The Return of the Prodigal Son? The Creative Potential of Violence Re-Examined.

The 20th century was the century of violence par excellence. People were killed on a larger scale between 1914 and 1990 than ever before. Treblinka and Kigali, Stalingrad and Sarajevo: the sites of these atrocities retain a dark and ominous prominence. Isaiah Berlin was moved to write: ‘I remember it only as the most terrible century in history’.

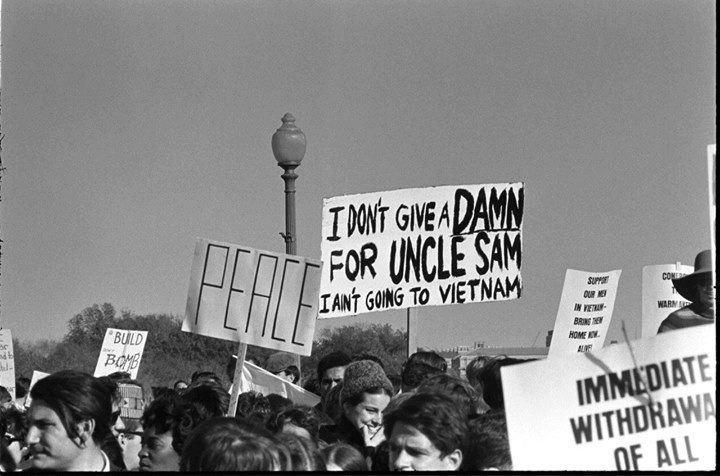

Yet it is important to try to demythologise violence. Violent protest did not always carry the stigma of menace and insecurity that it does today, a stigma evident in the widespread condemnation of student protesters at the Millbank Tower in November 2010 as selfish and unjustifiable. Many student radicals of the 1960s thought of violence as a means of achieving liberation, a means of questioning what the New Left intellectual Herbert Marcuse termed the ‘containment of social change’.

It was the Algerian War of Independence that best exhibited the power of violence when used by the oppressed to achieve liberation. As Jean-Paul Sartre wrote in his Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960), ‘in certain circumstances, a group emerges à chaud and acts where previously there were only gatherings’.

Certainly, in places like Algeria and Vietnam there was this community à chaud. These revolutionary communities used violence to reestablish their liberty. More than that, they were using violence to bring about their recreation. Frantz Fanon, a French-Algerian psychiatrist and philosopher, who worked in the hospitals of Algeria, “At the level of individuals, violence is a cleansing force. It frees the native from his inferiority complex and from his despair and inaction; it makes him fearless and restores his self-respect.”

Sartre echoed this sentiment in his preface to Fanon’s Les Damnés de la Terre, a psychiatric analysis of the effects of colonisation, writing: “This irrepressible violence is neither sound and fury, nor the resurrection of savage instincts, nor even the effect of resentment: it is man recreating himself.” Student leaders drew inspiration from the kind of activity ongoing in the Third World.

Parisian law student Tiennot Grumbach, recalled how between 1962 and 1965 he “organised a [youth] camp at Sidi Ferruch [near Algiers] through which all the young people who made ‘May ’68’ passed”. Anti-colonial violence in the Third World was beginning to inform the activities of First World student protest.

The Third World could no longer be purely limited to a geographical constituency. It came to be a by-word for combating oppression. And that oppression existed even in the most privileged of societies.

In 1964, Malcolm X stated, “I am for violence if non-violence means we continue postponing a solution to the American black man’s problem just to avoid violence.” In 1966, the Black Panther Party was formed. This was a demonstration of the ways in which violence could be employed on behalf of the ‘internal colonies’ of the First World. Violent political change was internationalised.

Violence was also re-interpreted as a powerful phenomenon in the European past. Numerous allusions to the creative violence of the French Revolution were made in the wake of the Algerian Revolution. Ferhat Abbas, the Algerian independence leader, warned the French authorities that “the world, as in 1789, is experiencing a revolutionary epoch.”

The term ‘Third World’ was first coined as an allusion to Abbé Sieyès’ 1789 tract ‘What is the Third Estate?’ Compare Sartre’s “group à chaud” to nineteenth century theorist Alexis de Tocqueville’s description of the 1789 revolutionaries – people who “followed [their] own convictions boldly, passionately… a time of inexperience doubtless, but of generosity, of enthusiasm, of virility, and of greatness, a time of immortal memory”.

Violence must not be exalted, nor celebrated as an end in itself. But the modern distrust of violence is dangerous. In his 1952 work, Black Skin, White Masks, Frantz Fanon argued that “man is a yes; I will never stop reiterating that. Yes to life. Yes to love.”

Fanon’s violence was driven not by hatred, but by a compassion and sense of justice. That compassion promoted freedom and equality and fraternity. Violence demythologised was merely a means of expressing a lack of these: for ‘man is also a no. No to scorn of man. No to degradation of man. No to exploitation of man. No to the butchery of what is most human in man: freedom’.

Perhaps the time has come to reconceptualise violence: its power as a force for social change, its potential for expressing compassion as well as hatred, and most importantly, its use as a means of venting profound opposition to oppression.

Image by Yana Lozeva