Sexist politics, silencing, and predatory tutors: Oxford feminists’ battle to be heard

by Libby Cherry | July 15, 2018

Throughout her life, Judith Okely has experienced institutional misogyny first-hand. When she was at secondary school, she was told by her headmistress that it would be inappropriate for her to apply to Oxford. Not because of academic inferiority—but because she was pretty and, therefore, marriageable. Going to university, she was told, would be “selfish”.

Okely ignored her. She went to Oxford—where she became the first female member of the Oxford Union—and now she is an eminent feminist anthropologist. But her headmistress was not the last person with whom Okely had to contend.

Nowadays, taking a “feminist approach” is hardly controversial. It has become part of our academic tool-kit, a failsafe framework for students to deploy in essays across all the humanities and social sciences. But we can all too easily overlook just how recently academia has accepted feminism as part of its core. It was only this year that Oxford announced the new undergraduate paper in feminist philosophy, despite many of its texts being written decades ago.

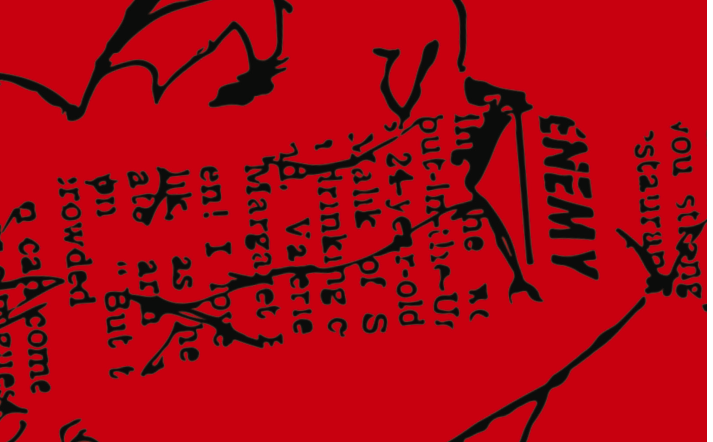

Feminist academics such as Okely, let alone those writing on women, have long been victims of systematic structural silencing. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Oxford. Here, institutional tradition has at best sanitised and at worst denied the work of feminist academics. Translated into the banality of a reading list or module syllabus, feminist writings have been dissociated from the ongoing struggle of their authors. I spoke to just some established feminist scholars about how different Oxford and society were when they started out as academics—and how they overcame these challenges.

I put the first question to Okely. According to her, our nostalgic view of a liberated Sixties is a fallacy. Far from espousing free-spirited hedonism, the world she describes is almost stereotypically Victorian. Her memories of her college St Hilda’s, still all-female at the time, make it seem convent-like: girls who got caught with their boyfriends were told they were “unfit for education”, and abortion clinic phone numbers were swapped under the table at Hall (contraception was prohibited for unmarried women).

Having studied for a year at the Sorbonne, Okely came to university with a worldview in stark contrast to those of her chastened peers. While on the continent, she had become fluent in French, picked up a taste for black leather jackets, and had pinned torn-out pages of de Beauvoir to her wall. But in Oxford, Okely says, “there was no question of feminism.”

Before even arriving at Oxford, Okely vowed to get women into the Union as a point of principle. And two votes later, she was successful in her campaign, having rallied supporters from across the political spectrum. But if this looks like a rupture of patriarchal structures, the criticism of the change only underlined the degree to which sexism was entrenched—not just in university circles, but in the wider public.

“I had a lot of publicity in the media,” she said. “As an undergraduate with long hair who wore makeup and black leather jackets, the media would follow me all over. One person on the [Union] committee sanctioned my membership because he said I had only got there because of my looks.”

Okely’s tone remained dryly ironic throughout our conversation, but I couldn’t ignore the dark truth of what she was saying. She took up a lot of roles at university—a student, a Marxist, an activist—but in al- most every area she was met with resistance because of her gender.

When speaking about her experiences, Okely continually referenced the “virgin/whore” complex. While to me it seemed outdated, it applied disturbingly well to the contradictory role that women at Oxford felt compelled to emulate. A web of public structures monitoring the girls’ chastity with almost puritanical zeal existed alongside an equally institutionalised network of sexual harassment from male students and tutors.

For female doctorate students, receiving sexual advances from supervisors was, Okely said, “a given”. “I always said thank God my PhD supervisor was gay, so I was safe. I mean that’s the scandal. There’s a guy—he’s actually my age—and I know he demanded sexual services from all his female PhD students.”

One of Okely’s female students told her that her supervisor, after having flown out to the country where she was doing fieldwork, demanded that she sleep with him. Such behaviour was not only normalised, but necessary if female students wanted to be successful. According to Okely, only the women who gave in to these propositions, “got the right references and got the right jobs.”

But Okely did not escape being sexualised herself. As a self-proclaimed “radical leftie”, Okely had little chance of being elected to the Oxford University Labour Club, given the party establishment’s centrist politics. To her surprise, however, she found herself appointed. But her pride at the achievement quickly tempered when she discovered the potential reason for her success.

One of Okely’s friends later asked a senior member of the committee why they had allowed such a radical left-winger to be elected. The official—the son of a cabinet minister, who would go on to be a professor at Oxford—replied: “we needed a fuck for the executive.”

Dr Janette Davies, an anthropologist at Oxford’s International Gender Studies Centre (IGS), told me women’s position at Oxford could be considered an extension of the social science concept ‘Muted Group Theory’. “In any society structure the dominant is always male and he can mute anybody’s voice—but mostly the woman’s voice.”

