The Problem with Facebook

by Tilda Coleman | December 17, 2017

Like most people my age, I used Facebook throughout my teens. I still check the site every day, several times a day. Realistically, I check it several times an hour. Yet using Facebook never sat easily with me. It put me on edge, and I always vaguely meant to consider the exact reasons for these feelings. A recent ISIS article, however, highlighted the positive impact the site can have on social justice. Facebook can be a force for good, and many are becoming alert to the importance of utilising this potential. Yet the way I grew up on Facebook did not reflect this usage. When I first made my account, it was just a distraction; like a new toy to play with. As I progressed through school, the site gradually inserted itself into the background of my daily existence. It was still a distraction, but it also became an organisational tool, a way to talk to friends, and a place to find information.

It wasn’t until I read another article, by Zadie Smith, that I could articulate my general unease with this kind of everyday Facebook. The article, entitled Generation Why, reviews the film The Social Network before broadening out into a general critical consideration of Facebook. Smith argues that every aspect of Facebook can be traced back to the mind of its creator. I use ‘mind’ in the broadest sense of the term; Facebook is a product of Mark Zuckerberg’s thought processes, social standing, race, upbringing, class, and sexuality. That means the site reflects the mind of a young, white, male programming prodigy. The precursor to Facebook, it’s trial run, if you like, was a site called ‘Facemash’, which put two photos of Harvard undergraduate women side by side and asked its user to choose the ‘hotter’. After this was shut down, Zuckerberg used the same technology to create Facebook. Although the site that we know has undergone huge changes, in some ways its basic layout still harks back to the original function of ‘Facemash’. It’s set up in a way that encourages users to judge each other instantly based on a photograph. Chose a picture to encapsulate you, Facebook asks, one quick, easy means by which others can decide if you are hot or not. Only now, your profile picture doesn’t just communicate how attractive you are, but how worth knowing full stop; how fun, or quirky, or interesting, or aloof.

The site mirrors the worldview of its student creator in other ways. Smith writes about how a trait common to many young people is a desire to categorise, to package life into understandable aphorisms. Facebook encourages you to select a relationship status, summarise yourself in a bio, pick a religious belief and list your family connections. The site asks that you simplify yourself into flat, digestible little chunks. But do you really know anything about someone if you know that they’ve had braces removed? That’s an option in the ‘Health and Wellbeing’ section, right next to boxes labeled ‘organ donor’ and ‘new eating habits’. The simple placing of these various experiences in one ‘section’ of life speaks to an extreme tendency to categorise. More jarring is an option in the ‘Family and Relationships’ section to select ‘loss of a loved one’. The distance between the information asked and the format used seems insurmountable to me; the experience of grief is compressed to a click on a screen. Once you realise that the social media titan is a product of a young Zuckerberg programming away in his room, other aspects of the site become ridiculous. To communicate with another person online, you can ‘poke’ them; which is, as Smith says ‘what shy boys do to girls they are scared to talk to.’

Using Facebook is equivalent to being in Zuckerberg’s mind – down to the smallest of details. The site is blue because Zuckerberg is colour blind, and can see blue best. It’s one thing to ask what mindlessly subscribing to Zuckerberg’s location of value says about us. Personally, I don’t like the way Facebook defines me. But in a way, that’s just life; I watch plenty of adverts and shop in many places that appeal to ways of thinking that don’t reflect my own sense of self. The more urgent question is whether the site has the potential to define us, whether it could change our interactions, and even our brain chemistry. In You are Not a Gadget, programmer Jared Lanier demonstrates that software is not neutral. Each software is embedded with its own personality, its own value system. What infuses Facebook is a desire to flatten us, to get rid of, as Smith puts it, ‘our bodies, our messy feelings, our desires, our fears’. Lanier claims people ‘reduce themselves’ to make a computer’s descriptions of them more accurate. Being on Facebook can’t replicate the experience of being an embodied person; listing your favourite food is a pale substitute for eating it. Even laughing at a good meme can’t take the place of actually laughing with another person in the real world. And yet we all spend time, sometimes lots of it, participating in these inferior forms of physical life. Is my unease because I sense that this is fundamentally changing us?

We all know the obvious dangers Facebook poses to young people, how online manifestations of offline behaviours have led to cyberbullying, sexting and privacy issues. Yet more subtle are the effects the site may have on communication skills, particularly between generations. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, parents often lack ‘understanding that kids’ online lives are an extension of their offline lives’, and that consequentially a ‘disconnect’ may have resulted in how they communicate with their children. My little brother is thirteen. Every day after school he spends at least a couple of hours online. It must be the norm among his friends, because he spends a lot of that time messaging them, or tagging them in memes. They’re not talking about anything important. In fact, they’re probably not talking about anything at all. Zuckerberg places emphasis on ‘connection’ as both the means and the ends of his site. Yet recent research suggests social media encourages weak, superficial connections. My brother is enjoying his inane chats, though, so what’s the problem? Well, at his age, I used to tell my parents about my day at school during the car ride home. We had to talk; there was nothing else to do. I used to read books. He would obviously rather be online than engage in either of these activities. When he has friends over, instead of speaking, they sit tapping away in time together on their phones. More than an apprehension, this is a fear; that constantly engaging in meaningless chat on screen may deprive my brother of the real.

