Not a Fairytale

There are lots of things I could tell you about Tom but the only one that really matters is that he jumped off the bridge when he was twelve. Because he wasn’t scared, you see. He’s never been scared of anything, not as long as I’ve known him, which is just about forever. Things that other people are scared of just make him laugh. He’s got this big, ugly, cawing laugh, like the sound one of those big, ugly, black birds make, a rook or a crow, I never know which is which. And it’s like that laugh takes all the power out of the thing and shrinks it down so small that it just can’t be frightening, not anymore. That’s how come he jumped off the bridge. He saw the funny side. He wasn’t scared.

It’s how come we’re friends, too. I’m scared of everything. Heights and the dark and speaking in front of people I don’t know and being kidnapped on the way home from school and nuclear weapons and car crashes and global warming and terrorism and walking across the estate by myself on a Friday night and spiders and dying. Dying scares me more than just about everything. It’s funny how you can go fifteen and a half years without ever thinking about a thing, without it ever really existing as a thought at all, and then something happens and suddenly it’s always there like a little black spot at the back of your brain, where you can’t reach it or do anything about it but you’ve just got to know it’s there, ready, waiting, and even when you’ve stopped really thinking about it all the time (which I did for a while after it happened, almost a year – in fact I’ve only really just stopped now) and it’s stopped actually stopping you from doing things, like sleeping and eating and going outside, it’s always there. I like Tom because he has no black spots like that. He doesn’t get hung up on anything, not exam results, or girls, or things in the news, or what people think of him, or what he’s going to do with his life, or what the point is in anything. He just is. And what he is is brilliant and exciting and unpredictable and fearless. That’s why this story is about him and not me.

The other good thing is that Tom doesn’t feel sorry for me. For a while, everyone felt sorry for me, and then most people stopped and instead there was just this sort of invisible red line drawn up all around me, like I was some rare, dangerous animal at the zoo, or a dead body on a crime scene. Something interesting to come and gawp at, but at the same time slightly repellent, the kind of thing you know it’s a bit morbid and gross to spend too much time with, the kind of thing you don’t want to get too close to. With Tom, there is no pity and no red line. The thing is, fundamentally, Tom isn’t particularly interested in me. Or anyone, really. He says he likes me because I’m funny (I can be funny, but I’m less good now) and because I can run as fast as a boy and I’m decent at football and I’m not a snitch and I’m not a slut and (he doesn’t say this but I know it’s true) he knows I will always do exactly what he says because I haven’t got anyone else.

Tom has loads of other people. Loads of friends. Loads of girls. I’m not jealous. One of them, a particularly nasty, beautiful (it always confuses me how nasty people can be so beautiful, you’d have thought all the nasty stuff on the inside would have to start showing itself on the outside in the end) one from last year, called Tara, told me that I was. We were at a party and I think I was watching Tom because I am always watching Tom and she came over to me and told me in no uncertain terms that he was hers and that if I ever tried to touch him with my gross, scabby whore-hands (or something to that effect) then she would fuck me up (again, I don’t remember her exact words, but it was something along those lines). To be fair, she had only met Tom quite recently and she had no idea about me or anything that had happened to me. I remember shaking quite a lot, but when I spoke, I like to think my voice was steady.

“I’m already pretty fucked up,” I told her, cheerfully, “Ask anyone. And Tom and I are just friends. Really, he doesn’t want me and I don’t want him. So I shouldn’t worry.”

I think Tom came over after that. They stayed together for about a month and I was very, very careful when I was around them but very often I could feel her big, blue Barbie-doll eyes boring into me and I had to stiffen my spine and concentrate very hard on looking normal. She broke up with Tom when she realised he’d been sleeping with someone else. It bothered me a bit, when I first knew him, that it didn’t seem to bother him, that he was really totally exploiting these girls, and bullshitting them pretty much every time he spoke to them, and pretending to really care about them when really there were always several on the go at once. I remember having a fight with him about it, possibly the only fight we’ve ever had.

“You can’t do this!” I said, “It’s not fair! You can’t just use people and lie to them. You can’t!” (I think maybe I was crying, or trying not to cry, which is worse. It was when I’d first found him out, you see, and I was quite upset, the way kids get upset when they realise their parents aren’t gods but just flawed human beings, and that celebrities do drugs and stuff, and that sports people cheat.)

