Letter to the Isis: #1

by Flo Ward | January 10, 2018

The existence of an academic elite at Oxford can never be justified unless it is open to students of every background – The Isis, October 1978.

This is a statement made in the first article of the 1,684th edition of The Isis, and despite being published nearly forty years ago, it still rings painfully true. Rewind a couple of months to late October, and you’ll remember David Lammy’s accusation of Oxbridge’s ‘social apartheid’ that caused ripples amongst the staff and students of both universities. Lammy’s research revealed ream upon ream of shocking statistic: Oxbridge makes more offers to students from Eton than those on free school meals across the entire country; from 2010 to 2015, a quarter of Cambridge colleges failed to make any offers to black British students; 82 per cent of Oxford offers go to the top two social classes, the children of barristers, doctors and chief executives…I could go on. Lammy’s findings have reverberated throughout Oxford. I’ve witnessed students and staff alike remind themselves of the systematic bias toward wealthy, white, privately educated students, all in agreement that it is, indeed, ‘very bad’.

During the interview period, a staff member for access and admissions at my college explained that ‘after the whole David Lammy thing we all have to pull our weight a bit more’. Each college will now be given a larger “target” area, she tells me and the other interview helpers, and the bid to encourage more students from Northern Ireland will no longer be the responsibility of just St. Catherine’s and New College, but will be centralised. This is progress, but ‘pulling our weight a bit more’ is clearly not enough. The bulk of students and staff alike remain reluctant to fight against Oxford’s reflexive racist and classist admissions process. The first step to changing Oxford will be acknowledging that the systematic bias Lammy identified is not some incidental feature of the University which can be brushed off as merely a ‘thing’, an irritable fly we will eventually swat away. Instead, Oxford’s elitism needs to be confronted head on.

The problem is, this is not the first time this conversation has been had. In the midst of working at my college during the interview period, I stumbled across the 1978 copy of The Isis quoted above. ‘Oxford entrance is less than comprehensive’ argues David Wastell. Reading his article is a painful case of dejà vu.

Based on the statistics published in The Isis in 1978, 45 per cent of Oxford places went to state school ‘maintained’ students, with 15 per cent going to direct grant grammar schools and 38 per cent to the independent sector (and 2 per cent to overseas students). Now, the Oxford website boasts 59 per cent of its cohort taken from state schools, an improvement of fourteen percent. Although this may appear to be an improvement to the diversity of Oxford’s social landscape, the data fails to distinguish between students taken from grammar and state comprehensives. Grammar schools may not be fee-paying, but they offer their own form of educational privilege, filtering out students whose families can’t afford tuition for the 11-plus, or simply don’t place emphasis on educational achievement so early in the child’s life. While less than 5% of pupils in England attend grammar schools, it would not be far-fetched to bet they make up a healthy chunk of Oxford’s ‘state’ admissions statistic. The university is reluctant to release figures that detail exactly what this split is. This only suggests that the ratio is much less than representative.

