Inconspicuous Consumption: the problem with e-books

In 1450 Johannes Gutenberg, a goldsmith and blacksmith by trade, invented the printing press. One of the most significant inventions in human history, it gave rise to a proliferation of printing in Europe and gave birth to modern literary culture.

In 1971 Michael Hart at the University of Illinois envisioned himself picking up Johannes’ baton. He wanted to give back to the world, and chose to do so by making some of the greatest and most consulted texts of all time available digitally, for free. He called this programme Project Gutenburg after his German inspiration, and in doing so he took the first step into the now fully developed and thriving world of e-books.

Both men performed similar actions in radically different ages. One of the most significant similarities between Gutenburg and Hart is the democratising, nature of their creations, intended or otherwise. Hart’s mission is to make available to anyone with an internet connection any text in the world which has run out of copyright. The chances are that Gutenburg’s motives were less noble, and revolved around turning a quick buck, or ‘marck’, as it were.

For a number of centuries following Gutenburg’s invention there was a stigma about print and publishing. It was perceived as ‘low’ and common and not worthy of great art. Many of the same attitudes are now expressed about e-books. American novelist Thomas Pynchon, for example, has been recalcitrant about allowing his books to be converted into e-book format. Such an attitude has the same political consequences of professing a preference for manuscript over print: it favours the expensive and privileged form on the grounds of aesthetics not content.

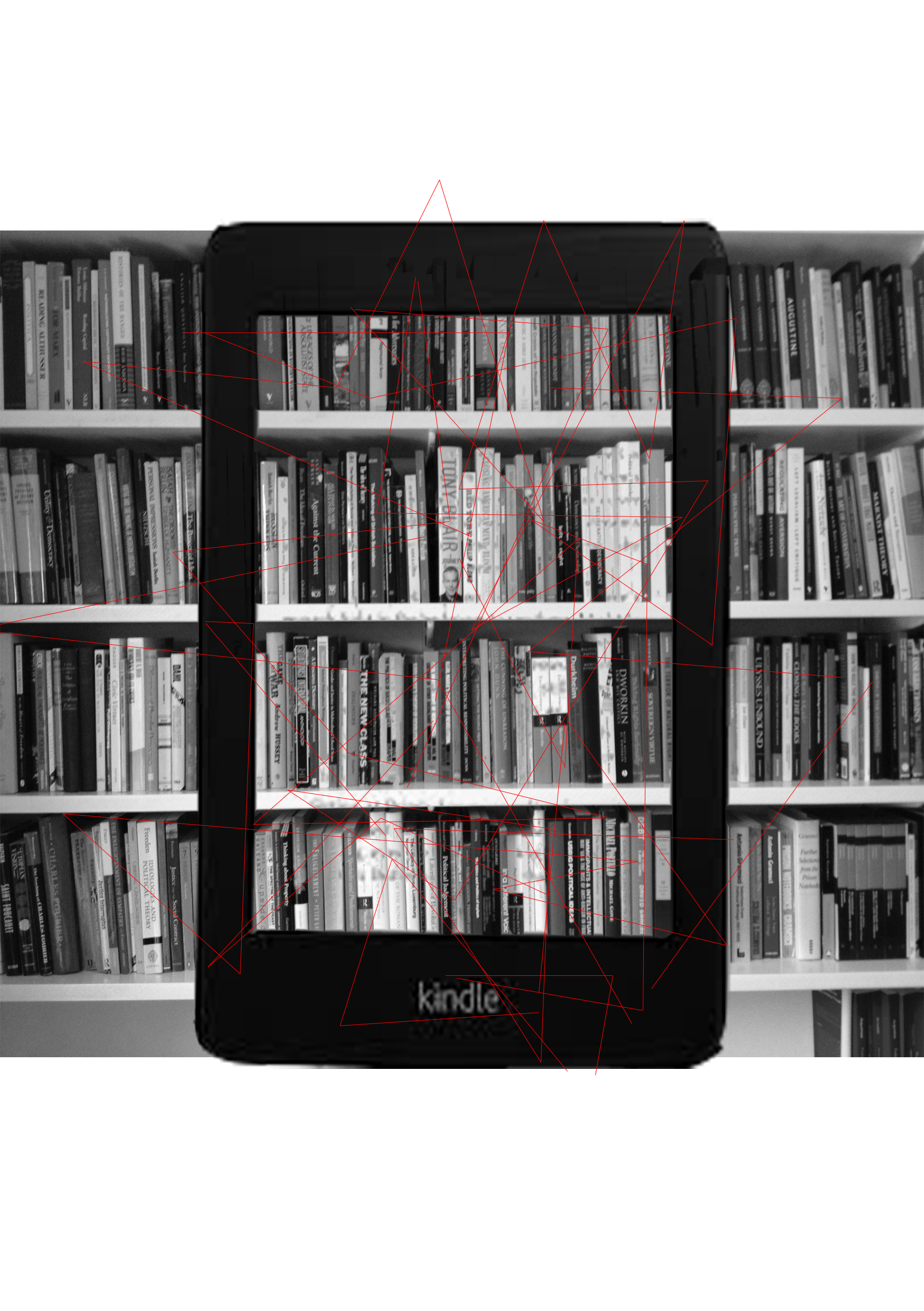

The rejection of the e-reader and the fetishisation of the ‘book proper’ as an objet d’art creates a culture whereby what is being esteemed is not the art that a book contains but the object itself. The Kindle is a relatively cheap method of reading. For £69 (at the time of writing) one can acquire a Kindle that gives them access to books in the kindle store, vast swathes of which, due to the efforts of Hart and his followers, are now free. Virtually any classic text is available to obtain, delivered instantly, stored indefinitely and taking up little storage space. Even the ones that cost aren’t expensive. Only one of the top ten ‘paid’ books on Amazon, costs more than two pounds and the majority are selling for 20p each. The book is more expensive in the long run. Once you’ve read ten books you’ve all but bought the Kindle. So why the objection?

It comes down to aesthetics and identity. There is undoubtedly a performative aspect of reading. There are certain books that it is a statement to read, and we are all victims of this—who is not more impressed sit next to someone reading Tolstoy than the newest Jodi Picoult novel? An e-reader enforce anonymity: you now have to stand up and tell the whole tube carriage how moved you are by the plight of the 19th century Russian women. This objection is itself, a form of privilege—it is intellectual snobbery and reeks of the classic reader who reads something only to have read it.

This is the problem with the e-reader. People read books on them that they actually enjoy—they have increased the market for popular fiction and there is now a Darwinian capitalist model in operation that what sells lives. Publishing houses are destroying themselves in order to remain afloat, the aforementioned 20p e-books driving them into the ground.

Within the publishing industry there is uncertainty as to what e-readers will mean in the long run. If the publishing world is as stagnant in the face of technology as record labels have been they might face a similar fate. The reading public seems to have gained the only victory, given wider access to more texts on a more democratic basis. It remains to be seen if it will get over its snobbish reluctance to celebrate it.