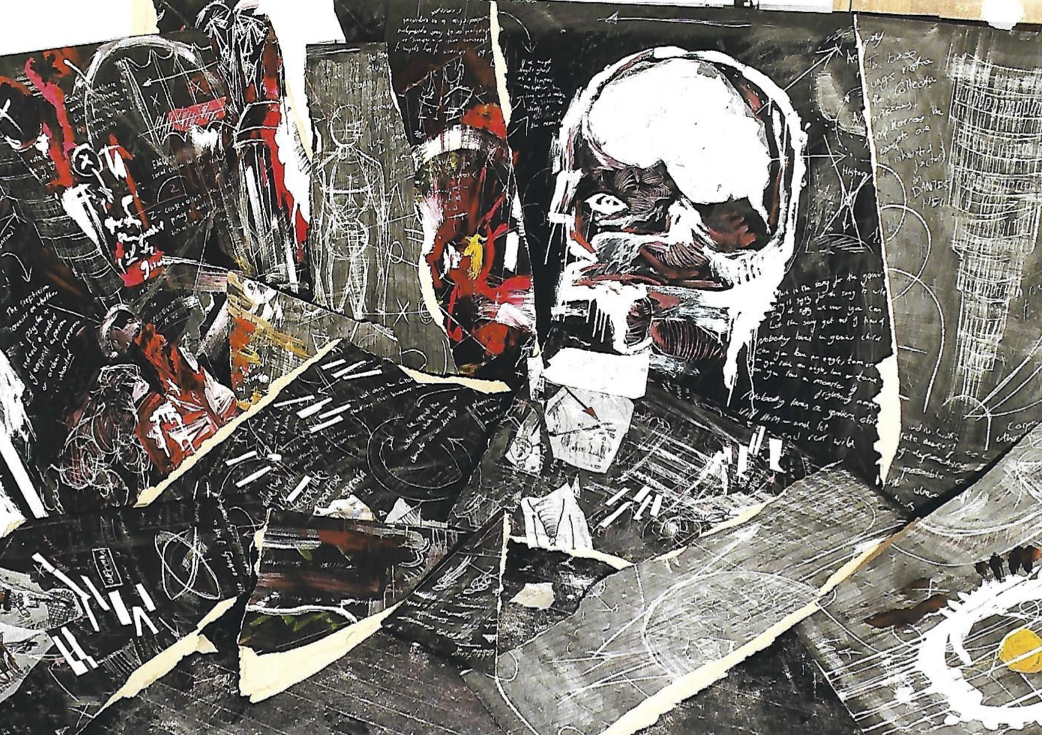

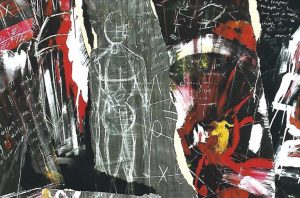

Not really following, I moved on. This section was more predictable in a Book about Everything; it discussed creation stories in various different religions and their related philosophies. The next page focused on Sprite, the drink. Then more philosophy, this time Plato and Siddhartha, followed by a series of images of renaissance paintings intersected by angular lines of code and numbers. The arguments in the captions of these pictures were staggeringly complex. I skimmed forward to a chapter titled “cobwebs and supremacy” and noticed that a few of letters, here and there, had been replaced by symbols I didn’t recognise. It was still readable, but the flow of information had accelerated and new concepts, locations and formulas were being introduced with every paragraph.

I flicked through at pace now, and however fast I went more pages seemed to appear at the back of the book. There were some pages which were all black with just a few careful white spots on them, some with just a few words. I realised how quiet it was. The words towards the back of the book were just symbols and numbers and strange pictograms and graphs, with the occasional earlier topic being raised, contextualised and then abandoned. I was tired and confused and dug my fingers into the final pages at the back. I turned the heavy weight of the paper over to see the conclusion, the final line that I knew would be beautiful, but by then, of course, the Book was written in a whole new language. Every English letter had been replaced by a symbol I didn’t recognise. I tried to flip back to the beginning but the pages wouldn’t move. I paused and looked at my fingers, and saw that they’d turned black with ink. I felt calm for a second.