“Chill out,” he was grinning, and smoking, and looked profoundly unconcerned, which made me even madder, “Look around you, Kit. Do you really believe in true love? People aren’t meant to just be with one person. There’s no such thing as soul mates. You might as well have fun.” He took a drag and looked at me, brown eyes twinkling. “Life’s not a fairytale, Kit. I thought you’d know that better than most.”

This is another rare gift of Tom’s. He can say things which should be horrifically hurtful but in a way where they can’t hurt at all, they’re just facts. I think I may have argued a bit but I’ve never been good at arguing with anyone and it’s basically impossible to argue with Tom and so I shut up and he offered me his cig and I took a drag and then we were okay again.

Now, it’s just me and him. Out in the wasteland, the bit of dead scrubland behind his house, where people dump broken things they don’t want anymore. We’re sitting in the cab of an old lorry. The main body of the lorry isn’t here – it’s just the front seats, the front wheels. Tom is in the driver’s seat, which he’s pushed back as far as it will go, feet up against the windscreen (the steering wheel has been removed) and still squashed (he’s very tall), drinking a beer and flicking through channels on the radio, which is amazingly still there, blaring out cheesy pop songs and searching for some ‘real’ music. I am sitting next to him, knees pulled up under my chin, smoking, biting my nails, pretending to read a book for school, really hanging on his every word.

“I’m thinking of starting a band, you know, Kit. I fancy myself playing guitar.”

“You fancy yourself fullstop.”

He laughs, his big, ugly, fearless laugh. “True,” he crows, “True.” He takes a swig from his beer can. “But can’t you just see it? I love music, my mate taught me a few chords when I was little, can’t be too hard to get something together. Nick could play drums and…”

“Can Nick play the drums?”

“Well, not yet. But he’d love to. He loves rhythm and beats. Can’t be much to learn, can it, you’re just hitting things with sticks and keeping time and shit.” I can feel him looking at me but I don’t look up. “And you could sing.” I snort. “No, seriously, you’ve got a lovely voice, Kit.”

I look up now, startled. “What are you talking about? You’ve never even heard me sing.”

“Yeah I have. In the shower at my place when you stay over. Sometimes. And in Jake’s car when we were driving to go see that film…”

“We were all singing then.”

“Yeah, but I could hear you. You had a lovely voice. Beautiful.”

I look away. If I cry, Tom won’t know what to do. It’s the only thing he has no idea how to deal with. Crying. So I don’t. I swallow it down and turn back to look at him.

“Thanks mate.”

He grins and squeezes my hand. “No probs, little sis.” Another swig from the can. “Time?”

I glance at my phone. “Nearly seven.”

“Ah, shit. I’m meant to be meeting Nick and the guys.” He downs the beer, throws the can out of the broken window, begins to pull on his jacket. I watch him, arms pulling my legs in closer to me, waiting for my instructions. If he says I can come, I’ll go. If he says nothing, I’ll stay put. That is how it works. I don’t want to push this. My greatest fear, apart from death, is becoming a burden. He’ll ditch me if it starts to be an effort to hang out with me. If I start to get needy. I know he will. I’ve seen it in action. That’s when he ditches his girlfriends.

“I’ll call you tomorrow, yeah?” He’s jumping out of the lorry, ruffling his hair in the wing mirror, lighting up a fag. He isn’t looking at me and this makes it easier.

“Yeah. Sure.”

“Alright then. Later.”

And he’s gone.

He doesn’t call. This makes me irrationally miserable and then angry and then angry at myself for being angry. I sit on the end of my bed, my silent phone in my lap, and stare angrily at my reflection in the mirror. Small and skinny and scrawny as a little boy, wrists very thin, face very pale, spot emerging on the chin, eyes very large and dark and childlike, abandoned. Hair brown, unwashed, a mess. I chopped it all off when I was a bit mad last year and it’s only just starting to grow back properly, and weirdly it’s decided to be curly, like baby curls, like in photos from when I was really little. My hair’s been dead straight for about thirteen years and now suddenly it’s curling again. It makes me look very young and helpless. I’m not a strong person. Not like Tom. I look at the phone again.

“You have no right to be angry,” I tell my reflection, firmly. “He’s not your boyfriend. He’s not your anything. He can do what he wants. You can’t be so dependent. So hung up on him. What will you do if he gets bored of you and doesn’t want to be friends anymore? When he gets bored of you. You know it’ll happen. He’s always getting bored of things. Nothing keeps his attention for long. Why would you be any different? It’s a miracle he’s put up with you as long as he has, really. You’re about as boring as it gets nowadays. You never have anything to say and you never do anything by yourself. So of course he’s bored of you. Of course he is. That’s why he hasn’t called. Why he’ll never call again. Tom doesn’t do goodbyes or explanations or anything like that. This would be the way he’d do it. Just stop calling. Stop caring.”

