Men who sold the world

Victor Lustig was a man of large numbers. He spoke five languages, had over 22 aliases and racked up more than 40 arrests in his lifetime. He is also the man who sold the Eiffel Tower. Twice.

He closed the deal posing as a government official. He told the city’s biggest scrap metal dealers that the upkeep of the tower was proving too much and that it would be torn down. He then fleeced one of them for the cost of the metal and a sizable bribe on the side. His contact was too humiliated to tell the police.

The second victim of the scam was less red-faced about it and Lustig had to escape to America. He was imprisoned on a counterfeiting charge eleven years later and died in Alcatraz. But now, years after this infamous landmark salesman was laid to rest, ‘Sold’ signs have been slammed into the ground before the Houses of Parliament, and under the wing of the Angel of the North. The small print specifies that they have been bought by ‘greedy investors’.

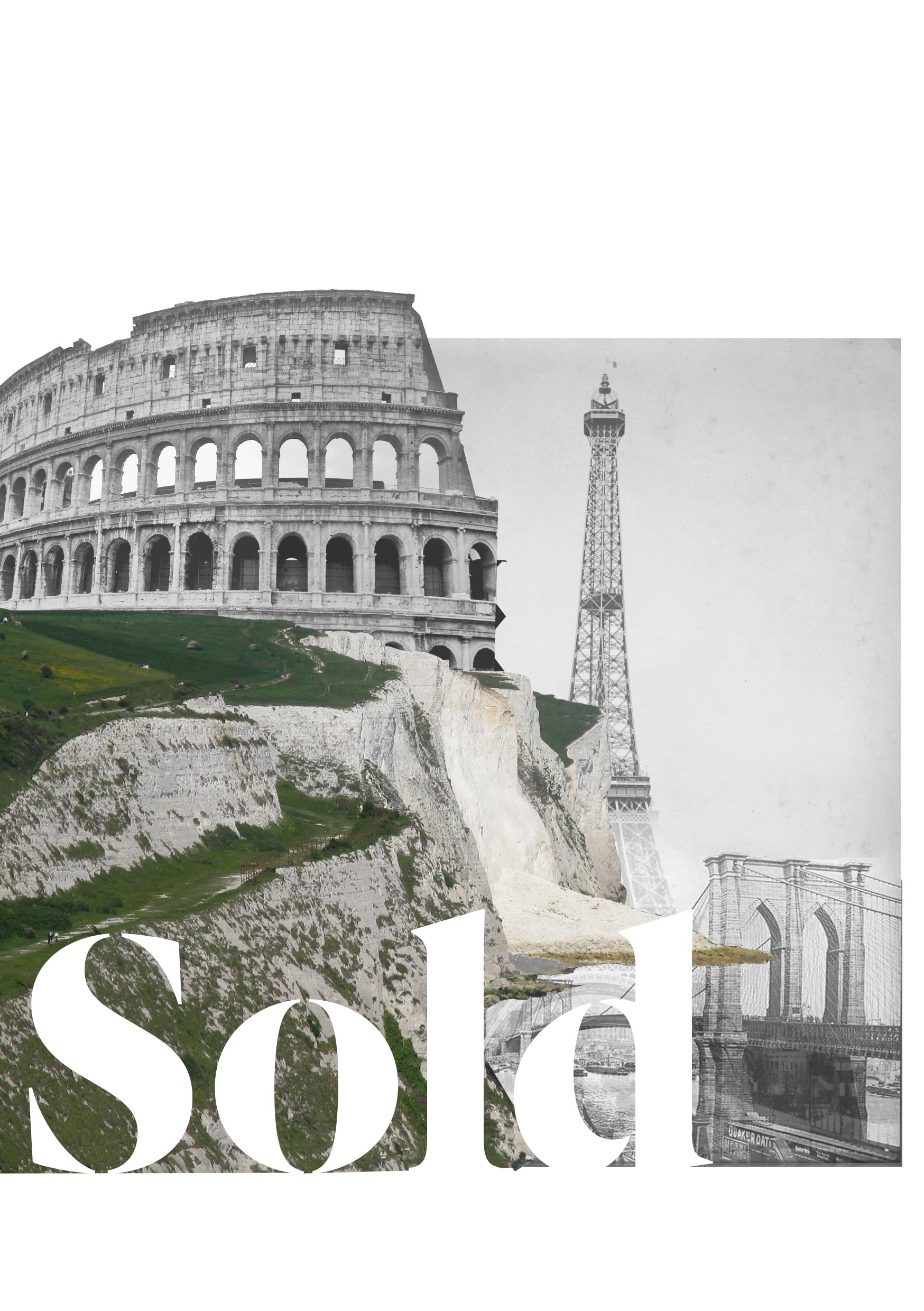

Oxfam’s campaign against land grabs – which broadcasts pictures of the White Cliffs of Dover with a red ‘Sold’ stamp, and has inspired people in Rome to don hi-vis jackets, builders’ helmets and placards that shout ‘Svenduto!’ in front of the Coliseum – is fighting for more large numbers.

In the past decade an area of land eight times the size of the UK has been sold off globally as land sales rapidly accelerate. There are a billion hungry people in the world and this landmass could feed all of them. Oxfam claims that in poor countries, foreign investors have been buying an area of land the size of London every six days.

Alfred Brownell of Green Advocates, an association of environmental lawyers in Liberia sees the fatal problem with this: “You don’t need guns to kill people. When you take food from a village by destroying farm lands and cash crops, you are starving its people.” More than 30% of the land in Liberia has been handed out in large-scale concessions in the past five years, often with disastrous results for local people. Activists like ‘Sam & John’, dressed as ‘investors’ in false moustaches and bowler hats, have been erecting ‘Sold’ signs around their local area and posing for photos brandishing the signs at kayakers to warn them away from trespassing on the ‘Sold’ banks of the Thames.

A two minute film of the day they spent grabbing land last December was produced to be presented to Justine Greening, Putney MP and Secretary of State for International Development. A whistling soundtrack plays alongside the pair as they stomp around in ill-fitting suits, blocking off gardens, roads and grassland. Some people look amused. Others less so – one woman says incredulously to the camera, ‘They can’t just come in and chuck us off our own high street!”

