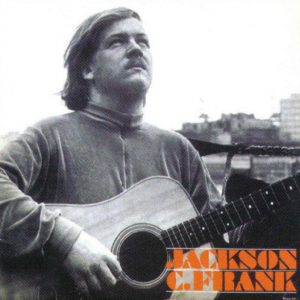

On This Day: Paul Simon

by Patrick Grealey | January 24, 2017

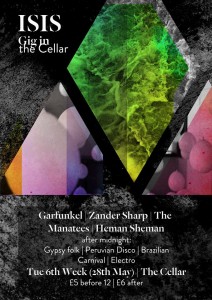

Anybody who, like me, spent at least one fifth of their childhood dinner-times in the welcome company of Simon & Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Water cannot have helped forming an opinion on the relative artistic merits of Art Garfunkel. For better or worse, it seems to me that Garfunkel was the definitive voice of Simon & Garfunkel: his solo passages were conspicuously poised performances of angelic earnestness, while everywhere else he was the shadow that danced behind Paul Simon’s melodies, ebbing and morphing into the virtuous descants and harmonies that now seem at a glance to be their signature — no doubt Art himself would have you see it so. But if this is really their signature, on what legacy can it sign off? What authority does it really wield? For harmony-heavy folk-rock was hardly an under-tested style in the mid-to late 1960s, and while decorative vocal interplay may have typified Simon & Garfunkel as a duo, it was ultimately a façade that prettified an already elegant structure, one whose chief architect was Paul Simon. Put a little more bluntly, while Garfunkel was fortunate in being one of the more distinctive voices of many in the populous folky milieu, his real lucky break was being the one who got to sing ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’.

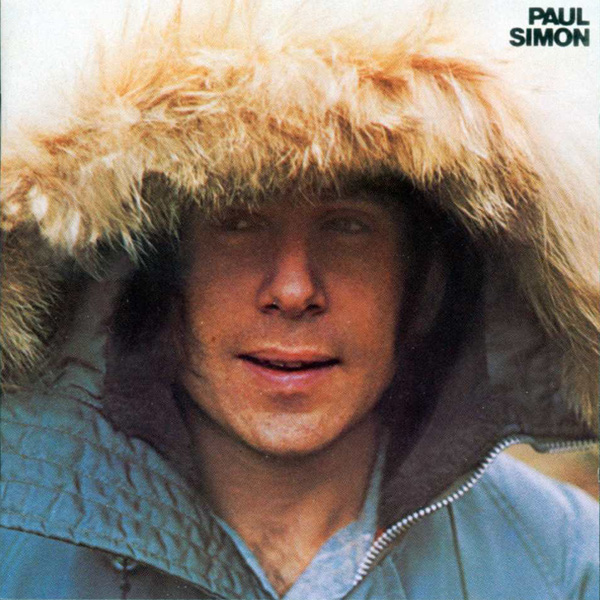

I don’t mean to assassinate poor Artie’s character here; it’s just that I spent another fifth of my childhood dinner-times in the welcome company of Simon’s Greatest Hits: Shining Like a National Guitar, and never did I think to miss Garfunkel (nor did I ever wonder when I was going to hear his greatest hits). Sure, he had his uses, and was worthy enough of the role he played, but it was Simon whose writing defined what those uses were, and who had more great ideas than one might know what to do with, to which the flair and diversity of Bridge Over Troubled Water attest. As it happens, the recording process of Bridge Over Troubled Water, problematized by Garfunkel’s eight month commitment to filming Catch-22, saw the Simon & Garfunkel relationship strained to a point of critical tension. Eventually the two parted professional ways in 1970, not without bitterness, and Simon set about seeing what scrumptious delicacies he could cook up without the Garfunkel seasoning; the resulting eleven-course meal was simply titled Paul Simon, and was released in 1972, forty-five years ago today.

And it’s pretty delicious, to say the least. Every song offered on Paul Simon is incandescent with the energy of an already proven semi-genius making the final quantum leap outwards. As much as anything else, it’s the economy of Simon’s craftsmanship that seems both to assure and define the album’s success, a trait that almost by definition goes unnoticed until the dwindling of the final notes, upon which you realise your attention hasn’t faltered once. For while Simon’s song-writing before Paul Simon had never wanted for imagination — be it structural, melodic, instrumental, harmonic etc. —here the proverbial cup seems as if it might run over, were he not so judicious in the handling of his ideas. Yes, the cup runneth, but only to the very brim. The thing’s as trim as a marathon runner before breakfast too, with only one of the album’s eleven songs entering a fifth minute, and with five others not even making it to a fourth. But each one of them is its own little revelation. It’s not just that there isn’t a middling song on show: there’s barely a middling minute, barely a middling bar.

Certainly, it’s nigh on impossible to close one’s ears to an album that opens with a song like ‘Mother and Child Reunion’, a movingly jubilant and effortlessly handled experiment with reggae that in 1972 would have still sounded new to many. And from thereon in you’re spoilt, by both variety and quality, from the meditative and mournful ‘Duncan’ (which fills the panpipe quota early on, thankfully) — through the waywardly bluesy ‘Everything Put Together Falls Apart’, the sauntering yet agile ‘Run That Body Down’, the leisurely then breathless ‘Armistice Day’, the gloriously giddy ‘Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard’, the troubled and mystical ‘Peace Like a River’, the wearily waltzing ‘Papa Hobo’, the goofy and barn-rattling ‘Hobo’s Blues’, and the gutsy and cranky ‘Paranoid Blues’ — to the sorrowful but slightly sly ‘Congratulations’. Musically, each song has its distinct tone, each different from the last, and each achieved via the combination of Simon’s holy talent for naturalizing striking melodies within curious harmonic structures, his vital, quietly virtuosic guitar-playing, and the smart deployment of the multifarious arsenal of background instruments and instrumentalists he puts at his disposal — Larry Knechtel’s organ and Wurlitzer on ‘Congratulations’ and Stéphane Grapelli’s violin on ‘Hobo’s Blues’ are particularly special adornments. Everything justifies itself, and nothing tires, with Simon never taking anything further than it deserves to go.

I can’t help concluding that the absence of Garfunkel is a crucial and positive contributing factor to the specific merits of Paul Simon. Simon is lyrically freer to channel and his worldview as explicitly his own worldview. He’s also musically delimited, at liberty to write melodies at the service — and to the requirements –—of his voice alone, and to foreground that voice within arrangements characterised and led by his own stylistic inclinations and inspirations. The same, of course, is true of any artist taking the first steps out of a collaborative past and into an independent future. But in the case of a talent as immense and intense as Simon’s, those incremental increases in freedom count for even more, and the scope for experimentation and artistic self-realisation widens to a greater degree than in the case of a lesser artist. And although I preferred the relative grandeur and generality of Bridge Over Troubled Water at the time, I could sense this greater flexibility and idiosyncrasy in those solo-Simon hits I used to dine to as a cautious youth, from the gems of Graceland to the mini-dramas of Hearts and Bones. Those and other albums were all waypoints on the road to the horizon of his genius that Simon has followed since Paul Simon; Paul Simon sees him hitting that road at a full Olympian sprint, as if it were the easiest thing in the world.

Photo: Emmanuel Lodieu