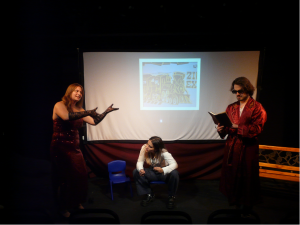

The ISIS review: Copenhagen, , Pilch Studio 19th – 22nd October MT16

by Frey Kwa Hawking | October 22, 2016

Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen revolves around the meeting of Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr in September 1941, the words exchanged between them and the race for nuclear fission in the Second World War. The longstanding but now precarious relationship between the two scientists is examined by the characters who are both removed from and pulled back once more into the action, and there’s no comfortable divide between physics and politics at all. Rupert Stonehill as Heisenberg stands up from the audience with his first line, but in his suit he could be any conservative Oxford student come to watch, and that’s fitting. Watching, we play the part of the surveillance which hangs about the characters like an “infectious disease,” and are implicated as they are. We know who achieved fission first, and so do they, but the play still worries at the wound.

Nothing can remain in the realms of the theoretical when in the midst of Nazi occupations, one’s own Jewish heritage, and deciding between assimilation and resistance. In their questioning of each other the actors cross to the white grid covering the walls and floor from the more domestic corner with its chairs and hat-stand. Copenhagen has a stake in representing the monumental impact each individual can have upon the history of the world, so the hanging baubles from the ceiling could equally be atoms or far-off planets.

The “deeply awkward occasion” is redrafted, by the characters, again and again; this is Frayn at play with people who collide like particles or waves, and he gives us, through the imagined conversations, shades of the truth, even if it was hardly as elegantly-realised as this. If Bohr and Heisenberg feel responsibility for each other, their countries and the people of the world, Frayn is as aware of this responsibility, and unspools the interaction with considerable compassion. From skiing and table tennis to the Bohrs’ parental feeling for Heisenberg and their grief for two of their own children, subjects shift in the rather heavy-handed stage fog.

Indeed the script was altogether more solid than the acting, often frantic but lacking a depth to the voices. Miranda Collins as Margarethe, however, was bright-eyed and composed, her speaking not entirely naturalistic but still sharp and strong, and even better when her gestures landed. Her role as Bohr’s other half, sounding board and typist gives her yet another way of pulling apart the past which Frayn had the sense to include.

The first half achieves such a deserved and painful point of clarity that everyone was surprised when we had to be told that it was only the interval, and while the second half of Copenhagen continues to be well-written with moments of beauty, it doesn’t reach any higher. The script makes us forget the “smell of drama student” which the people sitting next muttered about; we feel for the characters, and we feel for everyone.