Women of Allah: An Interview With Exiled Artist Shirin Neshat

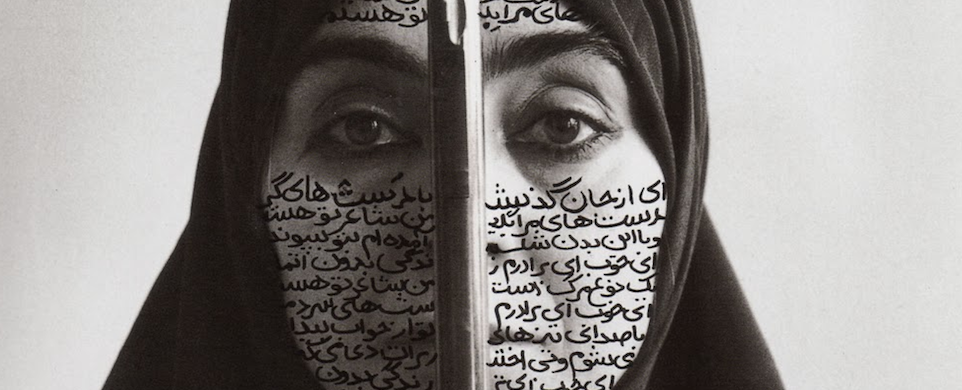

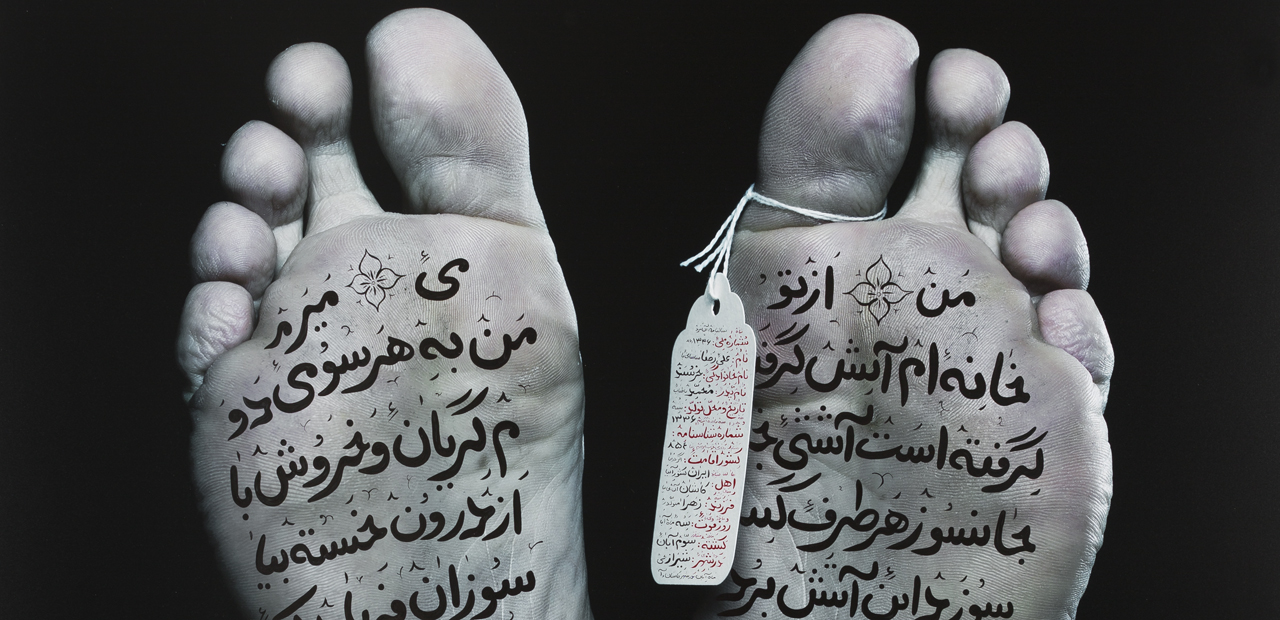

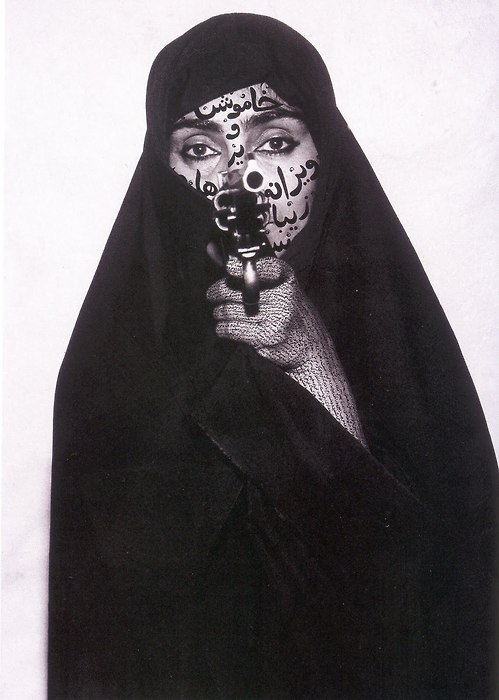

The figures in Women of Allah, Shirin Neshat’s collection of early photographs, are at once modest, seductive and actively aggressive. Veiled Iranian women have their exposed flesh overlaid with the elaborate script of Farsi feminist poetry, their eyes aligned inches from the barrel of a gun, or their hands stained red with the blood of martyrdom. Like the decades’ worth of controversial and challenging visual art that followed them, these four monochrome portraits unpick the paradoxes of female Islamic identity and the flaws in Western perceptions of it.

Neshat’s photography and films navigate the intersection between art and politics, East and West, masculine and feminine. Named “Artist of the Decade” by G. Roger Denson for The Huffington Post in 2010, she has received international acclaim, but she is very clear about the politics of her artistic motivation. Recently she explained that, as an Iranian, “an artist like myself finds herself in the position of being the voice, the speaker of my people…art is our weapon, culture is a form of resistance.”

Born in 1957, Neshat grew up in Iran before leaving to study in Los Angeles prior to the 1979 Islamic revolution. She has described her subsequent return, nearly twelve years later, to her homeland under the theocratic regime as “one of the most shocking experiences that I have ever had.”

“I think that a lot of us take for granted the importance of democracy [in the West.] I remember when I was detained in the airport in Iran and I was just terrified because I was aware that I had no way of defending myself.” It is the daily reality of living without democracy that explains why “every Iranian artist, in one form or another is political. Politics have defined our lives.”

