On This Day: Songs of Leonard Cohen

I can recall it clearly: that scene in Richard Curtis’ Pirate Radio paean The Boat That Rocked wherein the comely Marianne has been wickedly lured away from the virginal clutches of the film’s protagonist Carl. As the poor youth sits ruminating on lust unrequited, in skips Leonard Cohen’s ‘So Long, Marianne’, deftly imbuing the scene with wistful cheer — or cheerful wist — as our hero’s luckless pals cajole him out of his undersexed misery through the redemptive power of circumstantial camaraderie.

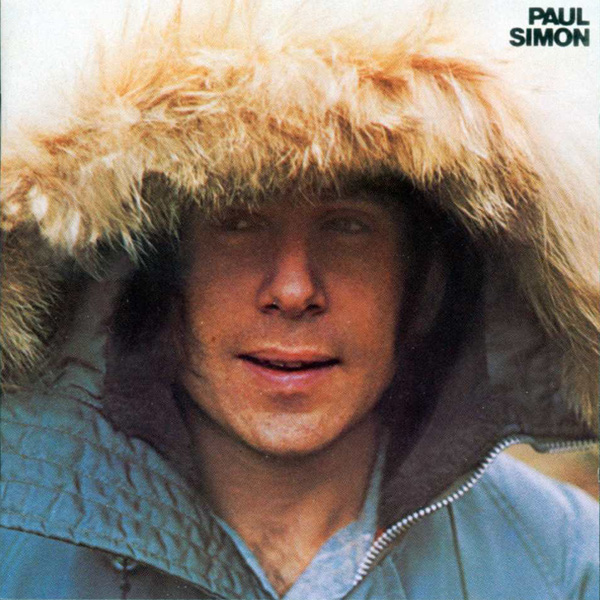

Prior to viewing Curtis’ film, my knowledge of Cohen’s work had extended little further than Rufus Wainwright’s gorgeous cover of ‘Hallelujah’ and the vague connotations of melancholy that Cohen’s name carried. Being the young and ambitious musophile that I was, Cohen was somewhere on my subconscious to-do list, not too far from the top but not yet quite ripe for inspection either, perhaps thumb-twiddling between My Bloody Valentine and Tupac. But the charms of ‘So Long, Marianne’ — Cohen’s directly oblique lyrics, the chord progressions that roll easily and undoubtedly towards the chorus, and the ABBA-esque backing-vocals found there— lit within me a flame of curiosity . So, I headed straight for the source, namely Cohen’s debut, Songs of Leonard Cohen, released 27th December 1967, 49 years ago today.

In the cases of all pop musicians, but perhaps especially in those of singer-songwriters like Cohen, there exists a dialectic between the musician’s persona and the music allied to it; songs add detail to the persona while the persona provides the main context for those songs’ interpretation. But it is invariably the content of an artist’s debut that triggers this dialectic, the first data with which a listener can begin constructing this persona. Songs of Leonard Cohen, in this regard, is a remarkably complex manifesto that yields a well-defined outline of the Cohen character, and perhaps unsurprisingly so. By 1967, Cohen was a 33 year old published poet and novelist who had spent most of the 1960s hidden away on the Greek island of Hydra riding the Amphetamine Highway to literary self-realization. As such, on returning to the Western hemisphere in 1966 and entangling himself in the New York folk scene, he already had the maturity and experience that would translate into the debonair mystique that has since defined him.

Indeed, the lyrics seem both to combine and juxtapose the poetical and the novelistic. Often they dance at a metaphorical distance to the beat of a narrative that is felt more than understood, like in the mini-epics ‘The Stranger Song’ and ‘Master Song’, wherein each verse conjures a new dream in the series. Elsewhere, the most prosaic, conversational lyrics are somehow the most disarming, like when he shrugs tenderly to the listener of the ‘Sisters of Mercy’ that ‘you won’t make me jealous if I hear that they sweetened your night/We weren’t lovers like that, and besides, it would still be alright’. The finest synthesis of these two impulses comes on the album’s final song, ‘One of Us Cannot Be Wrong’, an effortlessly vibrant portrait of lovelorn helplessness. All over the album Cohen coolly flexes his own literacy, which is yet by no means beyond Everyman comprehension, and this, combined with a broad yet balanced focus on love, establishes the Cohen we’ve come to know: the well-read, well-written rake who sees the world through romantic eyes but is wary not to let himself be ruled by a jealous heart.

Even at his most high-flown lyrical moments, Cohen avoids, for the most part, the pomposity that blights so many singer-songwriters, particularly those of his own era; regardless, he earns the indulgence of his words with the nimbleness of his singing. Deceptively amateurish, lacking in any systematic idiosyncrasies, and rarely rising above speaking volume, his voice is as sure-footed as it is insouciant, and establishes an impression of casual honesty that guarantees the safe digestion of lyrics that, rolled off the wrong tongue, could easily curdle on the way down. At his most lyrically unambiguous moments, this delivery affords Cohen a sense of openness that at once bypasses and augments the silhouette of the winking intellectual that he for the most part casts.

