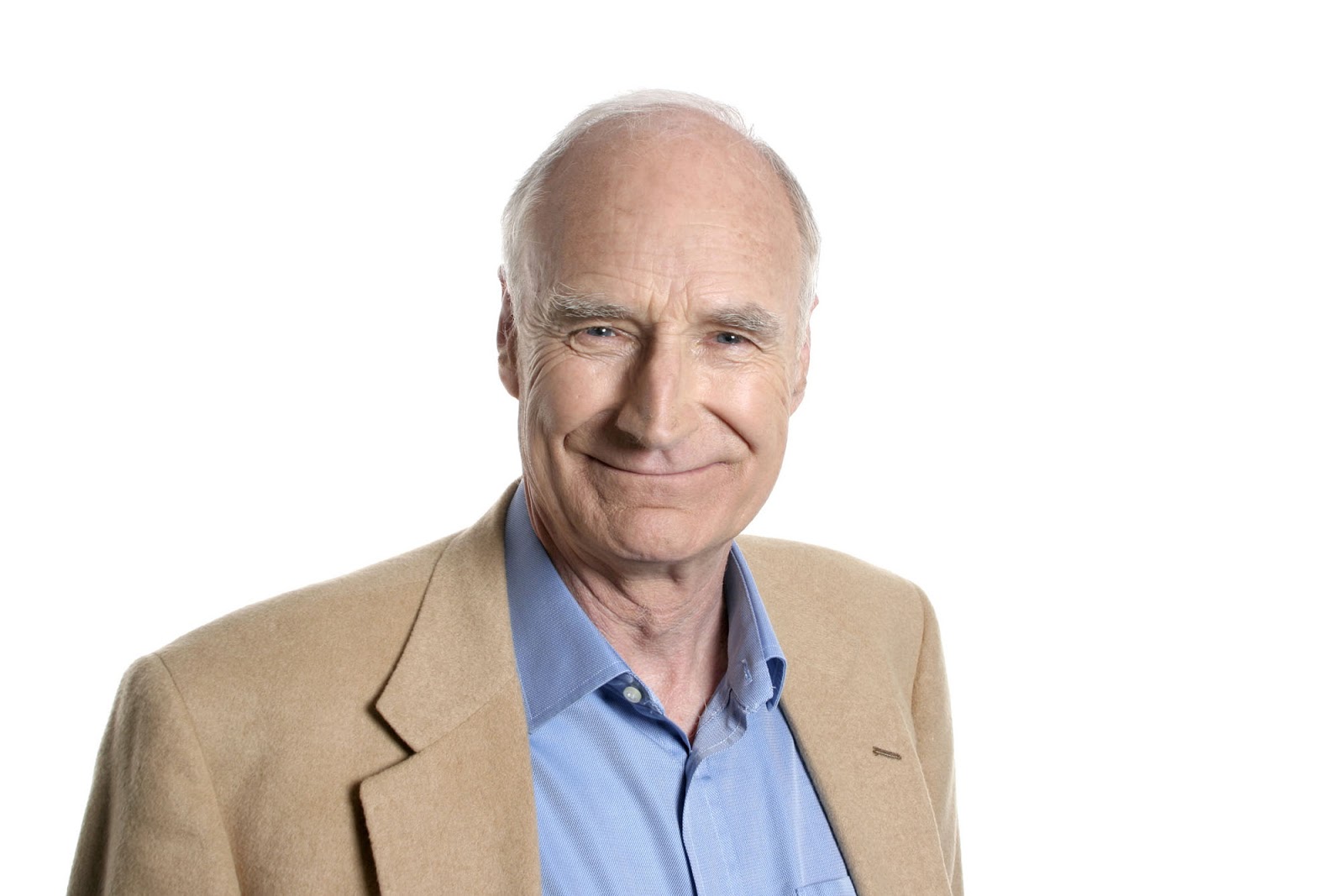

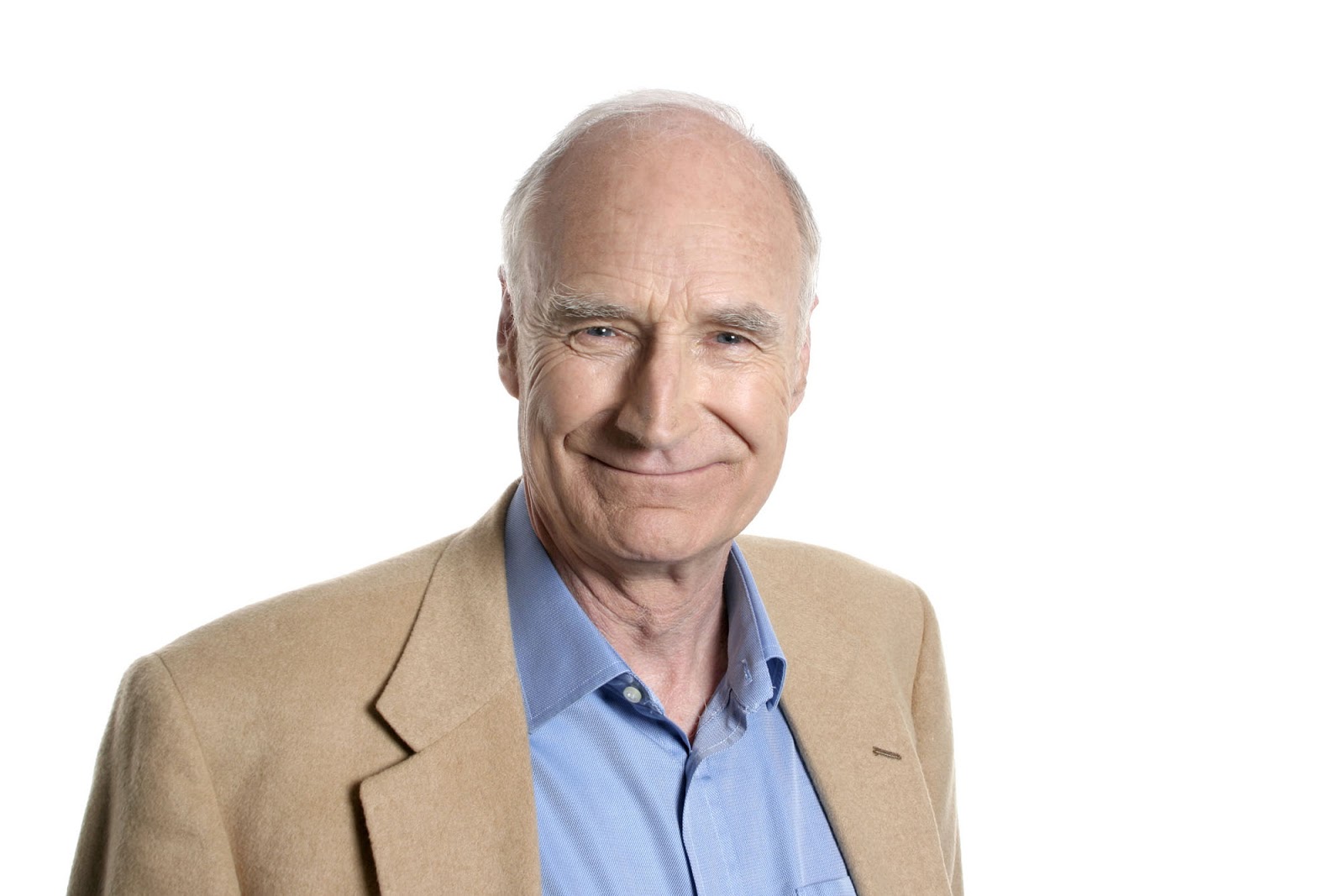

In conversation with Peter Snow

A “complete accident” of a journalism career did not mean a final farewell to theatricals for former Oxonian thesp Peter Snow. A string of decades spent broadcasting with ITN and the BBC lodged him in British hearts as the sprightly presenter with swinging windmill arms and a penchant for props. Though this Balliol graduate’s stagecraft had been demoted to “a bit of fun on the side” after he took up a (supposedly interim) post as a news writer, his inner performer comes to the fore as he gives a whirlwind tour of his recent book When Britain Burned the White House.

