Left Foot Forward

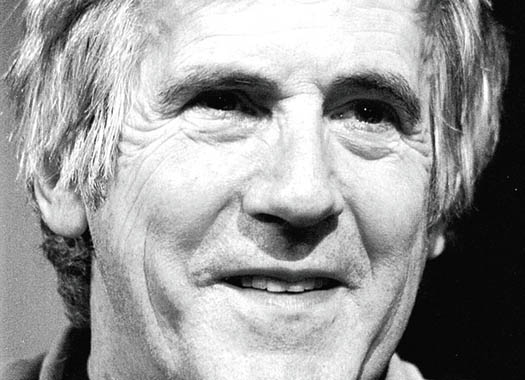

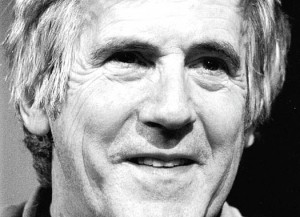

The late campaigning journalist Paul Foot was renowned for his outspoken views on the British Establishment. Palash Davé spoke to him in 1994 about his career.

The late campaigning journalist Paul Foot was renowned for his outspoken views on the British Establishment. Palash Davé spoke to him in 1994 about his career.

They forgot to mention the fifth Beatle. In all the hype about the retro Anthology LP, one man whose pudding-bowl haircut and revolutionary politics have stubbornly prevailed since the sixties went scandalously uncelebrated. Paul Foot’s pen has, for some thirty-five years, been the scourge of bent quangos, greedy bosses, unjust justices and assorted grand and petty tyrants. He remains, at fifty-eight, the eternally petulant enfant terrible of British radical journalism. Former editor of Socialist Worker, erstwhile investigator-in-residence at the Daily Mirror, regular columnist on Private Eye and the Guardian, Foot sits in his Soho office and laments the state of the Nineties press.

“It’s in every sense dreadful… compared particularly with when I started at the Eye in the late sixties and went to work at Socialist Worker in the seventies… The standards were so much higher… The Sunday Times is a classic case, a paper which people were actually excited to read. Safe, as far as the rulers were concerned, but… all the time snapping at their heels. It was a great newspaper compared to the sort of tame PR job they produce their now…” Immediately, the materialist analysis of Foot’s Marxist world-view comes into play.

“It’s the fault of the time we live in and the proprietors who are sustaining them… The actual ability of journalists in the field is at least as high as ever… It comes back to the state of the battle between the people who have property and the people who haven’t… The people who’ve been stashing up these unimaginable riches on the backs of the poor and the workers… have been having it all their own way for about sixteen years now without stop. And the newspapers reflect that… The buying of things and the hierarchical control that underpins the exploitation that runs in society, is incomparably worse than it was thirty years ago… Everything is bought, especially in journalism.”

When Robert Maxwell bought the Mirror in the early eighties, he inherited Paul Foot’s weekly campaigning column. Foot insisted on maintaining full editorial control within his column, a condition which Maxwell accepted and only once tried to flout. It was an uneasy professional peace, peppered with accusations from purist lefties that Foot was selling out by working for such an arrant tyrant. He insists that “everybody works for capitalists in one sense or another… and I always remained a strong trade unionist on the side of the workers against the employer… The Mirror was read by working-class people almost all of whom I had a regard for… There was no journalistic compromise… So the business of ‘working for Maxwell’ never really worried me very much.” The crunch came with the arrival of David Montgomery, appointed chief executive by the banks who took over the Mirror after the collapse of the Maxwell Empire.

“Montgomery came in with the specific intention of smashing the unions… He sacked all the casual workers… and almost any journalist who represented any challenge or spirit of independence in the place… I stayed there as long as there was a breath of a fight against him, but in the end it was obvious that I would have to try and overcome that contradiction.” He penned a hatchet job on the Mirror Group management. “It was the only column that was ever pulled – in a way beautifully exposing the whole hypocrisy of the free press, that you can criticise anything except the people who are making profit out of the thing that you’re using to criticise. Ha!”

According to the Australian journalist and film-maker John Pilger, one of the key tasks of the radical journalist is to recognise as spurious the widespread notions of journalistic ‘objectivity’ accepted by liberals and propagated by reactionaries. One such is Tory MP Roger Gale, a former journalist who criticises Foot for “deciding what his stories will say before he does his investigation. Journalists should be objective.”

