Sex, irony and advertising

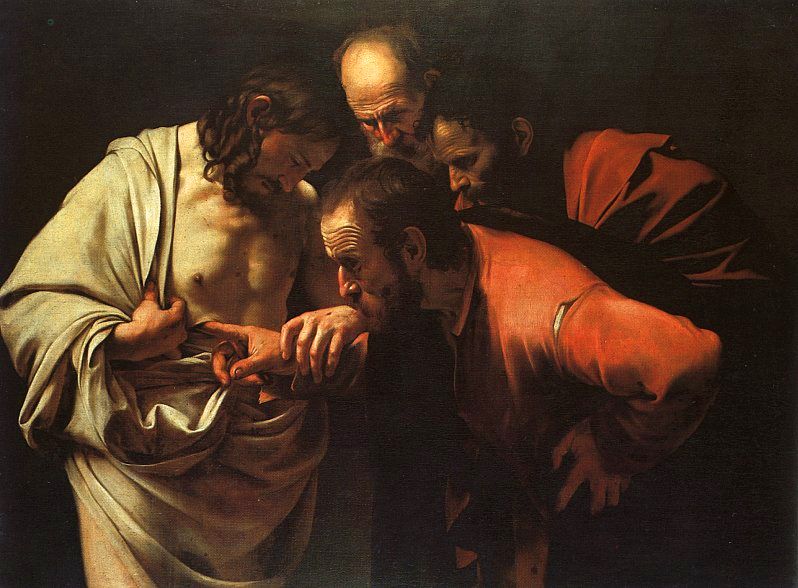

The actress in the first advertisement ever presented on British television was a crop-cut young woman named Meg Smith. In the advert for Gibbs SR toothpaste, which dates to 21 September 1955, Smith is shown from the neck up, brushing her teeth with boundless enthusiasm. Bookended by shots of a snowy wood and a pseudoscientific explanation of the product’s chief active ingredient, Smith’s six seconds in the spotlight bring a watered-down sensual appeal to the clip, completing the classic troika of nature, sex, and science that have come to define modern advertising.

But in the past decade ad agencies have engaged in a self-conscious inversion of familiar ‘sex sells’ tropes directed at those of us born roughly after 1985; those of us who do not buy things but instead “buy things.” By selling sex ironically, advertisers can mock themselves and ease the viewer into a winking acknowledgment of a commercial’s artifice—all while exploiting the sexual imagery that got them there in the first place.

Who could forget Paris Hilton’s spot for Carl’s Jr. in 2005, which depicted the scantily-clad celebutante washing a Bentley before cramming an enormous hamburger in her mouth? Domain name vendor Go Daddy has been peddling ads of the same ilk during the U.S. Superbowl for years now, most recently featuring supermodel Bar Rafaeli making out with famous-for-being-goofy-looking background actor Jesse Heiman. Even Coca-Cola, who typically play sincerity close to the vest, have recently ventured into ironic sex appeal territory themselves.

In fact, the schlubby-guy-meets-supermodel has become a trope unto itself, advanced in large part by Judd Apatow films and the Axe spots depicting women variously attacking and molesting its average-Joe customers.

Conventional advertising taps into an audience’s subconscious by placing a beautiful man or woman in the general vicinity of—or better yet, using—a particular product. But now the sex is front and center, as if to level with the audience. The game has changed, they seem to say—we don’t take ourselves seriously either! What better way to fight phoniness than with self-aware phoniness? And if you happen to enjoy the eye-candy along the way, well, who could blame you? Not that we should confuse this irony with real sincerity; the truth still doesn’t make money. Consider Death Cigarettes, a UK brand from the early nineties that didn’t even last the decade. Or Hyundai, who recently pulled a morbid clip displaying a man’s frustrated suicide attempt as a result of his car’s clean emissions. Nobody wants a hard dose of reality in between episodes of Geordie Shore.

But sex still sells, especially when it’s gussied up in postmodern polish. And no matter whether you’re enjoying the ads or “enjoying the ads”, buying stuff or “buying stuff”, your money is theirs all the same.