That Unfocused She: Freud, Bernays and the Power of Purchase

by Olivia Yallop | June 13, 2013

by Olivia Yallop

I buy, therefore I am. Modern marketing techniques and their effect on everyday consumer choices – to eat, to wear, to watch, even to think – take root in surprisingly radical theories of political thought control. Mass psychology theory, first developed in response to world crisis over a century ago, forms a central role in informing modern marketing industries today.

Edward Bernays, the ‘father of public relations’ and nephew of Sigmund Freud, was the first to harness the power of psychology for commercial purposes. Bernays realized the potential of his uncle’s psychoanalytic techniques for manipulating the human subconscious into believing a certain message or buying a certain product. His new breed of psychological publicity grew alongside American political propaganda. Working for President Wilson on the WWI campaign, Bernays formed practical theories of mass psychology, proposing a radical model of ‘engineered consent’, or the ‘conscious and intelligent manipulation’ of the minds of the American public.

His campaigns were extraordinarily successful. In 1929, Bernays used Freud’s subconscious psychoanalytical methods for Lucky Strike, keen at the time to break into the then socially unacceptable female smokers market. Declaring cigarettes phallic symbols of patriarchal power and women smokers ‘freedom fighters’, he launched the Lucky Strike ‘Torches of Freedom’ campaign. This involved wealthy debutantes lining Fifth Avenue at the New York Easter Parade, persuading millions of women – on live TV – that smoking was empowering and glamorous. Bernays also convinced women that the brand’s colour, forest green, was fashionable. Establishing a “colour fashion bureau”, he hosted a Green Ball at the Waldorf-Astoria and wrote to female-oriented companies as diverse as Cartier, the Ballet Russes and Macy’s, pushing green as the colour of 1934. Green featured on the covers of L’Officiel and Harpers Bazaar. Sales of Lucky Strike cigarettes soared in the first example of mixed-media PR ‘tie in’. With Bernays’s success came huge influence: Pat Jackson, a colleague of Bernays at the time recalls the frequent soirees at his hotel suite looking over Central Park, attended by captains of industry and political figureheads. Bernays had become a sensation, “a magician”.

Bernays’ influence still drives today’s advertising industry. The ‘appeal to fear’ which underpinned wartime propaganda appears in sources as diverse as NHS health warning posters and Lynx ‘premature perspiration’ adverts that play on male anxiety of sexual inadequacy. His ‘third party technique’ lures millions of consumers a year with the pseudo-scientific endorsement of beauty products claiming to be ‘clinically proven’. The use of authority – the ‘direct order’ – appears everywhere from Obama’s instruction ‘Believe’ to Nike’s ‘Just Do It’. The repetitive nature of television adverts, from car insurers to cruise liners, employs ‘argumentum ad nauseam’, originally used to convince the American public that victory in WWI was imminent.

Bernays’s Freudian methods are most startling in his success at marketing the iconic ‘all-American’ home baking range Betty Crocker. Cake from a box was not a popular idea, so Bernays suggested the recipe include an egg to tap women’s supposed subconscious desire to donate their eggs to their husbands. Although bizarre, the idea of ‘creative contribution’ was extremely successful; today Betty Crocker is the highest retailing cake product manufacturer in the world.

Bernays shaped a 20th century consumer focused on the self. Previously, publicity campaigns had extolled the various virtues of the product they were selling without direct relation or appeal to the consumer as an individual. In projects such as his Ivory Soap campaign, Bernays focused instead on the needs and the opinions of the consumer, launching widespread marketing polls in hospitals and schools – a revolutionary concept in 1923. Each commercial product exploited the subconscious motivators of the individual- self-esteem, sexual desire, and subliminal phobias – for higher sales. The result, advertisement’s focus on self-image and individual wants and impulses, is more and more evident in the solipsism of modern consumerism: from Sainsbury’s ‘Be Good To Yourself’ to L’Oreal’s ‘because you’re worth it’ tagline.