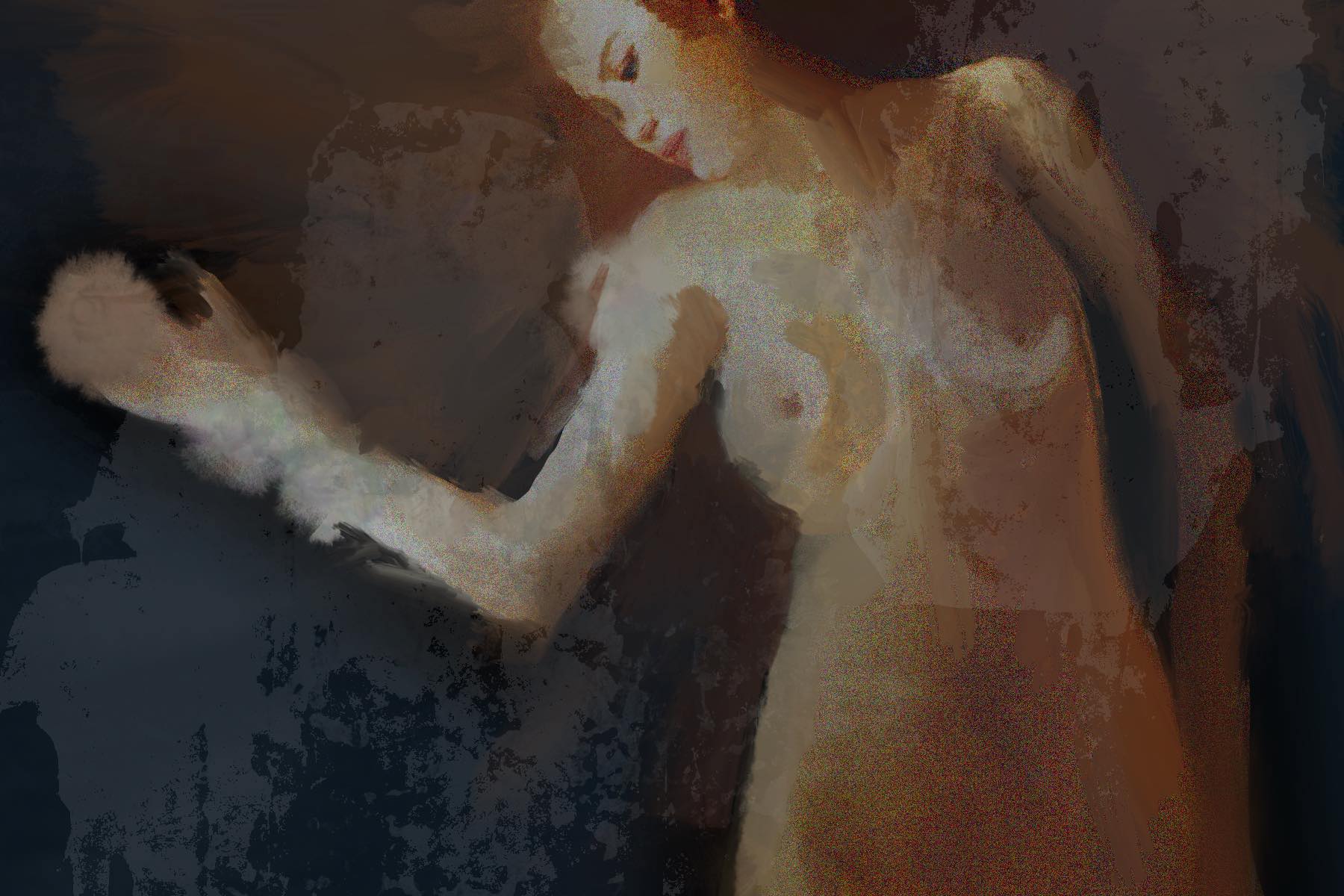

I didn’t want to sleep with Claire for several days after that. I kept turning over while we cuddled in the dark and the way the moonlight caught her cheeks made her face look like a skull.

Illustrations: Alex Matraxia