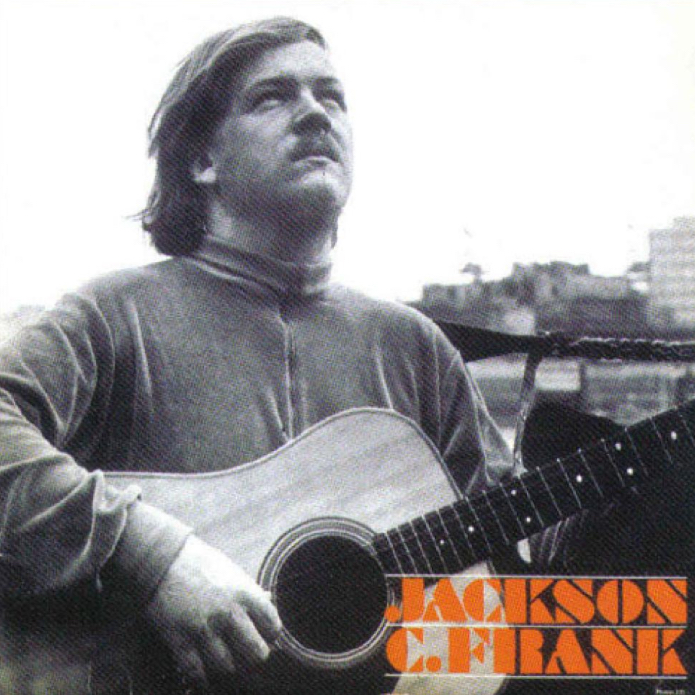

Retrospective Reviews II: Jackson C. Frank

One of the most influential folk albums of all time is shrouded in mystery. Jackson C. Frank’s life story follows a classic ‘tortured artist’ trajectory: depression, schizophrenia, a childhood accident resulting in severe and lasting burns, musical failure, and an early death at the age of 56. On paper, this is perfect documentary-fodder (think Searching For Sugar Man, the 2012 film which tried to uncover the mystery of the cult 1970s album Cold Fact). Yet, Frank remains criminally undersold in the story of folk music since the 1960s.

In 1965, Jackson C. Frank released his first and last album. The self-titled record was recorded on a winter’s day in London in just three hours, and was produced by Paul Simon. His crippling shyness meant that he had to ask to play from behind a screen, so those in the studio couldn’t see him. The only instrumental credits on the album are Frank, playing acoustic guitar, and the songwriter Al Stewart, who played a picked guitar part on the song ‘Yellow Walls’. The resulting sound is understated, intimate, and intense.

The album begins with his best-known song, ‘Blues Run the Game’. As is the case with so many songs—Hallelujah, Twist and Shout, I Heard It Through the Grapevine—the cover is better known than the original. Simon and Garfunkel’s 1966 cover of ‘Blues Run the Game’ has somewhat masked Frank’s songwriting, although for many people—including me—Simon and Garfunkel acted as a way into discovering Jackson C. Frank.

The second track, ‘Don’t Look Back’, sees Frank at his most rousing and purposeful, his voice booming out over strummed chords as he sings about the civil rights movement in America. “Don’t look back over your shoulder/Keep your eye on freedom shore”, he entreats, referencing the Mississippi-based civil rights activist Medgar Evers and “the bells of Selma”. He mourns the continuing deaths of black people in America: “Just another death for justice/Another sorrow that’s yours and mine”. Although not a canonical civil rights song in the vein of Bob Dylan’s ‘Oxford Town’ or Billie Holiday’s version of ‘Strange Fruit’, ‘Don’t Look Back’ seems to me a more powerful statement of hope than these classics.

This sense of cultural engagement and activism runs alongside the album’s sense of profound interiority and isolation. On ‘I Want To Be Alone’, a hauntingly delicate guitar melody is paired with a sombre vocal line: “I want to be alone/I need to touch each stone/Face the grave that I have grown/I want to be alone”. Heartbreak, rejection, and depression are explored in ‘You Never Wanted Me’ and ‘Here Come The Blues’. ‘Yellow Walls’ begins with an evocative description of “Yellow walls that shine like silver”, before the shine fades, and Frank’s wavering voice calls out: “No one knows me in the morning/No one sees me go walking by”.

Everything about it is unassuming: the guitar playing is subtle yet intricate, the vocal is delicate yet so often seems to mask something passionate and visceral, and the production is so simple it seems like Frank is playing in the same room as you. Yet it would be difficult to overstate the extent of the album’s influence. Three of the most important folk artists since Frank’s album have been profoundly influenced by it: Simon and Garfunkel, Nick Drake, and Laura Marling. The posthumous compilation album Family Tree, made up of home recordings by Nick Drake, is peppered with Jackson C. Frank songs. At one point we hear a recording of Drake saying, “I can’t think of any other songs to do. What could I do that would be interesting?”, before playing ‘Milk and Honey’ from Frank’s debut. Frank may have also worked with Paul Simon, but their career trajectories were completely opposing. Simon rose in fame, his career culminating in the lively and experimental Graceland, whereas Frank’s music was—like him—mostly shy and apologetic, and he faded into obscurity.

Just like Jeff Buckley, or indeed Nick Drake, both of whom died much younger than Jackson C. Frank, it is partly his slender discography that adds to the mystery surrounding him. One studio album, and a few posthumous compilations of home recordings and unreleased material, are all that remain of Frank’s musical career. But although he never achieved real fame during his lifetime—or indeed since his death—the album today is an endearing gem from a tragically forgotten artist.