In her 1998 video installation Turbulent, two parallel screens are set up in dynamic opposition: on one we see a tensely static audience of men, symbolically partitioned off from the other screen where a lone woman sings in an empty auditorium. Her haunting voice builds our frustration to almost unbearable heights, made more unbearable if the watcher remembers that in Iran today it is illegal for women to sing in public. The figures on the screen pulse before us and we sense their ache to break free from sexual repression. Yet her passionate political criticism is profoundly defined by her Iranian identity. She doesn’t visualise the smashing of the partition in Turbulent; she doesn’t shed the modest veils of her sitters for Women of Allah.

“In Iran,” she tells me, “you don’t even know a way of expressing yourself without self-censoring and working within the parameter of the absence of freedom of expression. We have learnt to be very poetic, and symbolic, and metaphoric in terms of forming an expression. My aesthetic is automatically very safe, in a way, as it gets diluted in poetic language so that the government may not be able to detect the sharp knife.”

Yet Neshat argues that this “has actually empowered artists because they have to be so inventive and savvy to find ways to threaten the government.” She cites the example of a recent Iranian production of Hamlet which veiled its implied criticism of the government so subtly that “whilst every Iranian in the audience understood the politically subversive message, the Head of Censorship for the government didn’t even understand why he’d been sent to look at it.”

If her art is a weapon, however, it is targeted as much at the prejudice she encounters in exile as at the oppression she confronts at home. “I am blown away by the West’s misunderstanding of Islamic values and culture. The Western notion of the superiority of their societies and their need to import their ideas into Eastern societies that they consider more or less barbaric is very arrogant and misperceived.”