In broader terms, it’s hard to miss recent revelations about the sinister ends to which Facebook can be manipulated on national and international levels. The site sells space, for advertising and content, and during the US election, Russian backed pages created posts that reached millions of Americans. What scares me most about this is how targeted Facebook allowed the posts to be. One anti-Hillary advert repeated a speech from 1996, in which she used the term ‘super-predators’ to refer to black men. This appeared exclusively on the News Feeds of African American voters in areas where Republicans were trying to suppress the Democrat vote. Facebook knows your race, and it knows where you live. Anyone who pays Facebook enough can know this, and so they can first infer your susceptibilities, and then put targeted news there on your screen. Think what Facebook knows about you. Then consider Mark Zuckerberg’s views on privacy: ‘that social norm’, he believes, ‘is just something that has evolved over time’.

Despite all this, Facebook obviously has immense practical benefits. At Oxford, it’s impossible not to organise your life around it to some degree. All its knowledge about its users generally amounts to targeted recommendations, in the form of advertising products, suggesting articles to read or events to go to. This isn’t exactly harmful; you may find it a little annoying, or conversely useful. The fact that Facebook knows which Buzzfeed quiz to invite you to take, or that you’re likely to be interested in an event your friends are going to, could be viewed as increasing enjoyment and efficiency. And many features of Facebook make it easier to make real life, meaningful connections.

But ultimately Facebook is a business, and the more time you spend on it, the more money it makes. How many times have you messaged someone instead of going to see them, because it’s easier and you can’t really be bothered? And how many times have you bailed or been bailed on through Facebook? Being able to meet up with anyone at any time, and to easily click ‘not going’, inspires a frustrating lack of real-world commitment.

I’m writing this on one Desktop. On another, I’ve got Facebook open. I’ve checked it a couple of times over the last half an hour. Practically, it’s going to be a while before I can even think about deleting Facebook. It’s just too useful. At least I now have a better sense, though, of why I feel I want to.

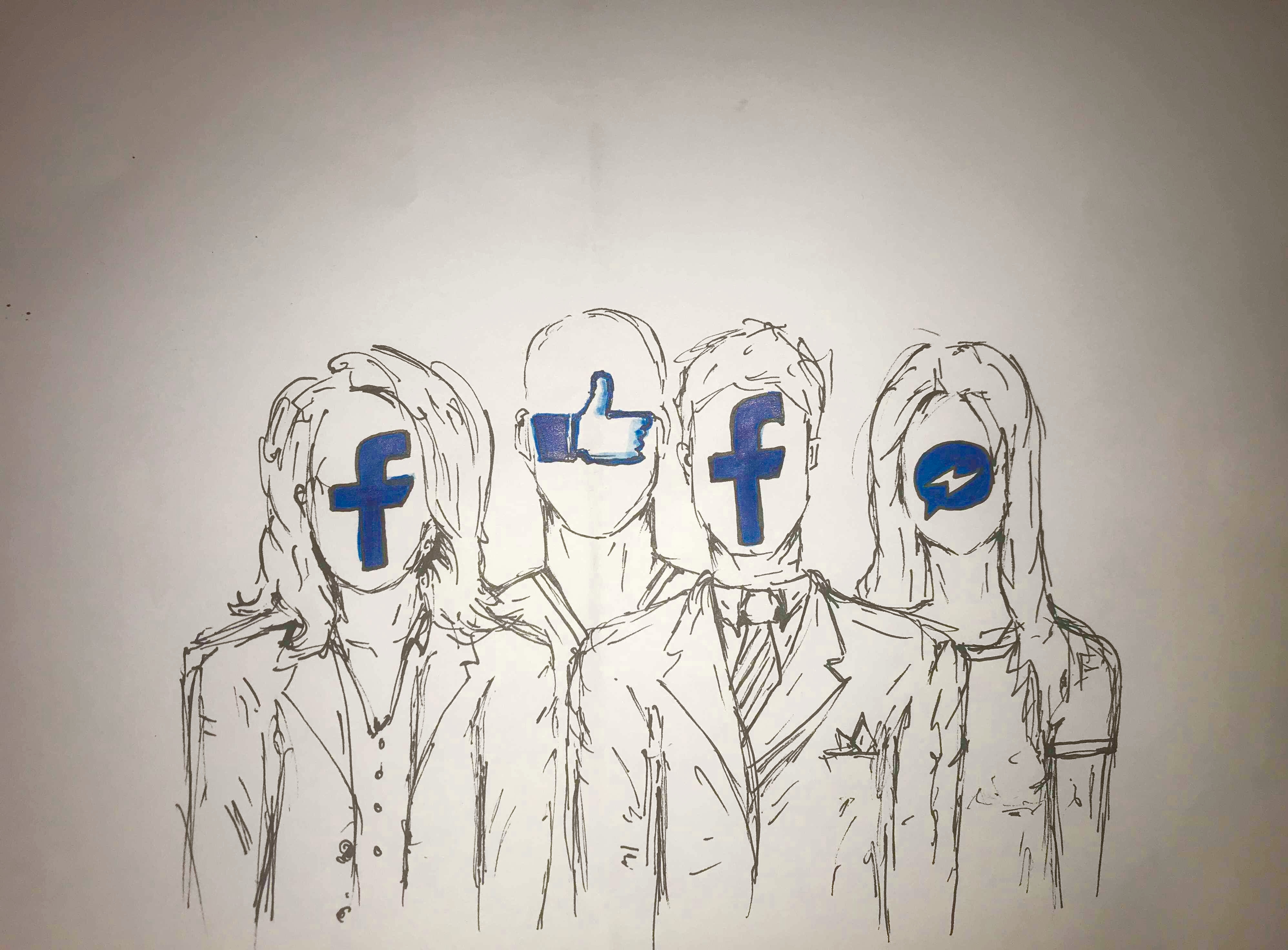

Artwork by: Georgia Heneage