What Online Campaigning Has Taught Me about how the Media Presents Sexual Assault

by Ione Wells | August 23, 2015

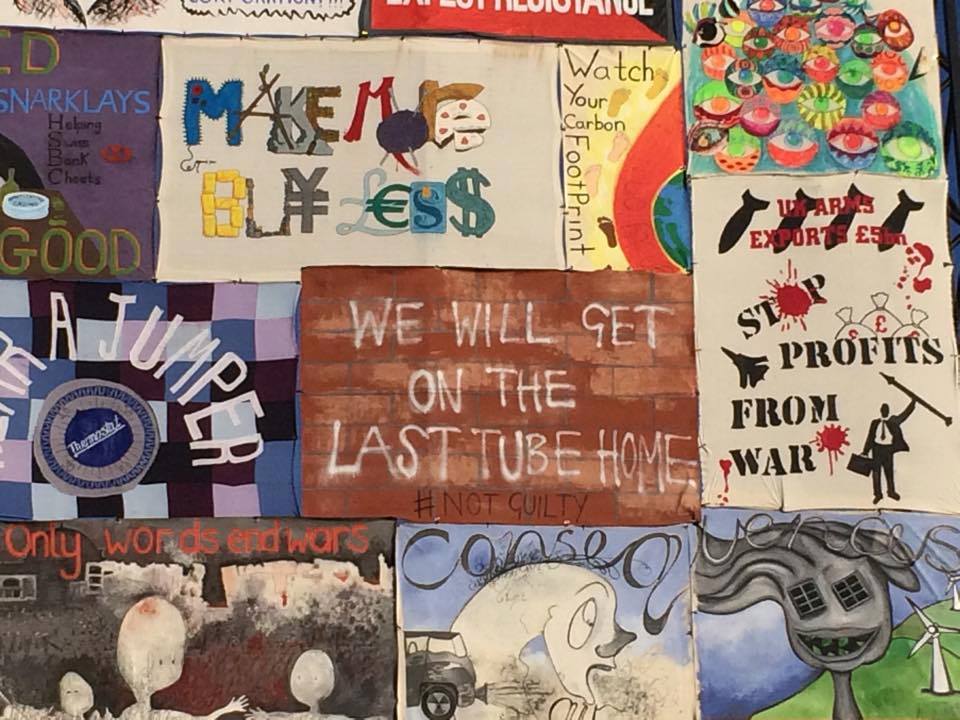

As with almost all projects, one tends to learn much more about the issues that you are grappling with, or the problems that you are trying to solve, once the process is already underway. Since I began campaigning against sexual violence and victim blaming with the #NotGuilty campaign in April 2015, it has become increasingly obvious that the very platforms that I used to launch it are also where some of the most crucial change is needed.

There is no one way that sexual assault should or can be presented in the media. The ‘Shared Stories’ project that I have created on the #NotGuilty website allows people a platform to speak out, but it also seeks to show that no two individuals speak of an experience of the same nature. We can’t compare “I’ve known this guy for 2 or 3 months” to “Suddenly everything looked different. Maybe I hadn’t been the incredibly mature and sophisticated young woman who had attracted an older man” to “my attacker was someone who I have known for a long time, someone who I have cared for deeply and always trusted”. We can’t compare “six years ago” to “only last week”. We can’t equate how individuals were affected by assault, and what is therefore best for them, as the stories also show how the consequences manifest themselves differently. We can’t relate, “I was so embarrassed” with “I am still confused today”, or “my family were amazing…and they have really helped me. Telling them was a huge relief and I recommend anyone to do the same” with “I still feel shame, guilt, worthlessness.” All of these statements are voices that I have received through the campaign, and all of them represent the huge variety of ways in which assault can happen, and can affect somebody.

