Too obscene for the screen

by Inès Bonneau | April 15, 2018

Imagine being a small restaurant owner in Newport Beach, California in 1971. It’s an average start to the day like any other, you’re going around making sure that everything is ready for opening time and then, the postman drops off some mail. This is nothing exciting, you might get a couple of bills, a personal letter if you’re lucky. Getting a brochure advertising books such as Sex Orgies Illustrated and An Illustrated History of Pornography was probably not what you expected. To make matters more awkward, it’s your middle-aged mother who opens the brochures. The culprit behind this uncomfortable situation was Marvin Miller, the owner of a mail-order pornographic film and book business. The outraged family took Miller to court, where he was convicted on charges of distributing obscene material.

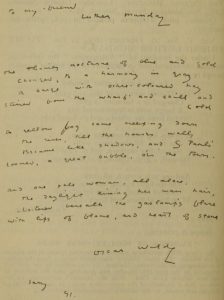

It did not end there for Miller, and this small affair ended up in the hands of the US Supreme Court in 1973. This court case was about more than social morals—it was about freedom of speech. At least that was how Miller defended himself, by arguing that obscenity should be protected by the First Amendment, because it was not devoid of social value. The outcome of this case (Miller v. California) redefined the term ‘obscenity’ such that material could be deemed obscene if it lacked ‘serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value’. But does this provide a objective standard by which to judge pornography? Even in a previous obscenity trial in 1964 (Jacobellis v. Ohio), Justice Potter Stewart recognised that he could not define pornography, but famously said “I know it when I see it…”

Our ideas of obscenity have evolved over time due to the normalisation of sex. Seeing a naked person in an advert is not as shocking now as it would have been back in the 1970s. ‘Obscene’ is too relative a term to carry any real meaning. The Miller verdict led to a sudden boom in the distribution of pornographic films, giving rise to the era known as the ‘Golden Age of Porn’.

Seventies pornography ranged from the amateur to arthouse cinema. The first example of porn being presented as an art form was in Andy Warhol’s Blue Movie (1969), which depicted a couple going about their daily lives, talking about the Vietnam War, and their sex life. There was no plot, no climax, no shock twist at the end, and the dialogue was as mundane as could be. It seemed to be like any other porno at the time, except for the fact that its director was famous, and there was no intent for it to be seen as a porno. It was the first adult film to have been widely released in the US. Like other sexually explicit films at the time, it was taken down from some cinemas, but given that it was released to the public initially, must have been deemed to have ‘artistic value’. Yet besides having been filmed by an artist, it is hard to see how Blue Movie necessarily had any substantive value to it. What, then, does it mean for a pornographic film to have artistic value? In the case of Warhol, it seems that value lies in the intent or concept behind a work of art. In other words, sex has to be intellectualised in order to be seen as valuable, and not merely obscene.

Art became a sort of loophole for porn directors, whereby if they could show technical skill in their filmmaking, their work was less likely to be banned by state courts. The way in which they tried to turn their films into ‘art’ was through the mimicking of Hollywood films: the plots became more complex, more attention was paid to character development and technical skill. Sex scenes had to be moralised insofar as they had to be secondary to the main plot, representing for example the fulfilment of a romantic relationship. This also gave mainstream filmmakers more freedom to include sexually explicit material.

As censorship became more relaxed, a sort of symbiosis occurred where Hollywood was embracing pornography for the sake of artistic license, and the porn industry was embracing established cinematography techniques to avoid censorship. This is not to say that it was the only a way to avoid censorship and increase distribution, but it’s doubtful that most of these porn directors wanted to be part of an ongoing revolution of sexual normalisation. At the end of the day, pornography was about money, not art, so this assimilation into the mainstream was a must to increase profits.

Radley Metzger is one of the most acclaimed film directors from this period. He did not start his career working in porn, yet many of his films are essentially erotic adaptations of classic works of literature: Pygmalion became The Opening of Misty Beethoven (1976), and The Lady of the Camellias became Camille 2000 (1969). Metzger’s style was an eclectic mixture of seventies kitsch and European decadence. When watching his films, it is clear that they imbue sex with meaning, insofar as sex is not only about pleasure—it can also teach us a lot about human relationships.

What Metzger found empowering in porn was that he could tell stories that questioned social conventions. The sexually promiscuous woman didn’t get punished, and sex was not pigeonholed as exclusively physical or emotional; it could be both. In essence, there was no shame: pornography provided relief from sexual stigmas. This genre created an environment where human sexuality could be discussed openly. The acceptance of porn as art by film critics allowed mainstream film directors to use sex as an artistic tool, but also slowly normalised such conversation in American culture. Seeing sexual acts on screen, in commercial cinemas rather than secluded sex shops, allowed the social stigma around sex to slowly decline.

Erotic films aside, the explicit nature of many films in the 1970s gives the impression that many directors were too eager to take advantage of new attitudes of sexual permissiveness, with the cinema industry becoming more exploitative and sexist than it was before. As the decade drew on, sex began to consume the film industry to the point where sex was depicted for a shock factor, and not for art’s sake.

We return, then, to the fundamental question: what makes pornography artistic? Looking at the previous examples, it seems to be a struggle between conceptual vision and technical skill. Then again, obscenity laws aside, we are left with the question: does pornography need to have artistic value? If its sole function is to bring about sexual arousal, then there is no need to intellectualise sex through either skill or concept. However, the use of sex as a cinematographic tool is an important topic, not only in terms of censorship but also in terms of what onscreen representations of sex do for discussions surrounding it.

A modern attempt at depicting meaningful sexual relationships is Love (2015) by Gaspar Noé, the first 3D pornographic film. Noé wanted to make a film about ‘sentimental sexuality’, which is the aim of the main character in the film, Murphy. However as with his other works, the imagery is crowded with saturated and intense images. Like Metzger, he too solely depends on impressive cinematography to make up for the lack of character development.

There is a fine line between a film being ‘sexually explicit’ and it being ‘pornographic’. Pornography, by its very definition, is only about sexual arousal, whereas if a film is described as ‘sexually explicit’, sexual depictions are used to bring out the relationships between the characters. Porn, itself, might not have artistic value insofar as it indulges too much on senses rather than on the mind, but this does not mean that it has no value at all. The works of Metzger and other pioneers of the Porno Chic era are very beautiful, from a visual perspective. Furthermore, the obscenity trials did not only allow porn directors to make more money, it also made people question their attitudes towards sex and how it is talked about in society.

Despite the many problems in the porn industry, such as its treatment of women, the increased discussion of sex has contributed to the start of feminist porn, which acknowledges female sexuality outside of the male gaze. In this way, one can say that pornography has social value, but when it comes to art, then no test can determine its value. It definitely couldn’t be determined by a Supreme Court judge in 1973.

Artwork by: Niamh Calway