On the Campaign Trail with UKIP

“There’s a woman who uses asparagus to see the future and she knows who’s gonna win.” Jim’s cancerous throat wheezes out this barely comprehensible sentence. It’s three weeks before the general election and I’m having gammon and shandy with a local UKIP faction in the West Midlands. I have spent a hot day watching them canvass the pot-holed roads of this forgotten part of England where they seek to overturn a 15,000 Tory majority. James is the candidate for the local seat; Jim, proudly kitted out in a Walsall strip and a purple rosette, is one of his crack team of leafleters. Hearing Jim’s opinion is not a cue for me to rejoice that my metropolitan preconceptions of UKIP are justified. It is sobering and it is heart-breaking.

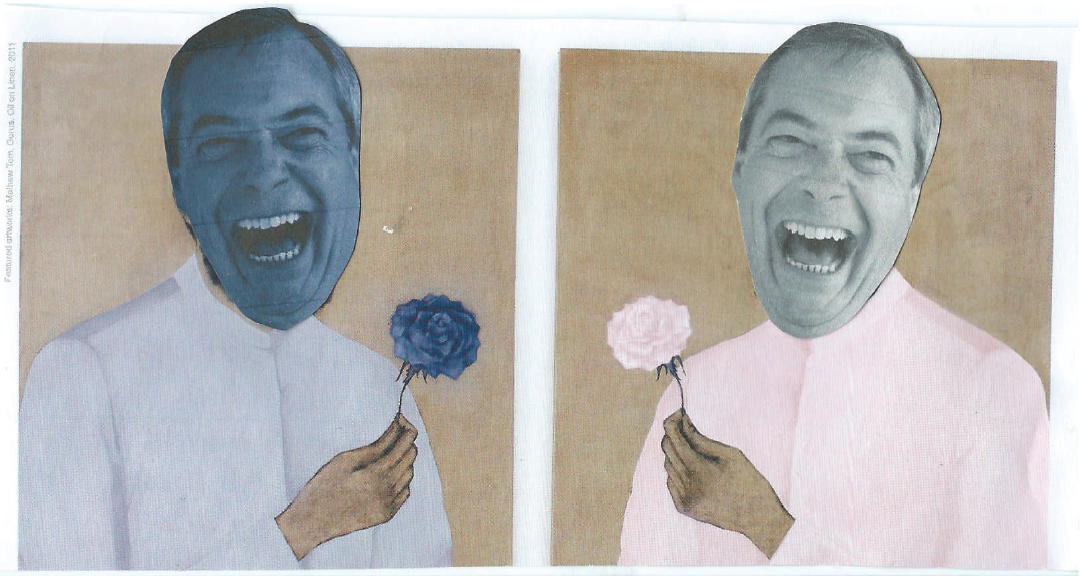

Despite the semi-urban sluggishness of the midday surroundings, arriving into Walsall I am plunged into a hive of UKIP activity. James is negotiating with Steve Crowther, the UKIP chairperson, on his car’s handsfree. “If we could get Nigel just to say something for the loudspeaker I think it would really make a difference.” He is haggling for Farage’s Midas voice to add sparkle to his election day battle bus. Crowther is reluctant to commit the leader’s precious time to this West-Midlands backwater, overlooked by most of the country – and, it seems, UKIP HQ. They continue to talk as we drive through mile after mile of pebbledash to pick up James’ right hand man, Dennis. Dennis is a lorry driver for Jaguar, kept on permanent tenterhooks by a zero-hours contract. I subsequently read UKIP’s manifesto on the subject: “Because UKIP recognises that zero-hours contracts suit many people, we will not ban them.”