Even the arrangements that hang around Cohen’s songs are teasingly tasteful, their modesty matching the unfussiness of the chords-and-melodies that underpin them. Central is Cohen’s sweetly plucked nylon-string guitar, which seems to owe as much to flamenco as it does to folk, and around it swirl all sorts of novel but unintrusive accoutrements: accordions, mandolins, flutes, harps, (mercifully) quartet- rather than orchestra-style strings, and even some snatches of bass and drums. This apparently contravened Cohen’s vision of the album as a rather bare affair involving just him and his guitar, but, if anything, these adornments underscore the worldliness integral to Cohen’s shabby-mystic character, that of a man who’s as at ease humming his ditties out the front of a Parisian café as in some Californee saloon, with the help of whoever might be recruited in each.

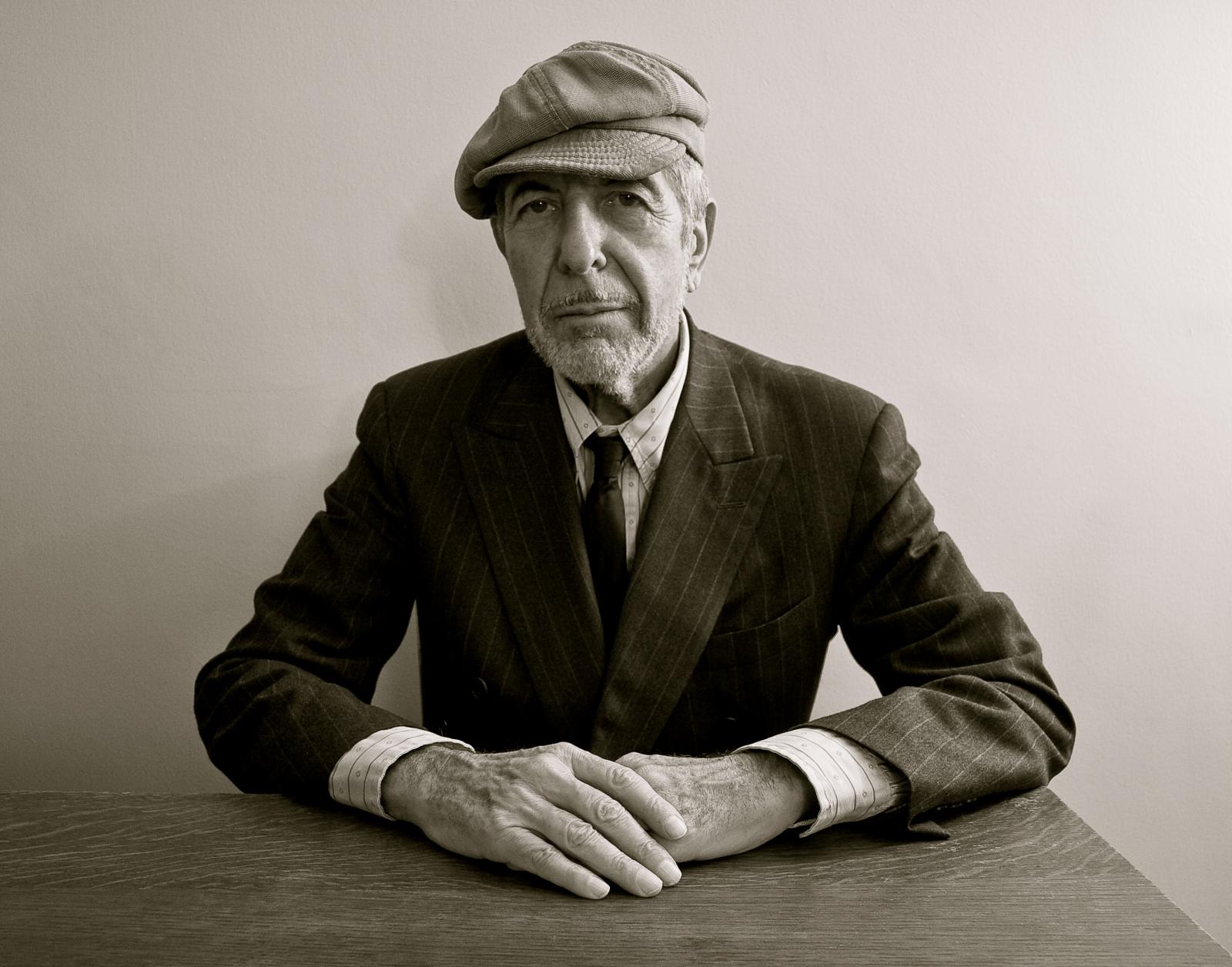

All these things help to explain why that ‘So Long, Marianne’ scene is so effective. Poor Carl, adrift in a world to whose relative decadence he aspires but for which he is not yet ready, and too young and inexperienced to know either romantic success or failure to any meaningful degree, is cast against the musical missive of a man old and experienced enough to know both in detail. In that teenage way, he feels that he has experienced in a matter of hours what Cohen experienced in a matter of years with Marianne Ihlen, and the snippet of the song that it takes for Carl to be cheered up highlights both the intense depth and the fleeting superficiality of his emotional turmoil. Such is Cohen’s exemplary value as a songwriter: he analyses his own condition in an insightful and intelligent way that can be appropriated and substituted for one’s own self-reflection, and that never seems to fail to do justice to one’s personal experiences. All pop music can do this — indeed, it’s one of its primary functions — but few musicians could do it in such an amiable and intriguing way as Leonard could. What a shame it is that I have to use the past tense to say so.

Photo: Peter Gabriel