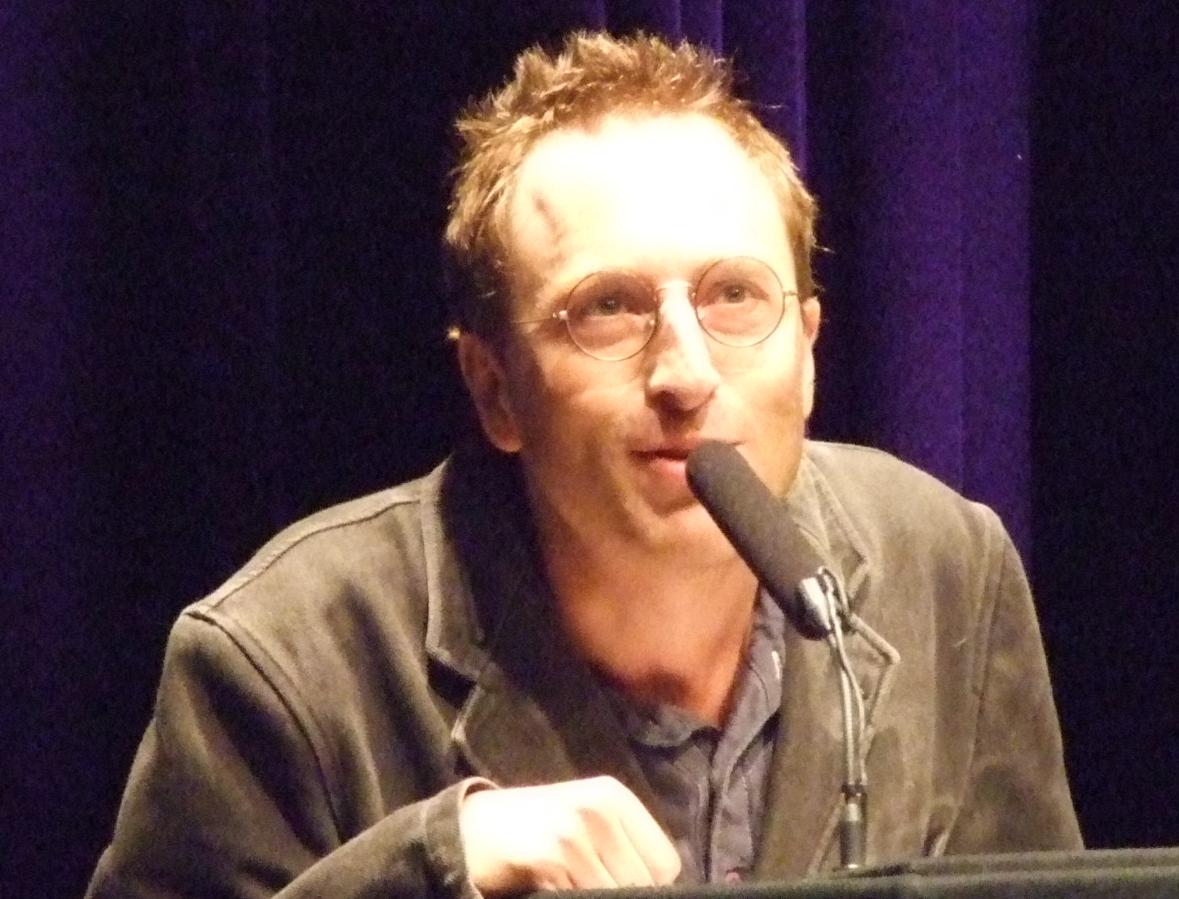

“I’ve become like a shame imam”: Interview with Jon Ronson

by Lulu Smyth | January 27, 2016

Jon Ronson’s face pops up on Skype. He peers at me through distinctive round glasses. “Do you mind if I quickly make myself a coffee?” he asks, then proceeds to take the computer around his New York apartment. “Here’s my study,” he says. “Do you want to see my dog? That’s New Jersey across the river. …The coffee machine is about to make a loud buzzing sound.” (Incidentally, the coffee machine sounds like a lawn-mower. It emits a grunt so deafening that I have to momentarily remove my earphones.)