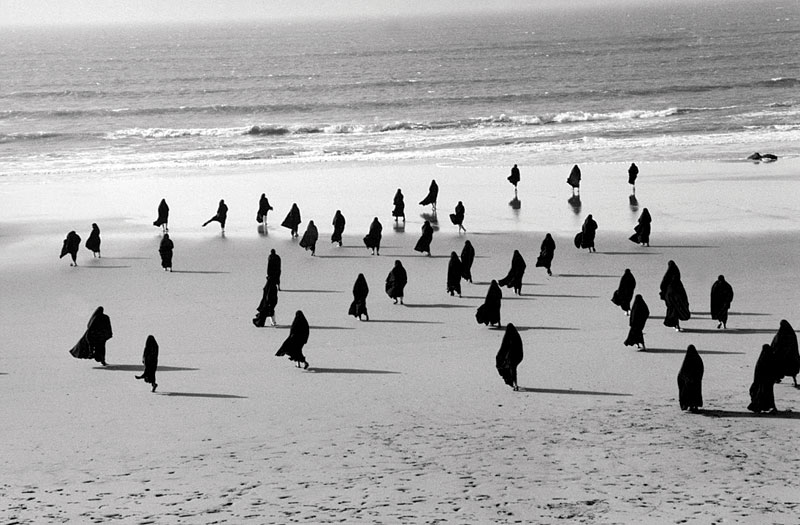

In particular, her work addresses the failing of western feminism to appreciate the nuances of women’s lives under Sharia law in Iran. The group of women who progress through expanses of dust-blown desert to the ocean in her video instillation Rapture are not merely oppressed and isolated: they are vigorously resilient. Together, they launch a boat into the crashing waves, their faces emphatically individualised beneath their dark, ubiquitous veils. Neshat’s art invokes the reality that today “there are more Iranian women educated in university than men. Women have become the biggest threat to the government.”

Her first feature film, Women Without Men, won her a Silver Lion at the Venice Biennale in 2009. It was a magical realist exploration of the 1953 CIA-backed coup d’état in Iran which imagined four women’s search for meaning beyond male governance. The women evoke a diverse range of female experience in Iran, from the restless housewife to the prostitute, but together they escape the violent streets and gather in an orchard of mesmerising lushness and mystery. She poignantly describes their solace in each other’s companionship, in their own female, Islamic “homosociety”, as theorist Eve Kosofky Sedswick has termed it. As stereotypes of submissive Islamic women are subverted, she demonstrates how, as she once explained to the journalist Collier Schorr, these women’s “protests are manifested in subtle yet powerful ways” – ways akin, perhaps, to her own artistic statements.

Yet her art aims, through its subtlety, to incite more vigorous, explicit protest. In the year that Women Without Men was released, Iran’s Green Movement flooded the streets of Tehran with the same cry for democracy that the film highlights in the protests of 1953. Her strong female protagonists were being mirrored by modern-day women rising to the forefront of the demonstrations.

It was the role of women in the Green Movement, and later in the Arab Spring, which Neshat found most inspirational. The female protesters were “women who were educated, forward thinking, non-traditional, sexually open, fearless and seriously feminist. Iranian women have found a new voice and their voice is giving me my voice.”

“One thing that I have learnt from the Arab Spring and the Green Movement – and I actually took part in one of the big demonstrations in Egypt – was that the people’s power is quite amazing. For the first time I became a strong believer that change could only come if everyone, absolutely everyone gets out on the streets. Nothing is more frightening to the authorities than sheer numbers of people. They cannot kill enough, they cannot arrest enough, they cannot censor enough, there’s just nothing they can do. The sense of hope becomes very contagious – it doesn’t matter if you’re rich or poor, or educated or not, or young or old…In the Green Movement there were people who never in their lifetime thought that they would get out on the street, and they were talking about it.”

Neshat remains devoted to her political mission as an artist; she has exhibited ten times so far this year, to audiences worldwide, from Seoul to Budapest. Despite the thousands of miles which have separated her from Iran for decades; despite the fierce censorship of the Islamic regime who brand her work “Anti-revolutionary”; despite the frustrating disconnect between East and West . Or perhaps it is because of all these things; and because she still has hope in the global fight for democracy.

“People think that the Arab Spring and the Green Movement have finished because of the lack of protest, but opposition doesn’t happen only in the form of physical demonstrations, a lot can be done off the streets… And now when we ask people if there’s anything going on underground, they say, “Of course there is, it’s all really hidden but the genie is out of the box.”

In exile, she continues to keep the genie alive.