The Drugs Don’t Work: Rethinking Lethal Injection

“I feel my whole body burning”. These are the last words of Michael Lee Wilson, 20 seconds into commencement of execution by lethal injection in Oklahoma, USA, on the 9th January 2014. Wilson’s intended last words were “I love everybody. I love the world. Love my daughters for me. I’m going to miss you always”. But then he felt his whole body burning, and was able to communicate that fact before the paralytic agent of a three-drug cocktail took effect.

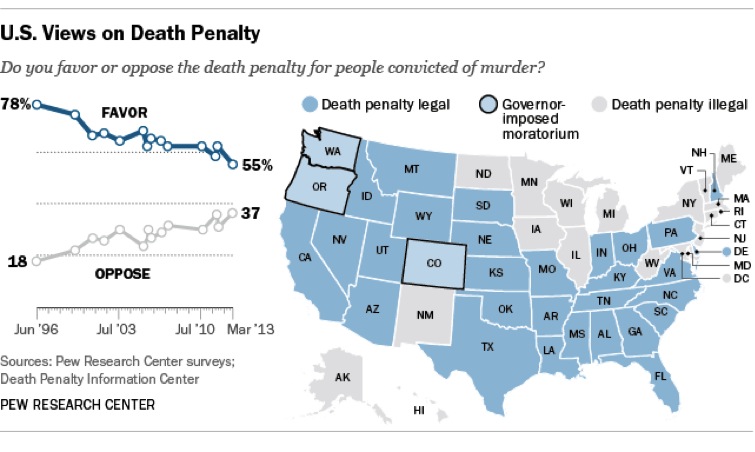

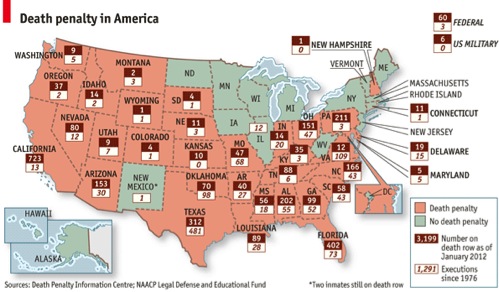

Wilson was sentenced to death for beating a shop employee to death with a baseball bat during a robbery. There have been 1,196 executions by lethal injection since 1976, when the death penalty was brought back into practice in the US after a four year abolition. Before 2010, a three-drug cocktail was standard: an aesthetic, paralytic and a dose of potassium chloride to stop the heart. You’re strapped to a gurney by your feet, legs, chest and arms. Two intravenous lines are inserted. The drugs are administered. All very clinical. Except that you might still be awake – paralysed, no one would be able to tell — but awake – according to post mortem examinations that found 88% of inmates did not have high enough sodium thiopental concentrations for surgical anaesthesia, and 43% low enough for sensory awareness.

Let’s jump back a little bit. Let’s take a look at who gets sentenced to death. Who ends up on that gurney with potassium burning through their veins. Some race stats for starters – 34% of executed defendants are black. Nationally, around 50% murder victims are white. But 76% of executed defendant’s victims are white, and in Louisiana, you’re 97% more likely to be sentenced to death for murdering a white victim than a black victim. Poverty determines your lawyer. “The constitution guarantees the right to an attorney. It doesn’t say the lawyer has to be awake”, to borrow the words of a Texas trial judge. Or your lawyer could be fresh out of law school, or have never worked on a capital case before. You might not have upwards of $25,000 for a competent criminal defence lawyer, and that’s just tough.

A district attorney might, to be elected, want to appear “tough on crime”. They’re going to seek death, as a political statement (just as US politicians supporting the rise in supermax prisons is a political statement rather than a response to some new breed of super-tough criminal). It’s mostly rural southern states who actively maintain capital punishment, and they are generally Republican-leaning. Of course, this depends on the budget of the county. They’re not going to seek death if it will bankrupt them, after all. If they do seek death, it’s imperative to get a “death-qualified” jury, and this can take months. These juries aren’t picked at random; every juror must consider themself able to sentence death to serve.

Next up on the whistle-stop tour of arbitrariness is mental illness. Figures range, but a conservative estimate of death row inmates suffering from mental illness is around 10%. It’s thought the problem will boom as troops back from Iraq Afghanistan commit offences under PTSD. You’re going to be on death row for an average of 178 months: that’s over a decade. You’ll be in 23-hour solitary confinement, and you will probably develop a whole host of mental problems down to that. Despite Atkins v Virginia, which prohibits execution of the intellectually disabled or mentally ill, you may well still be executed – just look at the cases of John Ferguson, executed in Florida on 5th August 2013. He believed he was the “Prince of God”. Then there’s Bobby Woods, who sent the letters from his attorney to his mother, because he didn’t understand what they said. He was executed on 3rd December 2009 after an appeal based on his low IQ failed. Thomas Andre is schizophrenic and has removed both (and eaten one of) his own eyeballs since murdering his wife and two children. The prosecution is still seeking death.

The 8th Amendment prohibits “cruel and unusual punishments”. Let’s be clear here: judges do not base this on 17th Century perceptions of cruelty. Since Trop v Dulles in 1958, the Supreme Court has made clear that what constitutes “cruel and unusual” is subject to “evolving standards of decency”. The arbitrariness of capital cases and the unknown effects of execution methods beg the question: what exactly are the United States’ “standards of decency”?

Dennis McGuire’s execution on 16th January 2014 in Ohio was an experiment. It was the first time use of a two-drug cocktail of midazolam and hydromorphone, and appeared to produce ‘air hunger’. Since 2010, death penalty states have delayed executions to find new drug sources, as the European crack-down on the export of torture goods destined for the US has taken effect and drug companies pull out of the market or refuse orders from the US Department of Corrections. Compounding pharmacies, which tailor-make drugs for patients’ needs, do not have to register with the Food and Drugs Agency, and some will supply states with drugs for execution. Six states have used or intend to use compounding pharmacies to source their drugs, but naturally, pharmacies want this hushed up. Recently it emerged that an official from Missouri travelled to Tulsa, Oklahoma, to secretly pick up $11,000 worth of pentobarbital in person. The Tulsa supplier thn backed out of the deal. Without knowing where and how drugs are produced, these new drug cocktails are literally experiments. Michael Taylor was executed in Missouri in February using drugs from an alternative unnamed source, after a failed battle for an appeal case. We can’t ask him how it felt.

The US may well be running out of options as drugs for lethal injection become increasingly scarce, expensive and controversial. Ohio has stayed the case of the next inmate up for execution, while the McGuire case is queried. States will see more and more delays as drug supplies dwindle. Maryland had not executed anyone for seven years prior to abolishing the death penalty in 2013, due to the controversy on drug protocol. Washington’s governor issued a moratorium in February to suspend executions, claiming he was “not convinced equal justice is being served”. On the other hand, Chief Justice John Roberts’ standards of “cruel and unusual punishment” are not encouraging. In Baze v Rees he claimed that litigants against lethal injection will have to show both that there is a substantial risk of pain, and that this pain could be avoided by a feasible alternative method of execution. States such as Florida and Virginia are litigating for the electric chair to become the default executional method if lethal injection is declared unconstitutional. It appears that if you haven’t got a better option, any method will suffice. With over 3,000 inmates on death row across the states, this is an issue that could see all hell break loose when the drugs run out.