Best known for his witty and thought-provoking non-fiction, including The Men Who Stare At Goats, The Psychopath Test and, most recently, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, Ronson moved from London to New York three years ago, where he now lives in the Upper West Side. How does it compare living in the US, I ask him? “It’s OK, as long as there are Brits around.” Pause. “Actually, I do like it. I really like it. I notice flaws when I go back to England now, like the gym. I’m going to be spending about a week in London and I checked the gym opening times. At weekends it’s ten til six, and I’m like: ‘What is this, the fucking nineteen-seventies?!’ In New York it’s six a.m. til eleven p.m., even on, like, New Year’s Eve.” The trip to England that Ronson is referring to underpins our conversation: on Sunday, the thirty-first of January, he will speak about public shaming at the Oxford Union. In anticipation of this talk, I ask him about social media and the culture of shaming in the twenty-first century.

In the first chapter of So You’ve Been Publically Shamed you discover a spambot of yourself, created by academics at Warwick University. What was it about that episode that inspired you to write on shame? Is that when the penny dropped?

I think so. It’s funny: things lodge in your mind without you quite realizing why they’re of significance. Something that the guy said to me, one of the academics who had made the spambot … We had this conversation about identity. His point of view seemed to be that your personal identity wasn’t important, and in fact in these internet days your identity isn’t even your own; your identity belongs to everybody.

I was surprised at how annoyed I was to have my identity taken away from me. I was thinking: ‘God, it’s taken me all these years to work out what my likes and dislikes are, to work out what kind of person I am. And here it is being snatched away.’ That’s such an unexpectedly violating thing for other people to do—to determine what your identity is.

There are echoes of that idea in your previous books too.

The Psychopath Test is all about mental-health labelling and what happens when you have a label like ‘psychopath’ pushed on to you. Again, that’s about somebody else determining your identity. Sometimes the person being called a psychopath is a psychopath, and sometimes they’re not. I thought about all of that, and then it hit me that this is what we’re doing all the time on social media. We’re labelling people, we’re reducing people to the craziest tweet they ever wrote, and it’s creating a whole new way of being.

What really struck me was that I was going around the world giving talks about my book The Psychopath Test, and everybody was agreeing that the over-labelling of people is wrong, reductive, inhumane. And then we’re all going home and doing exactly the same thing on social media. The hypocrisy of that annoyed me. Everybody loves to attack abuses of power when that’s happening over there, but when we’re the ones abusing our power, doing exactly the same thing that we’re attacking other people for, we hate it. When we’re being accused of that, we respond in a really ferocious way. So that’s why I wanted to write the book.

You’ve spoken in nostalgic terms about the early days of Twitter: how it used to be a curious and empathetic space, but it’s now become a stage on which people conduct “high dramas” and cast their fellow Tweeters as victims or villains or heroes.

It happens every single day, and sometimes it’s deserved. Sometimes the transgression deserves censure. But then, other times, it possibly doesn’t. There’s one that’s happening right now, as we speak—the singer Sam Smith. I mean, I’m not going to get involved in this one because life is too short. [Laughs] If I said on Twitter what I’m about to say to you now –

Careful…

I would get torn apart. But basically, Sam Smith was out last night with his friend in London, and his friend got some racist comments, and Sam Smith was upset on behalf of his friend, and fired off loads of tweets about upset he was, how he didn’t expect this kind of thing to happen in London. These tweets were slightly clunkily worded, but he was trying to be a good person, you know? He was trying to say the right thing. Then of course, Twitter set off, and as a response, the mainstream media too, because the mainstream media just goes along with everything that Twitter says these days because they’re pathetically grateful to have some kind of clickbait. Everyone’s saying: “Oh, thanks for whitesplaining”, and it becomes an attack on his white privilege. People misuse their privilege, that’s very true. But now he’s been mocked across social media for ‘whitesplaining’ when he was just trying to do the right thing. That sort of coldness, when it happens day after day after day, means that Sam Smith is getting treated with the same level of mockery and ridicule as someone who deserves it. It’s so knee-jerk, and it’s the opposite of the way I want the world to be.

Do you find since you’ve published the book that you’re made more aware of public shamings? Whenever there’s some sort of debacle—Tim Hunt, Matt Taylor—I always check to see what you’ve thought about it. Do these people ask you for advice?