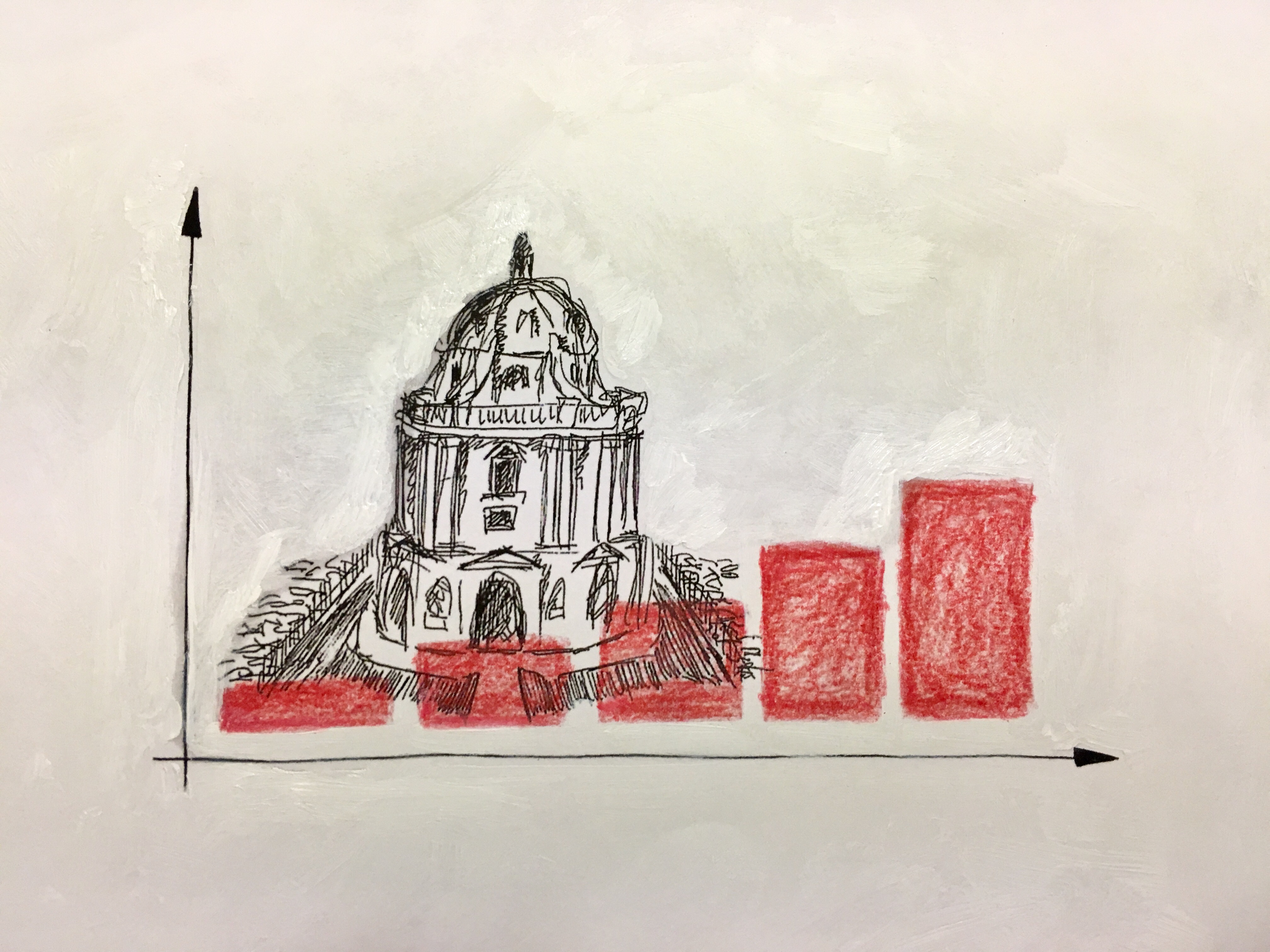

Even if we were to accept the 59 per cent of non-fee-paying school students as a progressive number, it seems that since 1978, Oxford has increased its ‘state’ school intake by just fifteen students per year. This is a crude statistic, of course; naturally, we can assume that much of the 14 per cent difference was made up in more recent years. But it still stands to show that adding on half a classroom’s worth of pupils from the ‘state’ sector each October is a pitiful excuse for social change. Whatever Oxford is doing, it’s not enough. In 1978, Wastall argued that ‘it is not enough to concentrate further educational privilege on those who are already the product of a privileged education’. He is right. And he was right nearly forty years ago. So why do Lammy’s statistics paint the same old picture?

Lammy is right to point the finger at admissions; after all, the people making the decisions about who gets the places must be ultimately responsible. But the backlash against his article protested more nuance to the situation. As was acknowledged by Wastall in 1978, much of the problem lies with students from the targeted state school backgrounds being reluctant to apply to an institution with such an intimidating image; they’d rather go somewhere “normal”. But this is not to excuse the university and place the problem entirely with the media’s portrayal. Access schemes should be about more than feeding state school students a different version of Oxford to counteract its reputation. Whilst there are many ways in which the university can be considered “normal”, we cannot turn a blind eye to its persistent elitism. I have heard rumours that the wealthiest students and their families are routinely invited by my college (though I am certain that St. Catherine’s cannot be the only college guilty of this) to special events, such as rugby matches or dinners with the Master, designed to secure donations. Pragmatic, sure – but also evidence of yet more networking opportunities presented to the most affluent. At the many Freshers’ Week drinks receptions with various college officials, the question I was asked most was ‘what school did you go to?’. Not only from fellow students, but from the Master, the tutors and other staff members. Being reminded every time you answer ‘you won’t know it’ that you are not part of this exclusive wealthy club does not make for a welcoming environment. I have even heard that the seating plan at matriculation lunch is based on the students’ household income, with those at the top of the social hierarchy placed closer to the Master. This may not be true, but the fact that it is entirely believable is testament to the unavoidable atmosphere of exclusivity that is hard for state school students to penetrate, even once they’ve earned a place here. No wonder not enough of us are applying. The problem is not that not enough state school students can access the “normal” Oxford behind the myths; the problem is that the Oxford behind the myths is not “normal” for anyone except those in the highest social classes. Oxford won’t appear as anything other than a finishing school for the privately-educated elite until it stops being exactly that.

It would be naive to assume that Oxford hasn’t changed at all. Working at interviews has been enlightening and refreshing in many ways. I’ve spoken to hopeful applicants from Manchester, Jersey, Carlisle, Northern Ireland and Yorkshire, among other places, suggesting that the geographic divide that Lammy highlighted could be dissolved. The interviewees also represent a much more racially diverse group than any of the years at my college. Perhaps I am being optimistic too quickly – this is the first time I’ve worked interviews, and so I’m yet to see whether the diversity translates into the offers made. But the fact that students from these backgrounds are even taking the time to apply (and managing to secure interviews) is undoubtedly a good thing. The change, as much as it should do, will not happen overnight. In fact, if Oxford continues admitting state school students at the rate it has done since The Isis’s investigation in 1978, it will be another 21 years before state school students, who make up 86 per cent of the UK, make up 86 per cent of the offers made.

I am unsure that we’ll ever get to this point. It’s hard to make progress when it feels like there are obstacles at every level. Toby Young – a man who admitted himself that he only got into Oxford after daddy made a phone call – was appointed earlier this year to the board of the Office for Students. The person now responsible for representing the interests of all students is the embodiment of the university’s bias toward the most privileged in society. The fact that it goes without saying that this is a ridiculous step backwards should not deter us from saying it anyway. If I’ve learnt anything from the depressing sense of history repeating itself between the 1978 issue of The Isis and now, it’s that we should definitely not stop saying it. It’s old news – nearly forty-year old news, at least – but that should not stop us from reminding ourselves and everyone around us that Oxford’s social divide is unacceptable. I am interested to see if the offers made in January reflect the supposed shock that Lammy’s article ignited – let’s hope they do. And if not, we’ll continue bringing up the issue, like Wastall, and like Lammy, for at least 21 years.

Artwork by Isabelle Davies