Untold Stories: Afghanistan in the 1960s

A particular narrative within the national media seems to have developed with regards to certain ‘war-torn’ countries in the Middle East. War-torn: the word implies destruction with a degree of permanence, as though they have always been ravaged by conflict, and always will be. This narrative is exacerbated by the common perception of a homogenised ‘Middle East’, purely defined by the various bombing campaigns inflicted upon them. One has only to look at the response to recent terrorist attacks in Europe to see what I mean: after the Paris terror attacks, national monuments and Facebook profile pictures alike were splashed with the red, white and blue of the tricolour. Meanwhile, the flags of countries such as Syria, Lebanon, Pakistan and Afghanistan remained largely ignored, due in no small part to this persistent narrative that paints them as ‘war-torn’—suspended in a state of continuous violence, where individual tragedies are unimportant. In short, these countries are defined solely by their association with Western violence. There is no sense of a past, of a history beyond this conflict.

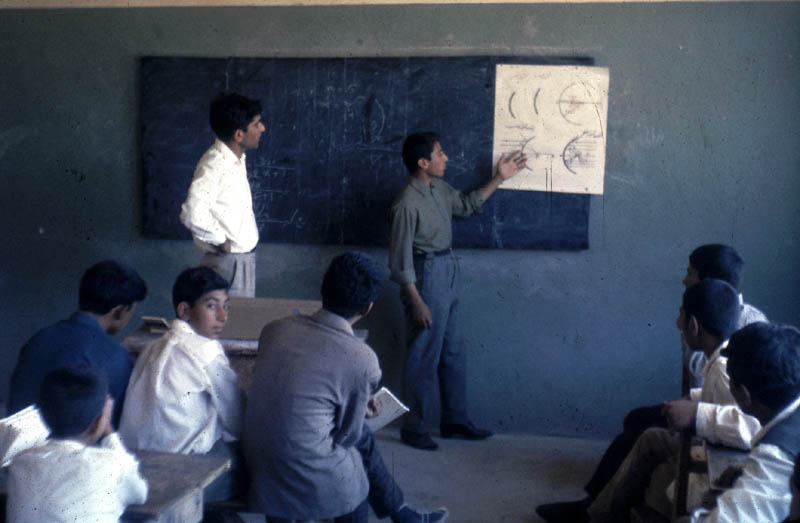

Of course, this doesn’t mean that there isn’t a story to be told. The photos of Dr William Podlich, taken in the late 1960s, present a chapter in Afghan history unknown to many. Under the reign of King Zahir Shah, the country was moving forwards, with the need for modernisation clear in the wake of the Second World War. Amongst a plethora of changes came the 1964 Constitution of Afghanistan. This provided a new parliament, to be elected through universal suffrage, and movement towards female emancipation, including the encouragement of female education and work outside of the home. This brief time of stability was eventually shattered with the bloodless coup that led to Zahir Shah’s abdication in 1973. Podlich’s photos demonstrate beautifully this lost time, featuring girls on their way to school, European holidaymakers mingling with local Afghans, and all the beauty the Afghan landscape has to offer. Certainly the scenes are mundane, but take on a particular poignancy in their sheer contrast to the tanks and Kalashnikovs normally associated with Afghanistan.

So pervasive is this association of Afghanistan with violence and conflict, that the peaceful stories my family members tell me about life at this time shock me. My maternal grandmother tells me stories of her life and childhood in northern Afghanistan. She describes her summer holidays in the orchards of Chahar Bolak in exhilarating detail, the vast gardens, the horse and carriage they would ride from village to village, and the clothes she would wear, t-shirts and skirts, without her hijab. My other grandmother talks of her days at school, during which, as she firmly tells me, “we would learn everything the boys did.” My grandfather’s description of his time at Kabul University doesn’t sound dissimilar to my experience as a student at Oxford. He tells me that the government gave students an allowance for their books, for food and clothing. “During Zahir Shah’s reign”, he explains, “education was treated as the most important thing. They provided well for students to encourage us to go to university, so that Afghanistan’s population would remain educated.” He describes field trips to the majestic Buddhas of Bamiyan, during which students learned about Buddhist faith and culture—again, a far cry from the religious dogma most would associate with recent Afghan history. Education was free, and travel was paid for—Kabul was a ‘student’s paradise’ he tells me emphatically. His only regret is that he didn’t know the value of a free education at the time.

These stories exposed to me a side of my country I hadn’t been aware of, and only reinforced the dangerous nature of the ‘war-torn’ narrative. Yes, Afghanistan is, and has been in the past, a troubled nation. However, that certainly isn’t the be-all and end-all of the situation. For too long, Afghanistan, and many other countries, have been treated as a chaotic mass, a million miles away from the West. Refugees coming from these countries are too easily villainised, because there is a fundamental lack of appreciation for their history outside of war and conflict. They are supposedly coming to benefit from the easy life in Western countries, because their countries, we are told, are ruins beyond repair—far too easy to be left behind. What many cannot appreciate is that what is in fact being left behind is a home, a society, a culture, and a history, the memory of which endures even during the fiercest of conflicts.

My grandmother tells me that the reason she loves returning to Afghanistan is that she feels well there, as though all her aches and pains have disappeared. After all these years it still holds a special place in her heart, and she’s never seemed prouder than now, when she tells me of those few tentative steps Afghanistan made towards independence and modernisation—steps which she hopes can be repeated in the not too distant future.

Image credits Dr. William Podlich, with thanks to Mr Clayton Esterson for giving us permission to use them.