The canvas of literature

by Alys Key | December 11, 2015

Affecting and often disquieting, the work of Naomi Alderman does not quite prepare you for the author herself. She is playful and witty, her fiction somewhat more serious. Since 2006, she’s published three novels that trace very different paths through painful subjects. In the first, Disobedience, a woman returns after her father’s death to the Orthodox Jewish community she grew up in and must confront the broken relationships she had seemingly left behind. The novel draws heavily on Alderman’s memories of her own upbringing. The narrative voice hovers between first and third person, drawing the reader into an intensely personal criticism of “the hot-house of humanity that is the north-west London Orthodox Jewish world”.

“I’m fundamentally motivated to write in various ways about systems that have made me angry,” she admits. Indeed, the first-person passages may be in the voice of Ronit, the novel’s protagonist, but “Often it’s because I’ve been personally affected by them in some ways.”

This is something she explores in her subsequent novels. Her second book, The Lessons, is set in Oxford (she graduated from Lincoln College in 1996). Once again, it is an unflinching look at the difficulties of existing in a tight-knit community, and she even suggests as we discuss the concept of the ‘Oxford novel’ that Oxford “can be a site of trauma.” Her most recent book, The Liars’ Gospel, enters into the realm of historical fiction, exploring the aftermath of the death of Jesus from the perspectives of four characters. “Writers,” she says, “like to revisit some trauma with a long perspective.” They span different times and places, but her novels are all tied together by their focus on the most devastating emotions in human experience: grief, love, and loneliness.

Even a cursory knowledge of Alderman’s life makes it difficult not to pick up on the parallels between her own experiences and her first two novels. I ask her about this, and whether when writing them she had a sense of confronting elements of herself.

“Oh yeah,” she says readily. “And the same is true of The Liars’ Gospel … possibly I’m just getting more subtle about how I communicate that I’m confronting things that have annoyed me! With Disobedience, when I started writing it I was an Orthodox Jew, and after it was published I wasn’t anymore. So I certainly worked something out of my system with that book.”

Disobedience changed its author in more ways than one. It was by no means a quiet debut, and quickly pulled Alderman into the spotlight, earning her the Orange Award for New Writers, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, and a Waterstones Writer for the Future Award in the process. Its frank confrontation with faith and community sets it apart from other contemporary London novels, depicting a world to which only someone who has been an Orthodox Jew can allow the reader access.

Transitioning from that world to Oxford is another memory still perceptible in her fiction. She admits that she would find the stress of starting university difficult to deal with even now, never mind as a young adult.

“Three days after I arrived”, she recalls, “was the start of the Jewish festival of Succot.” This complicated her start to term, as she wasn’t allowed to do any work other than reading for three days. Combined with the lack of kosher food provided by her college, it all proved somewhat overwhelming.

“When I arrived at the Jewish society on the first night of Succot—I think it was Thursday of 0th week [the first week of term]—I was sopping wet from trying to find the building in the rain and promptly burst into tears.”

Although James, the narrator of The Lessons, never appears to be particularly aligned with any religion and comes from a mundane middle-class household, his sense of isolation and insecurity seems tied to that of his author.

“I think it took me years and years to think through what had happened to me at Oxford,” she says. “I arrived very intellectually confident and left thinking that I was very stupid and useless.”

It is perhaps a familiar story to many of us: the big fish leaving the small pond and finding themselves overwhelmed not to be a big fish any more. “Like every student in Oxford, I had only been the best,” reflects James in an early chapter of The Lessons. “To be average, to be ‘normal’, seemed beyond humiliation to me.”

She does not glamourise the university as the glossy, rose-tinted Oxford you can find on a postcard on Broad Street. Still, one half-expects those who write about the place to recall it with the wide-eyed, awestruck tone of the traditional Oxford novel. Indeed, The Lessons does have its dreamy moments: a hidden mansion in the middle of Jericho, misty morning jogs by the river, hushed conversations while the college choir sings in the evening. But it’s also deliberately dark, an attempt to uncover what Brideshead leaves unvisited.

“I wanted to write something that was in conversation with Brideshead Revisited, that was about the actual pressure of the work, which Waugh blithely skims over in his novel, and about how terrible people don’t actually get rescued and perfected by ineffable grace. What happens is that, unless and until you stop them, they will go on destroying you, inch by inch.”

Despite this cynical approach, Alderman has a gift for taking the worst elements of life and turning them into something beautiful, or at least worthy of being written about. Even when I ask her for her happiest memory of Oxford, she offers a painful recollection of falling in love “almost constantly and almost invariably unrequitedly; I was probably madly in love with ten different variously inappropriate men while I was at Oxford and, though it was terribly painful at the time, those memories have softened into something sweet and beautiful, as love almost always does.”

Even though she wrote a full novel between her first and second years at university—a feat she wishes she’d realised at the time was quite beyond most other 19-year-olds—Alderman took a while to gain enough confidence as a writer to make it her career. “I showed [the novel written over the summer] to some Oxford friends who were less than complimentary, and then I didn’t show any more of my work to anyone for eight years! Goodness, young Naomi!”

She may have overcome that now, but it would be short-sighted to see those three acclaimed novels as standalone pieces in her progression as a writer. She has also written a Doctor Who tie-in novel, and writes for games, including the smash hit exercise app Zombies, Run!

“There’s clearly more cultural cachet in writing literary novels than in writing videogames,” she says, as we discuss whether one form of work ought to be valued over another. “And so I enjoy the cultural cachet, and I enjoy the very personal, intense work of bringing a book into being. But Zombies, Run! has about 2,000,000 players now, and a good sales figure for a literary novel is maybe 60,000 copies? So…”

“Games do just bring my work to a wider audience, even though the sense of ‘oh, this is important’ still resides with novels in this very curious culture-lag way. I care about the quality of the work in each case, I never want to be putting something into the world with my name on that I don’t believe in.”

Yet her upcoming novel, The Power, toys with the kind of themes which might unite her game-playing audience with her literary readers. “The short version”, she tells me, is that “almost all the women in the world suddenly develop the power to electrocute people at will. They can do anything from a mild tickle to full-on killing blow. So the silhouette you have to be most afraid of coming towards you in a dark alley is different. And then everything is different.”

When I suggest that her turning to sci-fi might shock those who have loyally followed her literary work so far, she seems nonplussed.

“A lot of my favourite novelists like to move between genres. Doris Lessing moved from realism to sci-fi, Margaret Atwood moves between contemporary novels, historical novels and dystopian futurism, Toni Morrison’s Beloved is a ghost story, Virginia Woolf wrote the gender-bending weird and magical Orlando as well as Mrs Dalloway. Even John Irving wrote some sci-fi. The canvas of literature is broad: why confine oneself to only one corner of it?”

That “canvas of literature”, such an intimidating concept for many writers, appears to be just a plaything in the hands of Naomi Alderman. In sharply assessing what makes us tick, from the fear that motivates users of Zombie Run! to the isolation of The Lessons, she has created a body of work which never fails to both surprise and comfort the reader.

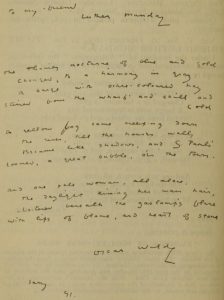

Image by Fr Lawrence Lew, O.P.