Snow’s narration of the 1814 confrontation that saw British forces set fire to Washington D.C. is one of many off-screen projects. His decision to devote a book to these turbulent months sprang from his surprise at the remarkable episode’s obscurity on first hearing about it several years ago, despite its outcome having inspired America’s national anthem. Analysis and anecdotes are peppered with a typical dash of humour: “That was the low point of the special relationship.”

The author’s admirable impartiality in describing how Admiral Cockburn and British troops invaded President Madison’s home and devoured a dinner laid out by the then-runaway First Lady seems almost at odds with his tendency towards showmanship in literary festivals. Snow responds that jingoism might pique interest in his high-speed version of events for such audiences,, but he actively sought balance for the written account. Nonetheless, his publication is a lively affair, with hints of affection for individuals across both sides of the Atlantic – from the “swashbuckling privateer” of the American navy, Joshua Barney (incidentally, claimant to a kiss from Marie Antoinette), to Madison’s wife Dolley who “wrought havoc with the hearts of Quaker lads.”

Alongside the undergrad drama scene, Snow oriented his Oxford days around his Classics degree. An optimist to the core, he refuses to condemn rising university fees but instead describes a degree as “a launchpad to a life where all options are open”. In light of his years covering various wars professionally as a journalist, documentary presenter and author, it comes as no surprise that studying ancient warfare was a particular favourite amid his lecture timetable. In an attempt to divert attention away from my far inferior knowledge about Trajan’s exploits in Romania, I wonder aloud at the spark behind Snow’s military interest. With some pride, he brings up his grandfather, Sir Thomas D’Oyly Snow, a WWI general in the Somme who “took a great deal of stick for the disaster that happened there,” before also paying tribute to his British army officer father. Paired with Snow’s own period of National Service, this soldierly backdrop to his formative years ingrained the military as a lifelong theme. He dismisses the idea that his war experiences could have steered him towards pacifism: “In the last resort, war in self-defence is preferable to subjugation and deprivation of liberty.”

Snow’s professional neutrality was inevitably honed during his news correspondence on the twentieth century’s major wars; he mentions the Falklands, the First Gulf wars, the Yom Kippur war and the Vietnamese first defensive over the course of the conversation. “It gets ingrained in you very early on that you’re there to be dispassionate,” Snow explains. He is keen to emphasise that journalism is less about pushing one’s own opinions, and “more about trying to explain, like a signal-box,” rejecting the current climate of negativity surrounding the press. “It makes terrible mistakes and a host of injustices but its overall benefit to society is that nothing is sacred, and that’s good”. His debut at ITN was not, however, the result of any long-term plan, as he frankly admits: “If I’d been offered a job by The Telegraph I’d probably have taken it,” perhaps reflecting a happy-go-lucky approach held by roving graduates both then and now.

Since partnering with Paxman on Newsnight, Snow has also served as the other half of a successful collaboration with his son, Dan , for several documentaries. Starring in many a GCSE history lesson, this father-son duo’s Battlefield programmes gave Snow (senior) the opportunity to revisit some of the wars on which he reported as a journalist: “To be able to take time and look at sources is very exciting and so much more rewarding, because you can take time and get it right.” Given the swap from news reports to documentaries and books, I ask whether another shift might be in the pipeline – historical fiction perhaps? Snow shakes away the prospect: “I’m too steeped in the effort to get to the truth of things to attempt the counterfactual and the fiction – fun though that might be!”

Regarding his own luck in the world of work, Snow glows with grateful enthusiasm, and sees himself as nearing the stage of having achieved all his goals after “a life full of adventure and rewarding output in all sorts of fields and travel.” Ever on the move, our interview begins only once Snow’s wife has eased his worries about the possibility of Christ Church locking their gates on his parked car. Fearless in the advance of army tanks, this middle-class motorist seems to all but quiver at the notion of being trapped in a car park.

At 75 years old, Peter Snow is a man without bounds – and woe betide anything that tries to clamp down on those orbiting arms.