Whippersnapper

by Joanna Kaye | June 1, 2016

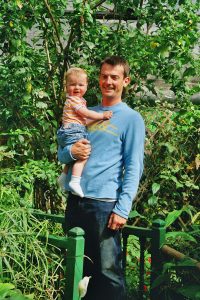

You called the dog Whippersnapper because you could not remember its name. You were friends, allies of sorts, with your illicit trades under the tabletop: a corner of your cake slice exchanged for a wag of the dog’s tail or a stroke of its black head for a friendly grin. But you could not even remember its name. Details like these were the first to disappear, and there was no way of knowing what would be next: my name, perhaps? My sisters’, my father’s, or even my mother’s—your own daughter? The disease had no limits, no morals, no conscience. It was relentless; a thief, stealing possessions one by one, leaving no visible trace of its invasion. The losses were not immediately acknowledged: not until the ransacked home had nothing to offer but the naked building’s framework. The thief would then take that too. He would tear away the wallpaper, strip the floor, pull apart the electrical wiring, ease the glass from its frame, and, in his sadistic game of Jenga, he would enjoy pulling the bricks out of their careful alignment, waiting until you collapsed, crumbled, obliterated yourself into a mound of indistinguishable rubble.

For us, that crumbling was gradual. Conversations were constructed in circles, the diameter deceptively expanding only to shrink moments later. Where are we going? Isn’t it lovely/awful/strange weather? What’s the dog’s name? To the supermarket. Yes, it is. His name is Sam. Old Whippersnapper. What happened to the old dog? She died. What’s this one called? Sam. There were strained voices, forcefully participating in replaying conversations as we chased each other round and round a circular track, occasionally attempting to lead him off into the unexplored territory of topics as yet undiscussed and questions as yet unanswered. Only to be back at this: Old Whippersnapper. What’s his name?

For us, it was terrifying, until it wasn’t, until it became normality, with yesterday already dissolved into non-existence, until moments became isolated in the present, unable to be converted into memory, until it was commonplace for meals to be left forgotten and uneaten, and whisky glasses to be kept on the top shelf of the fridge. It was painful. Repetitive. Tragic. Monotonous. Upsetting. Inspiring. You did not crumble. Not really. You maintained your dignity. You maintained yourself. You were an off-balance stack of bricks, tottering occasionally, yet resisting gravity. You still laughed and you still whistled and you still wandered around the garden, plucking the deadheads of withered daffodils. You remembered us, your family, and this, your home.

But for you? What was it like for you?

In flashes. That is how it would happen in Hollywood: in a dizzying blur, as honey-lit scenes reduce to pixelated grey. Memories would be relived for a second time, but just as you stretched out to retrieve them for safekeeping, they would burst into flames. Your scorched fingers and the ash confetti are from a fire you do not remember. A poetic, romantic idea: an ending in blazing colour, a beacon illuminating the dark horizon, a fanfare screaming through the night.

And then what?

A vacuum. An infinite darkness stretching onwards and outwards and inwards and endlessly. The credits. Then the rest of us leave the cinema, popcorn trodden into the carpets, back to streetlights and car horns.

But for you? Forgetting is never like that. Forgetting does not allow you convenient last farewells or moments of consideration. Forgetting is the crumbling, the disintegration, the fade-out into nothing. It is momentarily losing the distinction between your wife and your daughter, as you slowly condense everything into one: into one, single, obtainable truth; waterproof, fireproof, thief-proof, and perfectly immortal against the grappling hand of dementia. Forgetting is just that. It is replacing substance with absence. It is a whitewash, ready to be painted new.

And then what?

Image by Marius Strom