Roadkill

High in a eucalyptus tree, Jeanie was woolgathering. ‘Yo ho, yo ho, a koala’s life for me!’ she suddenly whooped, breaking out from her daydream and pulling a face at Gus, who peered nervously up at his cousin from the base of the tree. Little furrows appeared on his freckle-peppered forehead.

‘Won’t you come down now, Jeanie? You’re scaring me!’ he called. She had been up there for almost an hour, and he was getting very hot and bothered. It was January, and the kind of day that gran would have called ‘a stinker’. Everything looked tired. It hadn’t rained in weeks. In fact, it seemed to Gus as though nothing at all had happened in weeks.

‘Look!’ Jeanie cried, ‘Look over there!’ She was pointing at something in the distance, something that Gus couldn’t see from the ground. A row of pesky pittosporum trees, the ones gran used to call weeds, blocked his view of whatever it was that had managed to catch Jeanie’s ever-wandering gaze. Those trees were thriving though, and it was a source of wonder to Gus that gran had thought them any less deserving than the dry, anaemic looking eucalypts. They looked so fresh and lively, compared with the ghostly-white eucalypts.

‘What is it, Jeanie?’ he called, ‘What can you see?’

In answer, Jeanie gave a piercing scream. In seconds, she was down on the ground. She was sobbing now, as she ran down the long dusty driveway towards the gate. Gus jogged after her. When they had gone through the gate and stood by the side of the highway, it was Gus’s turn to scream. Following Jeanie’s pointing finger, his gaze settled on the medium sized bundle of fur by the side of the road.

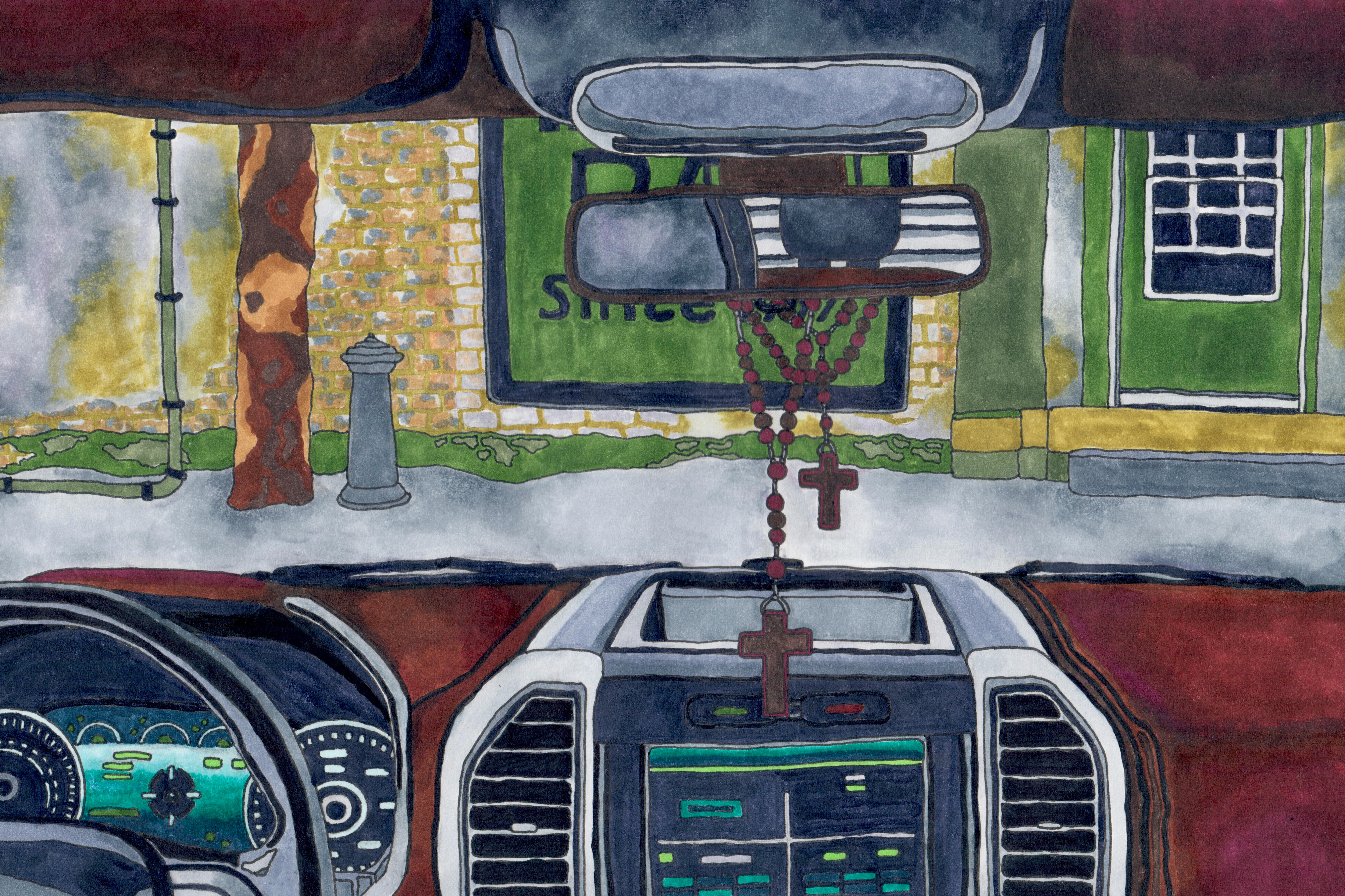

‘They just moved it to the side, got back into their car and drove off,’ Jeanie said. The two stood, stunned and staring, stopped dead in their tracks. The koala stared back, stretched out on its side with its head turned to face the two children. Gus shuddered. Jeanie wept. The koala’s carcass cooked under the Australian sun.

‘We’ll take it inside,’ said Jeanie. Her face wore a steely expression. Gus had never seen Jeanie like this, and it scared him. Anyway, he knew their parents would still be off wine tasting. He would make Jeanie get rid of it before they came back.

They carried the swinging carcass by the limbs. Jeanie supported its lolling head on her tummy. It was heavy, and surprisingly hot from the midday sun. Down the dirt track they went, up the driveway (empty of cars, Gus noted with relief), up the wooden stairs, and into the living-room. ‘On the couch,’ Jeanie directed, and so they propped up their guest on embroidered cushions and took up position on the couch opposite. The thing looked so lifelike that you might have mistakenly offered it a glass of orange juice.

‘What now?’ Gus finally broke out. Minutes ticked by, and neither of his companions offered a solution.

‘I don’t know,’ Jeanie finally admitted, ‘maybe we should just bury it.’ She wasn’t looking at Gus or their furry friend, but at something over her cousin’s left shoulder. He turned his head slightly to the left. There, on the mantelpiece, stood the small blue-wren that gran had had taxidermied after finding it in the garden all those years ago. The superb blue-wren, still resplendent with its iridescent crown and theatrical bandit’s eye-markings. Gus stared. The blue-wren stared back.

Silently, Jeanie arose and, leaving the room momentarily, returned with something in her hand. It was gran’s old sewing basket. ‘Help me take it outside,’ she simply said, ‘and bring me some cotton wool buds from the bathroom.’

When Jeanie’s mother walked in, Jeanie and Gus were sitting on the couch in silence, eating icy-poles. Before the words ‘Hi, kids’ had even escaped from her mouth, all the colour was drained from her face. She stood gaping, in total silence, as she stared at the furry interloper who sat, at perfect ease, in gran’s old armchair. Gus thought her face was as white as eucalyptus bark.

Image credit Kate Ausburn