Sounds of freedom and songs of change

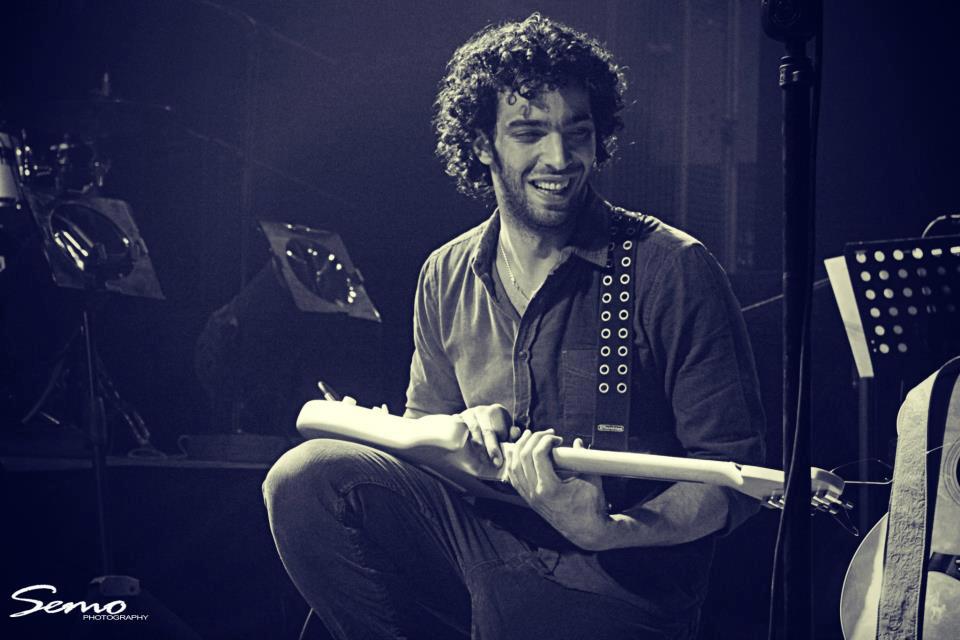

It is the 31st of January 2011. Egypt begins its sixth day of widespread and escalating protests against the corruption of Hosni Mubarak and his government. Cairo draws the largest and most tenacious numbers, undaunted by the recent internet and mobile blackout, increasing military violence, and new curfew. Some 250,000 demonstrators swell in and out of Cairo’s largest public space, Tahrir Square, over the course of the day: talking, chanting, blogging, setting up tents and manning food stalls. Amongst them is an engineering student in his twenties, clutching an acoustic guitar. At present, he is just another face weaving through the crowds, aside from his unusual height and pony-tail, but in less than a fortnight, Ramy Essam will have become an internationally-recognised revolutionary songster.

Music pervaded this uprising at global, national and local levels, with a staggering breadth of contributions. Solidarity from abroad arrived in the form of professional hip-hop and pop singles, an abundance of home-spun internet tracks, and even a resurrection of the Bangles’ ‘Walk Like an Egyptian’, in possibly the first constructive moment of its existence. The Egyptian music scene itself experienced a dramatic shake-up, as artists normally suppressed by heavy censorship were openly engaging in political debate. “Before, we’d only used metaphors to talk about the corrupt system,” says Karim Adel Eissa of the Cairene hip-hop band Arabian Knightz, “but once people were out on the streets, we were just like, ‘Screw it.’ If we’re going down, we’re going down.”

Tahrir Square alone hosted a thriving soundscape, with its permanent backdrop of rapping, singing, jamming and blasting speakers. Makeshift stages and sound equipment were eventually assembled to accommodate the ubiquitous music, and performances ran into the early hours, providing motivation to those staying through the night. Essam was thrust into the limelight the night after his arrival, singing Irhal (‘Leave’) derived from slogans flying around the square. “I tried to see what the people around me needed,” he recalls, “…it’s the first time I sang in front of this many people… almost everybody in the square welcomed me.” His performance was an instant crowd-pleaser, and footage of it rapidly went viral on YouTube. Essam remained in the square protesting and performing; “every time a new development happened, I would hide out in a corner to compose.”

Youth were not the sole protagonists fronting Tahrir’s music scene. El Tanbura, a group of seasoned folk instrumentalists and vocalists, brought the sound of vernacular urban song to the throng. Their founder, Zakaria Ibrahim, explained; “we revive traditional music to remind people of their history. Traditional songs and revolutionary songs have a common desire for freedom.” Older works were also recast to serve a new political climate, an example being classical singer Sayeed Darwish’s 1919 setting of Bilady, Bilady, Bilady (My country, my country, my country), rejuvenated by rapper Mohammed al-Deeb.

“We revive traditional music to remind people of their history. Traditional songs and revolutionary songs have a common desire for freedom.”

Amidst the turmoil, what is it about music that engages protesters? As a hybrid of music and poetry, song can coherently express political sentiment in a form comprehensible to educated and illiterate listeners alike, which arouses emotional and physical responses through musical affect. Music’s capacity to incite is widely discussed by psychologists and sociologists as well as being explicitly recognised on the ground. “It makes a difference,” states Henry Habashi, a 21-year-old tabla player, “when we start playing music. Before you know it, everyone’s dancing and cheering. It brings people together and reminds them that they are not alone.”

The music of the Egyptian revolution was on the front line, relevant and powerful, but also hazardous. Essam was singled out by the authorities for prolonged torture as a result of his performances. He has since returned to the square, along with many other musicians, as the country’s political struggle continues. “We can sacrifice anything we have,” he said in November, “even our souls, to make Egypt a free country.”