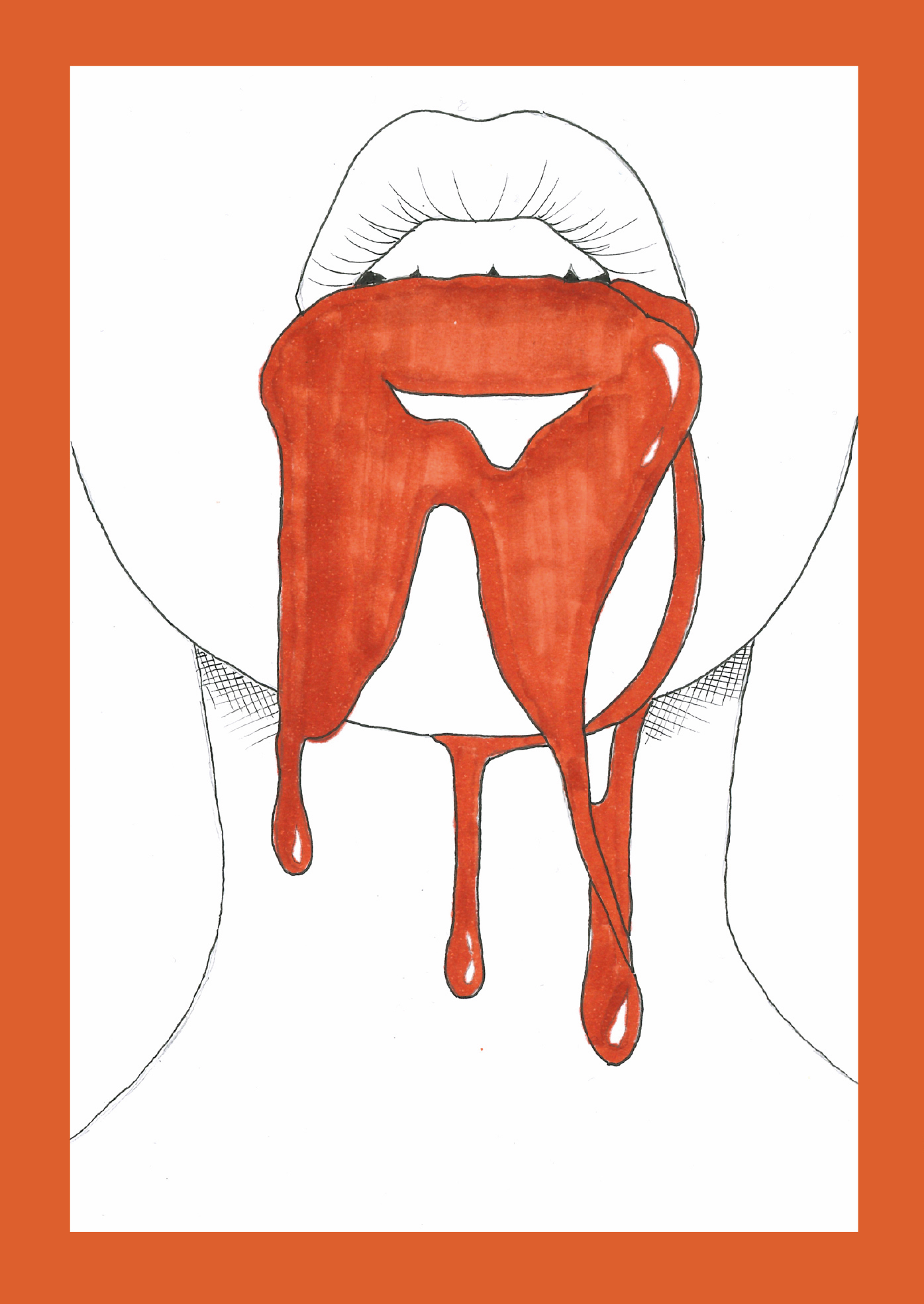

I realise I am close to tears and I bite my lip so hard I can taste blood in my mouth. I look mad in my reflection. Hysterical. I must not be hysterical. I must be calm. I must find something to make me calm.

“He said you had a beautiful voice,” I tell myself. “He didn’t have to say that but he did. And maybe even if he doesn’t want to be friends anymore he’ll still have you in his band. You could still be useful to him.”