That is exactly the reaction they are after. The film channels the spirit of comedians like Laurel and Hardy, using the humour implicit in the campaign to just declare land ‘Sold’, as a way of reminding people that harmful investments would not be tolerated in their towns. But people in poorer countries are left to fight their own battles; Oxfam reports say that in Honduras, the toll of people killed in a land conflict in the Bajo Aguán region has risen to over 60, and shows no sign of stopping.

Pictures of a ‘Sold’ sign jutting into the sky next to the CN tower appear as ridiculous as the stories of Lustig conning people with money-making miracle boxes, or his swindling Al Capone out of a thousand dollars. These images nod to the humour in the history of audacious con men; George C. Parker is the man who sold the Brooklyn Bridge twice a week for years, setting up a tollbooth and then slowly pushing tourists into buying the whole structure. The Scottish actor Arthur Ferguson played a swindled American tourist in a 1920 play, and when the play closed decided to test a scam for himself. He confided to his marks that the Prime Minister was quietly selling off landmarks to raise cash, and so managed to flog Big Ben and Nelson’s column several times over. Ferguson skipped the country and set up shop in the US where he rented the White House out for $10,000 a year to wealthy English visitors.

But if these stories are comically ridiculous, Oxfam’s campaign asks why we find it more surprising that investors claim land that is home to nice architecture than that which houses thousands of African families who are forced from their homes.

Oxfam says that responsible investment is a large part of fighting poverty, but that these acquisitions are ‘land grabs’ because they may violate human rights, flout the principle of free, prior and informed consent, eschew democratic planning or assessment of the impact or avoid transparent contracts. The investors – or modern day swindlers – are governments, food exporters to rich countries, Wall Street speculators, looting land from Indonesia to Sudan.

The land sold in these tales of con artists was imaginary. It was sold over again, without ever actually being bought. The same is not true in Cambodia, where NGOs estimate that an area equivalent to between 56 and 63% of all arable land in the country has been handed out to private companies. Land the size of a football pitch is taken from workers in poor countries every second.

The sign planted by the Sydney Opera House explains the land is sold ‘at a big cost to poor people’. These stories around con artists and investors are no strangers to large numbers, but this cost is unimaginably high.