Against movies

On the nineteenth of December, 2001, the corpses of two children were found in the water on the Oregon coast. Five days later, another two bodies were discovered. These were the bodies of the Longo family: MaryJane, the mother, and her three children, all of whom were under the age of four. They had each been strangled, packed into a suitcase and thrown into the water by their father, Christian.

Fourteen years later, the film True Story was released in the USA. Starring James Franco and Jonah Hill, the film is based on the memoir of the same name written by Michael Finkel, the New York Times journalist whose identity Longo adopted while on the run from the FBI in Mexico. Finkel’s career had previously taken a turn for the worse after he published an article on the African slave trade that veered closer to fiction than fact. Unemployed and publicly disgraced, Finkel saw this bizarre turn of events as an opportunity for a professional renaissance. He contacted Longo in prison, and so began the increasingly intimate relationship between the two that is detailed in the memoir. Finkel is reported to have earned $500,000 from True Story, a figure estimated before anyone had even contemplated adapting it into a film with an A-list cast.

The memoir and its subsequent dramatization have been labelled unethical and voyeuristic, as well as being seen as fuelled purely by mercenary desire. The most vocal of its critics is Penny Dupuie, MaryJane Longo’s sister. In an interview with the Telegraph, she condemned the film, saying, “It made me very angry … There should be a disclaimer at the beginning, ‘it’s a story by Mike Finkel’, to somehow excuse the things he’s done and make money. It’s about a murderer and a conman. There is not one thing about this film that does any good for the world. Nothing.”

Her anger is understandable: the man who imagined this film was actively seeking an opportunity to exploit a tragedy commercially. Perhaps even more frustrating for Dupuie is the film’s aspiration to hold some kind of moral high ground. Early on, the audience encounters the moment when writer and subject meet. The scene is staged as an ominously tense power play, with the two participants sat either side of a metal table in a prison cell lit so starkly white it makes your eyes wince. Finkel asks why Longo agreed to meet with him, to which Longo responds gravely that it’s “the way you stand up for people who don’t have voices”. It’s a less-than-subtle attempt to brand the film as a microphone for the marginalised voice, and claim that this story sits on the right side of the ethical boundary.

The filmmakers and Dupuie are somewhat misled in their estimation of where this ethical boundary lies. By expressing a belief that film must do “good for the world”, Dupuie is echoing an increasingly popular attitude that entertainment should not be produced without ethical considerations. Mary Ann Watson, a professor of media at Eastern Michigan University, asserts that “questioning whether a media production causes harm to the common good is a form of civil thinking”. This “civil thinking” sounds very admirable on the surface, carrying an implication that it is our societal duty to protect others from unethical productions. Her argument becomes more problematic when we consider that it is based on the brittle assumption that this form of entertainment can ever be ethical in the first place.

The process of watching film or TV involves the spectator being introduced to a scenario that will most likely hold little or no relevance to them. If we’re adopting real-life standards, this situation is none of our business and we shouldn’t be watching at all; the very act of witnessing the action before us is, in theory, unethical. In the early 1950s, the installation of televisions in a rapidly increasing number of American homes came with the “promise to transport viewers to the homes of fictional friends”. This is an unflinching commitment to both facilitate and encourage a strand of voyeurism. The viewer becomes a glorified Peeping Tom, somewhat questionably invited to the homes of these imposed “friends”.

It did not take long for this paradox to develop into an ethical minefield in the media industry. The Obscene Publications Act, enacted by Parliament in 1955, labelled a work obscene if it had a “tendency to deprave and corrupt”. In 1977, the act, initially aimed at literary works, was extended to encompass film, with the additional clause that a film could be exempted if it demonstrated “artistic value”. The questions of what form such artistic value took, and upon whose authority this was judged, were shrewdly dodged. Bernardo Bertolucci’s ‘Last Tango in Paris’ was one of the first to fall victim to the new laws, when its lurid sexual scenes were given a twenty-second chop by the British Board of Film Classification. But why, in the eyes of so many, were these sexual scenes more damaging than any other scene? And in a similar vein, why was the dramatization of Longo’s actions deemed unethical when equally violent films of the same year were met with such praise? Increasingly the public has been convinced that there are gradations of voyeurism, and that voyeurism can be relieved of its moral burden in some cases but not in others. This simply is not the case; the spectator is put squarely into the position of voyeur regardless of the content or artistic merit of the production.

From the roots of visual entertainment in Greek tragedy onwards, we’ve been watching our fictional friends carry out actions as comfortably distant enactments of the darkest possibilities of human nature. Yet only recently is a wave of moral indignance among viewers surging over our society. There is a growing unwillingness to acknowledge voyeurism as a common denominator shared by all forms of visual entertainment. It’s a feature of entertainment that prevents any production from sitting atop a moral high horse and declaring its virtue. As a consequence, rather than relegating a small sample of entertainment to the ‘unethical’ pile, the indignation of viewers and critics alike should be levelled against voyeurism inherent in all forms of visual entertainment. Penny Dupuie is absolutely right to point out that ‘True Story’ walks an ethical tightrope. The problem lies in suggesting there is any form of film or television that does not.

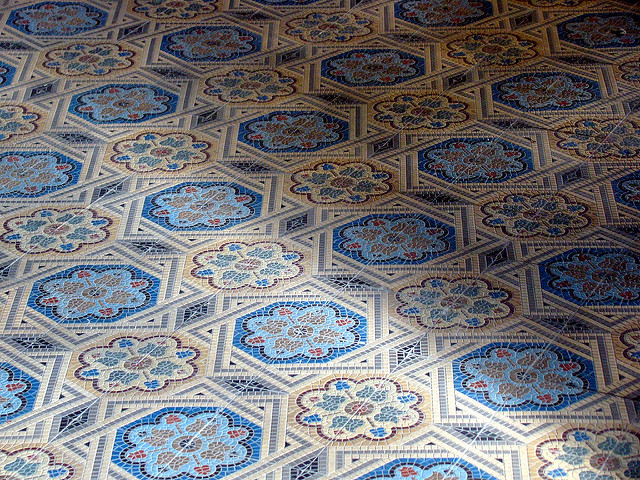

Image by Bradley Fulton