I lie back on the bed and shut my eyes. It’s awful to be able to think about things. It’s awful to have so much space in your skull for all this thought to be going on. I think about Tom, standing on the bridge, topless, barefoot, laughing, stretched out from the railings, ready to jump. His dad left when he was two. His mum is always drunk. He never talks about it. Maybe he never even thinks about it. He doesn’t need anyone or anything.

I wish I didn’t need anyone.

The phone rings. It’s Tom’s number. I count to seven. Breathe in. Then I pick up.

“Hey.”

“Kit….Kit is that you?”

It isn’t Tom. It’s Nick. I exhale, very slowly.

“Yeah it’s me.”

“Hey, it’s Nick. Umm…is Tom with you?”

“No.” I’m still struggling not to sound my disappointment. “No he’s not with me. He might be with Amber?” Amber is his current, ‘official’ girlfriend. I don’t mind her because she’s very stupid and doesn’t notice me at all.

“No we’ve tried her…. Never mind I’ll…”

“Wait!” The full implications of the situation are starting to sink in. “Why do you have his phone?”

“He…he left it here. Last night.”

“What happened last night? Why have you lost him?”

There is a long, crackly pause. My voice tautens and I concentrate very hard on not sounding mad.

“Why isn’t he with you, Nick? What happened?”

“Kit, I….I’ve got to go now. It’s okay, don’t worry, we’ll find him. We were just really pissed that’s all, you know what Tom’s like. I thought he might have ended up crashing at yours but…but it’s no big deal. We’ll find him. Talk later.”

He hangs up.

I lie back on the bed again. In itself, this is not a big deal. Tom gets pretty drunk fairly regularly and frequently ends up in unexpected places with no idea how he got there. He tells the most brilliant stories about it all. But it’s strange that he lost everyone. And it’s strange that Nick was so worried. None of the guys are ever really worried about anything, least of all each other. Least of all Tom.

I glance at my phone. It’s 2pm. I’m still not dressed. I haven’t showered, cleaned my teeth, brushed my hair, put on make up, eaten food. I don’t feel particularly like doing any of these things but I know that I should. I go to the bathroom. When I get there, my phone rings again. Unknown number.

I pick up.

“Kit?”

It’s him. Tom. My stomach sinks back to where it belongs in the shock of relief.

“Yeah?”

“It’s me.”

“I know.”

Something’s wrong. Tom normally never shuts up. Now his speech is jerking along like a car on a road full of potholes. There are silences. There are never silences.

“Where are you?”

“I’m…it doesn’t matter right now. I need you to do something for me. Can you do something for me?”

He’s asking. He’s never asked before. He’s told.

“Yeah, ‘course. Anything. Just tell me.”

“I need you to go to my house. To my room. My mum might be in. She probably won’t be but she might. If she is, it’s very important she doesn’t see you. Go in the back door, it’s open, and go straight upstairs. If you think she’s heard you, hide somewhere til she’s gone. She won’t look hard. Then go to my room. You getting this?”

“Yeah, Tom, I get it, but…”

“Under my bed, there’s a box. Just a normal shoe-box thing. I need you to get it out of the house without my mum seeing. If you have to, you might have to climb out the window. It’s easy, I’ve done it heaps of times. You might have done it too, I can’t remember?”

“Yeah, ages ago, I did with you. That time when…”

“Yeah, okay, cool, so you know what to do. You’ve just got to get out of there with the box, okay?”

“Okay. And then I’ll bring it to you, right?”

“No.” I am surprised by the sharpness of his reply. “No, then you take it to the wasteland. Take it to the wasteland and…and bury it.”

“Bury it?”

“Yeah. That’s it. Then just go home and everything will be fine.” A pause. “Police might come round to yours later. Probably won’t but it’s best that you’re prepared in case they do. Don’t panic or say anything stupid. They might ask about me and Nick and Josh and some of the guys. If you know us and how you know us and if you saw us last night. Stuff like that.”

My heart is beating very fast. “What do you want me to say?”

A pause of a fraction of a second. “Just the truth. Just tell them you saw me in the afternoon but I was gone by seven. Say you didn’t see any of us last night. Don’t stress about it. Just say that. It’s the truth and they won’t push you on it. It’ll be pretty routine. Just…just don’t mention the box, okay? If they ask where you’ve been, say you went to the shops. Buy some milk on the way back, just in case. Okay?”

