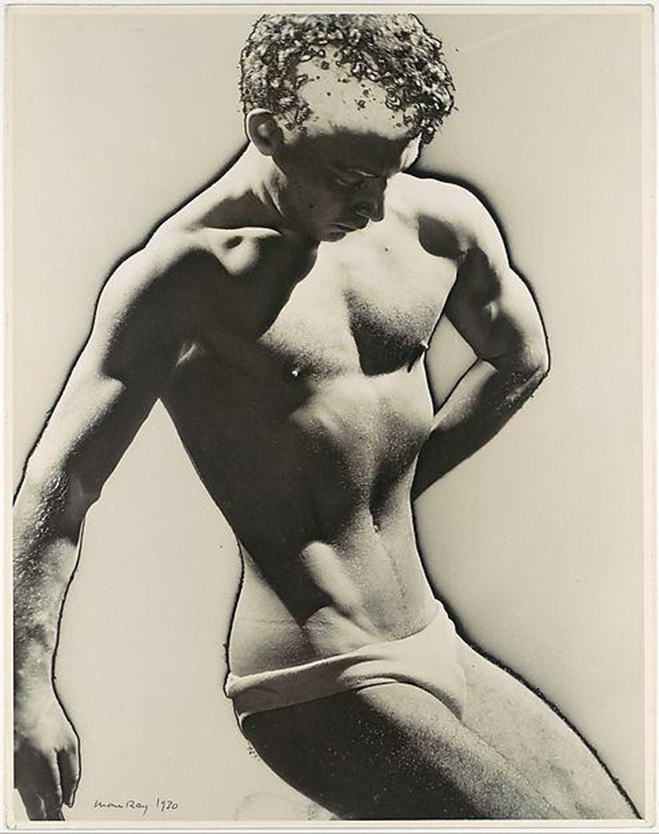

Male Nude, Man Ray (1933)

by Clarissa Mayhew | July 26, 2017

I remember my primary school art teacher exclaiming with impatience over a rather wonky still life sketch of a shoe: “Where are these black lines you’re drawing? Do you really see them?” What she meant was that real things, made of matter, don’t appear with black felt-tip outlines. Man Ray’s 1933 ‘Male Nude’ however, does. A studio photographer primarily, in contrast to the photographers thus far featured in this series, Man Ray exploited the complete control of the enclosed environment to conduct technical and visual experiments. These experiments challenged the reputation of photography as a medium for representing the ‘simply there’: for freezing the human eye in an eternal, reproducible sight. Instead, images like this, produced by a technique of solarisation—the effect of a sudden burst of light during the development process—show a vision that has never existed outside the photograph.

Across his oeuvre, from these solarisations to his Duchamp-inspired “readymades”, Man Ray was drawn to the critical space between art and life—bridging and manipulating the two to create images that are surreal. Here, the totally blank background abstracts the figure from any lived environment, his body protruding from the frame on three sides into who-knows-what. The angles of the muscular physique form diamond shapes of the body, gathering to a narrowness at the waist, and reaching pinnacle breadth at the jutting elbow and projecting arm. The downcast, darkened face and sculptural form of the body combine with the anonymous title ‘Male Nude’ to complete the de-personifying of the human into an aesthetic object.

It is the photographic process that is foregrounded in this image. The unnamed model is not so much the subject of the photo as the object upon which light, shade and chemicals react—too far even in the patch of overexposed hair, light-bleached into obliteration. Tiny details, however, maintain a sense of vivacity; the exaggerated points of the nipples, the fuzz of hair shading the outer arms and legs, the concavity of the stomach looking as though it is just about to breathe in—alive.

Paradoxically, the live subject here is shown quite alien from all conditions of living; it lacks a human context—an old sofa, evocative of cups of tea and conversations, or a garish picture on the wall—the attributes of everyday life. Comparable might be a single painting on a gallery’s blank wall, abstracted from a furnished environment precisely to emphasise its difference from mundane appliances. Ray’s black outlines potently highlight the natural human form while simultaneously severing the subject from reality by reducing it to the purely aesthetic and projecting it into the surreal. Man Ray’s photographs, with their determinate artistic significance, helped to solidify the position of the medium as a fine art, and his work in fashion photography introduced a new tradition of creative quality in the industry.