“I think,” counters Foot, “objectivity is a mirage in this sense – that everybody has ideas. If they don’t have ideas, they’re bloody awful journalists… It drives you away from objectivity to decide even how you’re going to write your first sentence about a story – what’s interesting here, what isn’t interesting? What stands out, what doesn’t? … It’s written in the history of journalism that those journalists who had no opinions, who didn’t care tuppence about any kind of social consequence or relevance of what they were reporting, were often the worst, most bland reporters… Where it’s not a mirage is to pretend that facts don’t exist… What you might call the ideologues, they say, ‘Well there are no such things as facts, there’s the class struggle and you take up one side against another’ – and that can be said on either side of the class division.”

Paul’s relationship with his uncle Michael – literary scholar, former Labour leader and erstwhile Beaverbrook newspaper editor – has long been one of respect tempered by passionate disagreement “over anything that happened after 1880!” Although the period when Michael Foot was in government was “difficult” for relations with his revolutionary nephew, Paul remarks that “I seem to disagree with him more and more, [notably over the Gulf, Bosnia and Blair] and at the same time to love him more and more.” This good-humoured separation of the personal from the political is not something Paul extends to the turncoat villains of the Labour right, nor to the bloated capitalist fiends who tyranny he’s dedicated to exposing. Steve Platt, editor of the New Statesman, praises Foot as a consummate “polemicist” nevertheless lacking the intellectual rigour of a Hobsbawm or an E.P. Thompson. There’s perhaps a degree of crudity in his ad hominem moral attacks on those who run the system (as opposed to just the system itself) which may be the price one pays for attracting a large audience. Comparing Paul’s sharp, highly entertaining political-literary tract Red Shelley with Michael’s equally passionate but denser Byron: The Politics of Paradise, one constantly sees Paul eschewing the subtle qualification in favour of the sweeping witticism. Paul swings effortlessly between learned and demotic journalism, and is acutely aware of the tensions between populism and intellectual and political purism.

“I used to go down to [Mirror editor] Mike Molloy’s office and say, ‘Look this is disgusting, you’ve got a spread here on Seventeen Things You Might Like To Know About The Queen… “The queen likes dogs!” Everyone knows that, it’s a waste of space.’ He just listened to me and said, ‘All right, thanks very much Paul, always glad to hear your views,’ and sent me off…” Molloy commissioned a poll to assess reader response to two articles. “The figures have stuck in my memory. 96 per cent singled out the piece about the Queen… Something like 82 per cent had actually read the whole spread about corgis and so on… For my column I think twenty eight per cent had even started and much less had finished. After that I was inclined to shut up a bit. I mean tits and things I would complain about, but it’s a very hard thing to pontificate about what should or shouldn’t be permissible in popular newspapers when you run up against that sort of figure.”

“Shelley led me down so many different paths… It was really the reading of Shelley which opened my eyes to the radical tradition in English literature, English history.” Foot begins his book Red Shelley with the gripe, “I share with Shelley a rotten education at University College, Oxford.” The biographical parallels don’t end there. Emerging from privileged political-elite families close to the land, (although Paul describes his family as being “two generations away from the rising bourgeoisie”) they are both quintessentially class-treacherous renegades. Foot’s own politics sprang initially from a liberal humanist, rather than an explicitly class background. At Oxford he edited Isis and founded, with fellow old-Salopian Richard Ingrams, the scurrilous scandal-sheet, Parson’s Pleasure. Emerging from his undergraduate presidency of the Liberal Club and the Oxford Union, his socialist awakening galloped apace with his first journalistic posting to the Glasgow shipyards. Like the early Marx, who “started out merely as an extreme democrat and later discovered that the hierarchical control of property is what keeps people down,” Foot “doesn’t come from a shop floor experience of exploitation.” But he insists that this doesn’t make his views any the weaker, and his staying power as a devoted activist of the Socialist Workers’ Party, compared to such proletarian former comrades as Gus MacDonald of the Gorbals, “once a rampant Trot, now a millionaire chairman of Scottish TV,” is something of a feat.

The continuing faith in revolutionary change of a man who has fought Stalinism as virulently as capitalism has the intensity, though not the irrationalism, of religious fervour. “It seems to me so bloody obvious that if you’ve got a system which is founded on a tiny section of the population growing rich at the expense of the rest… and taking all the decisions about society so that they should grow richer and more powerful – which without denial sums up the world today… There’s absolutely no alternative but to devote your life to ameliorating, preferably ending, that state of affairs.”

Times change, and politics change with them. We looked back to the archives to bring you this gem from 15 October 1892; the product, we think, of a slightly different editorial line.