I’ve stopped. I’ve gone out of that game. I tell you who did contact me though—I haven’t told anyone this. The prosecutor in the Making a Murderer case.

I was going to ask you about that!

Yeah, he contacted me thinking that maybe I’d write a piece about it. He was upset that the documentary makers brought in the fact that he’d been done for sexting. He felt it was unfair of them to mention that in the documentary. I emailed back saying I didn’t think it was unfair; I thought that in the overall context of the documentary it was not inappropriate for them to mention it. And then that was it.

What do you make of the criticisms of the programme?

Like everybody, I loved Making a Murderer, I thought it was one of the best ten hours of television I’d ever seen. I think the criticisms of that programme could mean that people drop the ball and forget what’s important about it, which is that they were definitely documenting a miscarriage of justice, whether or not Steven Avery did it. They were shining a light on judicial bias, and they were quite possibly uncovering the fact that the police set those people up. At the same time, when I read about the stuff that they’d left out of the documentary, I did feel slightly lied to. I wished they’d put everything in. I mean, Sarah Koenig [the creator of Serial] would have put everything in. You shouldn’t go too far down that road, though, because it was a brilliant series about something important. When Ken Kratz emailed me, I thought that even though I do have some problems with the documentary, I’m not sure that he was unfairly treated. That’s why I didn’t think, even for a second, that I would write about him.

That sounds fair enough. So it sounds like you’ve become a Messiah figure for the publically shamed.

My friend John Saffron, who’s an Australian journalist, says I’ve become like a shame imam. [Laughs.] That’s not good! Because you don’t want it to overwhelm your life. I write lots of stories about lots of different things, and this year I had a story which I was really proud of about actors of Middle Eastern descent in Hollywood, who find they can only get work playing terrorists.

I remember that, yeah.

I loved that piece and I’m really proud of it, but no one’s asking me to comment on that. They’re asking me to comment on shamings at the moment. So I suppose what I’m saying is that my days as the shame imam have come to an end, really.

I think it’s important for journalists to move onto other stories. Otherwise you become the journalist who only talks about one thing. As much as I do care about this issue—and at times I felt like I was part of a campaign, you know, I’d have breakfast with Monica Lewinksy and stuff—I also feel it’s really time to move onto other stories. Otherwise you become a kind of caricature, and that’s not me.

It’s easier to fall into that, too, if you’re writing about social media as well as being on social media. It’s a constant connectivity thing—people know you’re interested in it, and can contact you on it, with questions about it …

Exactly, it becomes a sort of whirlpool. Especially if you spend too much time on Twitter, it can become all that matters. Things take on provenance on social media that make you feel, sometimes, that it’s the most important thing in the world when it isn’t necessarily. At other times, something can happen on social media that really does take over somebody’s life, like with Tim Hunt or Justine Sacco. It really counts, it makes an impact, and can upend someone’s life.

What about public bereavement? If there’s one thing that the internet likes to do more than shame, it’s to grieve.

Yes. I remember when Robin Williams died, I didn’t immediately notice, and I tweeted that tickets were on sale for an event I was doing. Everyone was like: “Oh my god, I can’t believe it, how dare you.” I mean, it’s kind of subjective because with someone like David Bowie, he was such an enormous part of my life that I felt that the public bereavement was appropriate. He mattered a lot to people, including me. In some other cases, I feel slightly … I feel like something else might be going on. There sometimes seems to be a bit of a fear there, like insisting: “I’m a good person”. This fear is a real problem! I’m not going to say anything about Sam Smith on social media because I know what will happen: I fear the reaction. As a journalist, that’s not what we should do. We should be fearless. We should speak truth to power. There’s a fear happening at the moment that is stifling free thought and creativity.

As a final word, what’s the antidote to that?

I think there’s a good chance it will burn itself out in a positive way, where what’s important is real social justice and real civil liberties will continue to matter. This kind of flotsam-and-jetsam, this “cathartic alternative” to social justice will wither and die. I honestly think that at the extreme end of the social justice movement, those that misuse that power are in danger of ruining it. It’s bad for everyone.

Jon Ronson is speaking at the Oxford Union at five p.m. on the thirty-first of January, 2016.