“Okay, Tom but I can…I mean, I would…if you wanted me to, I’d say…”

“I know. But you mustn’t. Christ, I know I’m not the greatest but do you really think I’d ask you to do that for me, Kit?” He sounds genuinely hurt. “I feel bad enough about this.” Another pause. A cough. “Anyway, Amber’s saying I was with her.”

“So it’s okay for her to lie for you?”

“Oh shut up, Kit, for once in your life. I’m doing the right thing by you okay? I’m keeping you out of it. Just the box, okay? Just get the box and get rid of it. And…and this phone. I’m sorry, but you’ll have to get rid of the phone as well. Break it and bury it with the box. Nick and I have both called you now. It’s too risky. If the cops ask, tell them you don’t have a phone. They’ll have seen your dad by then, they’ll believe it.”

Things that hurt. Things that hurt that he won’t let hurt. Only that one did. He’s losing his touch. He’s impatient. He’s worried.

“Okay.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yeah, ‘course. Get the box, bury the box. Even I can do that.”

“I owe you. I’ll buy you a new phone. A better one than that piece of crap.”

“An iPhone?”

“Don’t push it.”

Another pause. A safer one.

“So you’ll go now, yeah?”

“Yeah.”

“And Kit?”

“Yeah?”

“Please don’t look in the box.”

Strange how I can be scared of so many things and yet now, now that I have no choice, I’m not scared at all. I slip in the back door of Tom’s house, very quiet. I know immediately that his mum isn’t here. If she were here, I would hear her talking to someone (she can’t be alone) or snoring, passed out on the sofa in the living room. So I’m okay.

Even so, I concentrate very hard on being as quiet as possible as I get up the stairs and cross the landing and push open the door of Tom’s room. It’s a dump, as usual. I drop to my stomach and reach out under the bed. My hands close around dirty magazines and packets of cigarettes and old clothes and, finally, the box. It had been pushed right to the back. Battered shoebox, two elastic bands keeping it shut. I pick it up, stuff it inside my coat and, even though I’m pretty sure I don’t have to, leave via the window. I remember the time we snuck out when we were about thirteen years old. It was the middle of the night and his mum was shouting and smashing things. We were giggling so much by the time we got to the ground that we fell down and clutched our stomachs and just lay there for about five minutes and he put his hand over my mouth to shut me up.

I’m very calm by the time I reach the wasteland. I’m fine when I have orders, when I know what I’m doing. I slip through the hole in the fence and find a nice dirt patch somewhere near the back, where the earth is loose, and I get down on my knees and dig with my hands. As I dig, it begins to rain, a steady, miserly, miserable drizzle, and the dirt softens in my hands.

I put the phone in first. I quite enjoy snapping it and stamping on it. It’s weirdly therapeutic. Then, I look at the box.

I trust Tom. I trust him instinctively and completely. I do what I’m told. And he told me not to look in the box.

The bands come off easily. I snap one of them. My heart is thudding and for the first time since Tom rang, I am really, terribly scared. I take off the lid.

It’s a gun.

Of course it is. As soon as I see it, I know that I knew all along. Strange, how I’m no longer scared, now that I hold it in my hands. Strange how my heartbeat slows to regularity again. Strange how I can put it back, calm and cool, back in its coffin, and shut down the lid and cover it with earth. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. The funeral I never attended. It is safe now. He is safe now.

I am ready for the police but they do not come. I go back to Tom’s house from the wasteland and clean myself up and borrow one of his mum’s jackets and put on some of her make up. Then I go to the supermarket and buy milk and a big bar of chocolate. Then I go home and there is no-one there, so I put the milk in the fridge and then I go upstairs and shower and put on some clean clothes and do my make up again and my hair and then I pick up a book and go downstairs and put on the TV and I eat the entire bar of chocolate, square by square, and I don’t taste a mouthful. Then I go upstairs to the bathroom and throw up.

I wait and wait all day. I wait for policemen, or for one of the guys, or for somebody’s mum. I wait for the world to fall apart. I do not wait for Tom. I would not know what to do with him anymore. I do not know what I should do.

I guess I fall asleep some time because when I wake up it’s the morning. The TV is still on. I flick through channels and wait for the local news.

I do not have to wait long. It is the first story. A local school boy has been shot dead in what appears to have been a gang fight, under the flyover, around 2am night before last. No witnesses apart from the boys themselves. Suspects called in for questioning. The police discovered the body last night. The boy’s mum had reported him missing earlier that day. The police hadn’t been taking it too seriously, until workmen found blood on the pavement under the flyover. Then the police had gone down and seen it was the traces left by a body that had been dragged, bleeding, off the road, through a hedge and a piece of shrub land, into a ditch.