Although the term is more typically used in the context of far-flung rainforest tribes, Davies explained how it mirrors the historic institutional silencing of female scholars. Plagued by requests for sexual favours and discouraged from entering university—let alone academia—women were left unrepresented and unstudied.

Even 20 years after Okely’s student days, Ros Ballaster, currently a professor of English at Mansfield, told me the how in the 1980s curricula remained “archaeologically frozen”. Impatient for change, as a student Ballaster became part of Oxford English Limited, a group of “socialist-feminists” campaigning to modernise the English Faculty reading list.

She helped set up a feminist theory reading group to pour over what would become seminal texts in the feminist arsenal. But while this sisterhood may sound romantic, the practicalities of their situation were difficult. These feminist moonlighters also had lectures to plan, essays to mark, and households to run. There may not have been raging chauvinists shutting down the groups, but the everyday societal biases women faced formed another formidable obstacle to the group’s activities.

The outsider status of groups such as Ballaster’s is characteristic of seemingly all feminist study. The Cross-Cultural Centre for Research on Women (now the Institute for Gender Studies) was set up by women anthropologists in Oxford in 1983. But it remained firmly outside of the university’s responsibility, receiving no funding and little support.

In fact, the Centre’s newsletters from the 1990s unintentionally but constantly underline the parallels between their research on the oppression of women worldwide and their own struggles at Oxford. In a 1994 edition, a report on a workshop in Cairo where anthropologists discussed “perceptions of women’s rightful gender role” sits alongside another article describing the appointment of Professor Marilyn Butler as the Rector of Exeter, the first female head of a formerly all- male college, as a “major breakthrough for academic women”. The researchers’ interest in the plight of their international counterparts came with a deeply personal significance.

Although not at Oxford at the time, Professor Lorna Hutson was instrumental in setting up the Women’s Writing and Gender module at the London universities. It became a runaway success, but her memory of bringing it into existence was so traumatic that Hutson said she had “repressed it, it was so painful.”

Hutson had been included in the committee of academics advocating for gender studies in the ‘90s, despite being relatively junior. However, on arriving at a faculty meeting where the module’s introduction was to be discussed, she found herself the only representative of the group present. She left early, in tears after the rest of the faculty, “tore [her] to shreds about it.”

“I was surprised by what had happened,” Hutson recalled. “I didn’t know that no one was going to turn up to this meeting, I didn’t realise I would have to speak and I didn’t realise I would be told that I didn’t have the rights to be in there. The combination of things, it made me cry. Which is something I’ve never done before or since.”

Setting up Oxford’s master’s degree in Women Studies, Ballaster too felt the full force of bureaucratic inertia when it came to curriculum reform. Not only did the new degree attempt to tackle subjects which had formerly been deemed unworthy of study, but it was attempting to bring together elements tradition- ally kept separate within individual disciplines. As a result, the academics were constantly pitching their ideas from the outside, trying to persuade faculties to lend staff hours to the course. The study of women’s experience seemed, in its very inclusivity, barred from institutional existence and structurally destined for marginalisation.

But when the Women’s Studies degree was finally established in 1996, Ballaster admits her reservations about losing the “strategic separatism” that had previously provided such freedom in research. As Okely said, greater institutionalisation meant losing feminist studies’ occupation of the “non-place… where the usual social structure is not there” and that had allowed discussion to circulate without mediation. “It’s that kind of age-old problem—are you propping up the system or dismantling it from the inside?” Ballaster sighed.

“I think in some ways we were propping up the system. We were saying ‘It won’t cost the University any more, you won’t have to change your library holdings massively.’” Forced to graft, shift and perform to find a platform, these women paradoxically risked sacrificing the anti-establishment fervour that had given their ground-breaking work its impetus.

Okely described a similar situation when applying for her first lectureship at Durham during the 1970s. Instead of being impressed by her feminist backgrounds, the all-male selection panel found her qualifications concerning. She remembers being told: “We see you’re a feminist. But would you still be interested in the job if you couldn’t teach anything about women?” Okely chuckled: “And I said, ‘I promise I won’t talk about women, I’ll only talk about men!”’

To be a female academic in male world, let alone to lecture in subjects relating to women, meant having to effectively re-incarnate male stereotypes. Besides relinquishing feminist politics, one had to promise not to have children, for fear of being considered “unreliable”. Such requirements drove Okely’s predecessor in the Durham post to desperate measures. She told Okely that at her interview, she had broken down into feigned hysterical feminine sobs, declaring (untruthfully): “I’m barren, I’m barren—I can’t have any babies!”. It worked. They gave her the job—without a fertility test.

“If she hadn’t got the job at Durham, she said she would have gone to a laboratory to ask for female ovaries and put them in two bottles,” Okely recounted. “Then, at the next interview, she was going to say, ‘I’ve had my ovaries removed! So that can assure you that I’ll be a good academic!’”

This absurd image of a woman clasping stolen reproductive organs in a glass jar, simply to get a junior academic position, only indicates the lengths of the constraints which Okely’s generation faced. In fact, this kind of grim-faced humour is one that all the academics seemingly turned to. Women’s Studies’ lecturers became famous for wearing badges emblazoned with the words “Oxford’s Cheapest Faculty”.

Feminist theory may sound technical. But it is grounded in material reality, and entwined with the lives of those who have written it and shaped it. When we hear academics today lecture on feminist thought, their oratory power isn’t stemming wholly from their rhetorical prowess. They are speaking with the weight of experience—the weight of suddenly unrepressed silence—behind them.