James, clad in a tweed jacket and cream chinos, sees Dennis waving his arms at him and pulls the car to a stop. Dennis is morbidly obese but flip-flops with surprising energy into the back of the car. It’s hard not to get carried away by him as he tears my mediocre cricket stats to shreds with his chirpy Brummie affability. The chat turns political after some initial cricketing banter and I chastise Dennis for describing Walsall as ‘Beirut.’ “What is your definition of racism?” he retorts fervidly. I give myself five seconds leeway. “An unsubstantiated fear or…” I begin, but Dennis objects to my pretentious use of ‘unsubstantiated.’ He then jumps topic to explain why educated pockets of the constituency do not vote UKIP. We pop into an office in an industrial car park to rent equipment. Farage’s team is reluctant to commit to the speaker system but Dennis goes ahead and pays £300 of his own money to rent it for two weeks, “Chips or no chips? Chips! One week or two? Two! You see George, I’m the decision maker!”

Dennis rushes off to seize a last-minute shift which has become available at work, and James takes me out of the industrial estates and into the housing estates for some traditional door-to-door canvassing. He locates ex-serviceman Jim, his other trusty assistant who is “mad as a box of frogs.” Jim is hobbling with leaflets along the parallel roads of semi-detached properties. Marking a map stretched out on the car bonnet, James identifies some uncanvassed roads and sends Jim off to recruit in fresh pastures. Some leaflets are then thrust in my direction. James notices my furrowed brow and pompous air of neutrality. “Oh I’m not asking you to vote for us!” he blurts, slightly red-faced from the sun. I agree to carry them but will hand them to James to shove in letterboxes.

We get into a routine. I proffer a leaflet to James, if there is a car in the drive he rings the bell and waits fifteen seconds, if there is not he assiduously posts and moves on. People seem by and large receptive to James’ message which emphasises cutting the foreign aid budget by £8 billion as well as scrapping HS2: a 76-year old who has voted Labour all his life nods vehemently as James sets out his stall; a freight-train driver opens the door scornfully and closes it promising to “have James in mind in the polling booth.” Over the whole afternoon only two people refuse to listen to the UKIP pitch. Time and time again people join James’ criticism of immigration by saying “I’m not racist but…” James notices me scribbling this down and explains that this common refrain is an unwitting double-bluff, that this does indeed prove that they are not racist.

One man rushes across the road to greet James keenly. “Have you got a poster for me to put in the window?” he demands. James says that he does not have any on him but takes down the man’s details in his leather notebook. A couple of moments later he sternly tells me that he will not be following up on what seemed like a prize catch. I ask him why. “He was trying to hide a Nazi tattoo on his right arm. That man gave me the willies.”

Tired from politicking, we get back into the car and drive to a Toby Carvery to buy a well-deserved meal for Jim. James explains his decision to join ‘a bunch of fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists.’ For him UKIP’s naivety is their attraction, “UKIP will have lost its meaning when it is full of political animals.” He says that he left the Tory party because their politics had become cynical vote-grabbing and cites David Cameron’s legalisation of same-sex marriage as an example. I ask him if this amateurishness is enough to be politically successful. James takes a long pause, “Well ‘amateur’ comes from ‘to love.’ We are in politics out of love. We are patriotic.” I point out the St George’s Flag, which flutters appropriately past at this moment in time. Twice that day people have complimented me on my ‘strong English name.’ “The English have a very strong sense of place. When I first came here as the UKIP candidate my neighbour at the meeting told me proudly ‘I love Walsall wood.’”

Pulling off a traffic-heavy roundabout into the carpark, we see Jim, his eyes watering in a perpetual squint. James orders tiredly, “One pint of orange squash, two bitter shandies, and two carvery suppers…George are you sure you won’t have a carvery?” I acquiesce, we take our our plates of deliciously fake beef back to the table where Jim continues a conversation with me, of which I am lucky to understand every other word. I do catch a telling sentence: “Yer see I was bullied at school.” Jim grabs my hand and jabs it against his chest where an abnormal pectoral growth testifies to some horrific injury.

One month and an election later, I manage to extract the telling statistics about James’ constituency from the gizmo-heavy analysis of the BBC. James increased UKIP’s share by 19.6% and came third in terms of number of votes; so did UKIP across the whole of the UK. For these gains they have one singular MP. The voiceless therefore still lack a voice. It’s hard to say whether or not this is a good thing. Neglect can be dangerous; so can the far-right.