“An artist is just a regular person”: An Interview with Koki Tanaka

by Thea Bradbury | August 25, 2016

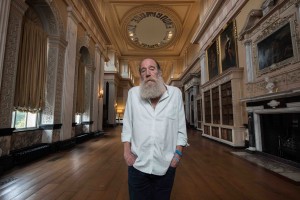

Koki Tanaka is perhaps the contemporary art world’s quietest radical: a man who, since being selected as Deutsche Bank’s Artist of the Year in 2015, has proceeded to gently undermine the very concept of ‘the artist’ in favour of encouraging collective action and historical responsibility. Against a cultural backdrop of blockbuster shows led by big-name artists, he is self-effacing to the point of invisibility, using performance pieces to shift agency onto the viewer and bring communities together—while apologising frequently for what he self-deprecatingly characterises as his bad English. I caught up with him during his first UK solo show to find out how his work has developed since winning the Artist of the Year award, and what’s next for him.

Tanaka’s Deutsche Bank prize exhibition in Berlin was my first encounter with his work, and its calm insistence that the viewer take on the burden of making meaning from it had me instantly fascinated. The exhibition, A Vulnerable Narrator, was his first solo show, and the pieces on display were given a deliberately rough-and-ready look, filling the marble and glass of the bank building with makeshift plywood stands and descriptions of the works printed roughly on brown paper. While A Vulnerable Narrator was presented as a retrospective, Tanaka did not arrange it chronologically; instead juxtaposing works to draw connections between events such as the 2011 London riots and the nuclear disaster at Fukushima. “A ‘retrospective’ is a way of looking back at what a person has done,” he says, “but at the same time the perspective is always from the present moment. So it is a way of reconstructing and re-reading the past.”

Since this exhibition, Tanaka’s interest in the past has only grown. While curating A Vulnerable Narrator, he was also working on a new project in Kyoto, documented at his most recent exhibition—and first UK solo show—at The Showroom in London. The project drew on the history of the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, which served as an army base during the US occupation of Japan and later became a key site for the post-war Japanese art scene. “It was just by chance that I learned such a thing from the curator. He told me the largest gallery space was turned into a basketball court by the US army, and later Christo did a fabric installation in the same space.” While Tanaka’s project featured re-enactments of many of these events, his intention was not merely to reconstruct the past, but to expose the influence it still has today: “US army bases are still a problem in Japan, mostly in Okinawa, and sixties and seventies conceptual art has a huge influence on our generation of artists. So I found something quite ‘now’ in the past … so the past is not the past. The past constructs the present, and in this sense, of course, the present constructs the future. Looking back at the past is thinking about the future, in a way.”

This recurring theme of the past’s inescapable influence is counterbalanced by the optimism of the collective actions that form a key part of Tanaka’s work. His ongoing series Precarious Tasks is shot through with post-Fukushima fears of nuclear disaster; yet it also offers hope in the form of community. Precarious Task #15: Exchange of our Clothes and Books as Exchanging Our Body and Thoughts (Reconfiguration), part of the Showroom exhibition, invites visitors to bring a favourite possession to the gallery and exchange it for one left by someone else, in the hope that this will inspire them to look at the world in a different way. Tanaka provides the initial impetus for this action, but makes no attempt to influence its outcome. This self-effacing strain is common in many of his works; when I ask how he relates to the idea of authorship, he replies that, “I do not really believe in the 19th century model of the artist as a genius, an extraordinary individual. An artist is just a regular person.”

Instead, he describes himself as a ‘situation maker’ whose aim is to ‘document the process of how collaboration works’. One of his best-known works, A Piano Played by Five Pianists at Once, provides an analogy for this attempt to abdicate his own authority. A video of the performance plays in the corner of The Showroom, sending jerky snatches of music through the gallery as its participants repeatedly try and fail to coordinate their contributions to the piece. Tanaka compares the way he creates his artworks to the “process of negotiating authorship of playing the music, and trying to reach equality through collaboration.” However, he acknowledges that it is impossible for him to truly remove himself from an artistic situation he has instigated, even with Piano: “Of course at one point, one of them calls me and asks my advice. It reveals my presence there as a frame maker/situation maker—but I don’t have any musical skill so I just step out again and they must decide it by themselves.” The exchange of books and clothes at The Showroom, which will go entirely undocumented, is perhaps the closest it’s possible to get to a complete renunciation of artistic authority—not ‘giving a model to look up to’, but simply offering a different way to view the world, as viewers try to determine what makes the objects left by their fellow gallery visitors so significant.

That Tanaka’s work is usually implicitly rather than explicitly political makes his latest show, at the Liverpool Biennial, all the more striking. This summer, Tanaka will recreate the 1985 schoolchildren’s strike against the Thatcher government’s Youth Training Scheme, with the involvement of some of the original participants and their children. He describes the current government’s work experience scheme as a ‘historical reincarnation’ of YTS, which used students as ‘cheap labour’. It’s the most political statement I’ve heard him make, and an indication that, however tentative and self-effacing his contributions to the art world may appear, they are underpinned by a clear socio-political vision. When he closes our interview by telling me that, for his next work, he’s “planning to use an out of function nuclear bunker as a venue for a series of workshops on the theme of how we can live together”, it seems the perfect consummation of his crisis-haunted, quietly optimistic career. For all his postmodern emphasis on breaking down traditional concepts of authorship, Tanaka’s efforts to build community through his works might be his most radical action of all.