The ethics of publicity and psychological manipulation are compellingly complex and frequently unclear, and many question its morality. John Stauber founded the Centre for Media and Democracy, a pioneer organization dedicated to monitoring and exposing PR propaganda. The American writer and political activist also edits PRWatch, an investigative journal exposing ‘spin’ in everything from wholefood companies to Obama’s statements on social security. Stauber insists that the public are largely unaware of the extent to which psychological methods are used for commercial and political manipulation ‘It is important to the smooth functioning of the status quo, as Bernays pointed out, that people be unaware of propaganda. Thus the propagandists have rather free reign.’ The discerning consumer is a rare breed: ‘we are all well conditioned to follow authority and trust experts, and not to think critically or be in charge of our own lives. That indeed is our downfall.’

Stauber is not alone in working to expose ‘spin’. Hundreds of independent watchdogs, committed organizations, and activist authors work diligently to raise public awareness of the ‘characteristic deception and manipulation’ of Bernays’s techniques. In their book Thinker, Faker, Spinner, Spy, William Dinan and David Miller attack the PR industry for their tenebrous morality: ‘corporate social responsibility (CSR) and other ‘ethical’ activities are all subordinated to corporate strategy.’ Stauber agrees: ‘Ethical and moral responsibility exist among the powerful primarily to the degree they fear the public and exposure. There is no real sense of it in their daily operations.’

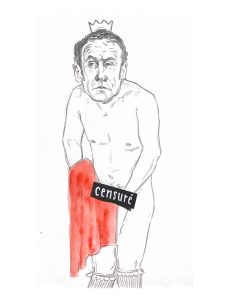

Miller and Dinan believe Bernays’s methods of persuasion surmounted democratic concerns. The politically dangerous implications of his writings have often been criticized, notably certain aspects of Crystallizing Public Opinion: ‘mould the minds of the masses… so that they will throw their newly gained strength in the desired direction.’ Bernays had no despotic aspirations, as dystopian as his ideas of an ‘intelligent few’ responsible for manipulating the masses through the media may appear. According to his daughter Anne, he believed democracy was a ‘wonderful concept’.

However, the American coup d’etat in Guatemala in 1954 displayed the extent to which his techniques were capable of controlling the masses. Alongside the CIA, American fruit suppliers United Fruit Company were in the process of deposing democratically-elected president General Guzman for threatening their agricultural monopoly in the banana republic. Bernays swung public opinion in America towards the cause – hailing the banana as a remedy for indigestion and a patriotic way of supporting an American multinational corporation – whilst casting Guzman as a Communist who threatened the American way of life. The perceived ‘danger’ was used to justify the eventual military overthrow of the Guatemalan government. In situations where politics and publicity are inextricably interwoven, Bernays’s link between democracy and propaganda is less than clear-cut.

The world of media has changed since Bernays dropped propaganda pamphlets by plane into the Guatemalan countryside. A constantly evolving myriad of modern social media platforms is changing the nature of publicity, both for its creators and its critics. The internet facilitates a greater awareness and interrogation of PR practices, such as the organization Spinwatch, who ask for anonymous whistleblowing of ‘inside knowledge about wrongdoing in a PR or lobbying agency’ on their website, with an online form promising to ‘investigate and help get your story out.’ Consumers are also more wary of the tricks of imagery in a digital age, with errors regularly exposed, such as L’Oreal’s series of shampoo commercials featuring Cheryl Cole in 2009, later exposed to have featured hair-extensions. However, John Stauber believes that Bernays’s theories still continue to seduce the general public: ‘Bernays’s strategies and tactics for managing the masses invisibly have prevailed and still predominate the tricks of the propaganda trade. They have merely been adapted and modified as technology and social changes have required.’

The future for advertising is unclear. Yet Bernays’s techniques are still predominant in cutting edge publicity strategies; such as ‘native advertising’, billed as the future of PR, integrating adverts into social media streams until they become quasi-Freudian in terms of subversive influence. ‘Today’, he said, ‘the privilege of attempting to sway public opinion is everyone’s. ‘His methods – whether celebrated or condemned for their political, psychological or ethical implications – have undeniably moulded modern methods of publicity and equipped future generations with the ability to shape consumer choices: ‘Propaganda will never die out. Intelligent men must realize that propaganda is [a] modern instrument… by which they can fight for productive ends and help to bring order out of chaos.’