But, unfortunately, we still tend to be surrounded by the illusion that there is a so-called “typical” assault, despite the fact that the stereotyped late-night, dark-alley, stranger, DNA-under-the-fingernails case is actually, statistically, a very rare type of sexual assault. One is much more likely to be assaulted by somebody that they know. Portraying limited images of what assault is not only fails to educate individuals about the nuances of consent, but can also make victims of, say, domestic assault worry about reporting, or receiving help about, their assault for fear that it won’t be taken as seriously or believed.

One comment from a reader of an article about the campaign struck me, as it questioned whether it had been easier for me to speak out because I was a “good victim”…whatever that means. I can only presume that by “good”, the commentator referred to a victim of an assault that can be neatly portrayed in the media because a stranger committed it, the case was reported and the perpetrator was caught. But this so-called “good victim” image is damaging on many levels. Firstly, no kind of assault is ever “good” for the victim, at all. In fact, it is really, really devastating and hard. But, more significantly, applying qualifiers to the victim, rather than the crime, suggests that the victim is someone whose status or actions plays a part in defining the assault, or that they are somehow complicit in it, and that other victims thus may be somehow less ‘valid’ or ‘good’ than others. The commentator may have not thought these things, but the pure choice of semantics shows that these attitudes and presentations of assault are embedded in how our culture treats and, more crucially, presents assault as both something that has one “true” form, and as something that the victim can be partially blamed for. Even the NHS, under Jeremy Hunt, seriously put up posters in surgeries saying, “One in three reported rapes happens…when the victim has been drinking. Alcohol: know your limits.” At the heart of any stereotypes, or any definitions of what makes a “good” or “bad” victim, is the idea that the victim in some way could have done something differently, which is in essence the exact victim blaming that the campaign seeks to abolish. Furthermore, the dark silhouettes of figures, the dimly lit dark alleys – these are all images that the media gives us on a day-to-day basis. We hear about the rape that happened at 3.14am under the bridge by the nightclub and the 6ftsomething that the police are looking for, but we don’t ever hear about the assaults that happen everyday in the home, for example, despite the fact that both these cases would be equally destructive and, critically, rape.

There are indeed reasons, which the commentator may have been trying to get at, why people are less likely to speak out after a marital or familial assault, an assault by somebody they know, an assault by somebody who was not caught or an assault by somebody that they had consented to sex with before. People may feel ashamed or the need to be “loyal” to the perpetrator, they may feel like they would be judged by others or not be believed, or they may feel guilty, as if it was their fault for being around that person despite the fact that they could never have controlled somebody else’s abusive actions. There is also the issue that because certain terminology, such as the word “assault”, cannot be used in some platforms without a conviction, those whose perpetrators have not been caught or reported can sometimes feel that this also limits them from getting help and support, which is not true. What has become apparent from speaking to survivors through the campaign who have felt such things is that a large problem underlying all of these feelings is that people do not hear about situations like theirs often enough, and therefore feel like they are alone, or even that their assault doesn’t “count” because it doesn’t match the images of it that they have seen in most of the media.

It is amazing how, as soon as a few people write about feelings like the ones above, or their personal experiences of assault, more and more voices begin to speak out and get help. If it were normalized to discuss all types of assault, and the complexities of consent, I would feel hopeful that fewer people would feel these things in the first place. The same applies to how people are affected by it. Speaking at the Clear Lines Festival a few weeks ago about intimacy after assault, I heard several individuals say they had felt like a “freak” for having problems with body image or intimacy after assault…only to find that the whole room had felt the same things, and everyone had just never heard others talk openly about it before.

Until speaking about a full range of sexual abuses becomes as normalized as speaking about murder, theft or any other crime, society will continue to be at risk of making victims feel blamed if they do not conform to those assaults that are presented, and potentially preventing many individuals from reporting their case and seeking help. A full spectrum of voices and individuals of all genders, ethnicities and sexualities, and a full spectrum of cases from stranger attacks to incest or marital rape, must be presented for our media to reach full representation. I was not attacked on a dark alleyway, but on my own road, and that is still a lot further from home than the average attack.