He was sixteen. Harry Adams. I knew him. I ate pizza on his fire-escape once. He had a dog called Herbie. I sat next to him for a year at school. In maths. He’d been very good at maths.

I think I’m going to be sick again, but then it passes. I turn off the TV. I sit in silence and try to remember how to breathe properly.

I have to think. I don’t want to, but I have to. And I have to be brave. For once, I have to be brave. There is no-one left to tell me what to do. I smashed my phone. I’m entirely alone and I have no idea what to do. But I have to. I have to know.

I go to the police station.

It is strange to see him like this. So very small, smaller than me, more fragile than me, hunched up on the bench in the police cell. His eyes huge and flat and defeated. He looks up at me. Because I’m tall now, I’m towering over him, and I have all of the power. That terrible, wonderful thing that had bound me to him so tightly I thought it would never let me go, has come undone, unravelled into a little, insignificant heap of broken threads. I am no longer his and it was I who chose, not him, in the end.

“You opened the box, then?”

I wait. I do not have to speak. I do not have to do anything.

“Do you think I did it?”

“You had a fucking gun under your bed.”

“I know. I know what it must look like…”

“No you don’t. You don’t know anything.” I’m starting to cry and I can’t stop myself. I realise that it has been a very long time since I cried and there must be a lot of tears ready and waiting now. I wonder if I will ever be able to stop. “He was our age. He had a mum. He had a little sister. He was a kid.”

He’s crying now too. I’ve never seen him cry.

“I didn’t do it, Kit,” he’s whispering and his eyes are all shimmery and strange, “I don’t expect you to believe me but…I swear I didn’t.” I wait. “I had a gun. We all had guns. Josh’s brother’s got a mate…I don’t know…I guess we thought it’d be cool.” He sniffs. “But I never fired it. I swear. I didn’t even have it with me that night. It was just a fist fight and then…. I didn’t even know what had happened til later, none of us really thought…”

“Who killed him then?”

“I…I…”

“I know you know.”

He looks desperate, like an animal. “I…can’t tell you. I…I couldn’t…”

“You’ve got some pretty interesting ideas about loyalty.”

“Kit, please…”

“No. I’m done with you. You’re bullshit.”

“Kit, you have to believe I didn’t do it. Even if no-one else believes me, I can’t live with the idea that you think…that you think I…”

“I don’t believe you did it.” I say the words slowly, steadily. “But I believe you could have done. I don’t think there’s anything you couldn’t do.”

A policewoman opens the door. “You’ll have to step out for a minute, love. His mum wants a word.”

Tom groans. “I can’t see her. Please tell her…”

“She’s your parent, you’re a minor, she has a right,” the policewoman says firmly. Then, to me, “Follow me, please.”

I look back at Tom. We both know that it will be the last time. I wait for the memories and the tears to rush and flood me but there are none.

“She can stay,” Tom says, desperately, gesturing at me, “Mum won’t mind.”

I smile at him. “I used to think you were the bravest person in the world,” I tell him, “I used to think you weren’t afraid of anything. But you’re a coward. A coward, a coward, a coward.” I relish the word, the word I have only ever used against myself, or my reflection. “Now talk to your mum. Because you fucking have one. Because you may not like her very much but at least she loves you enough not to kill herself.” He winces. I’ve struck home. I’m glad. “You were supposed to look after me.”

And then I leave. I just go. The door clangs shut behind me.

I go to the wasteland again.

This is where I belong, I think, and in thinking it, know it to be true. After all, there is no other place, nothing and nowhere but this, where the wreckage of the world washes up and waits. Broken things. Unwanted. No use. I walk through it all, like the last survivor of a bombed out city. I walk as though I am looking for something, as though there is something to be found. Something to be taken back.

I don’t realise where my feet are taking me until it is too late. I am going back to the scene of the crime. To the place where I buried the gun. It’s alright, though. A new load of junk has been dumped this morning and it covers it. There is nothing to see.

I sit in the cab of the lorry for a bit. Turn on the radio. Just for something to do. I don’t hear it, I just let it exist. Somewhere in the background, unreachable, undeniable. Music. There it is, ready, waiting, the indelible spot at the back of my brain.

“You’ve got a lovely voice, Kit,” he said.