Hymn to Intellectual Duty

by Daunish Negargar | July 23, 2015

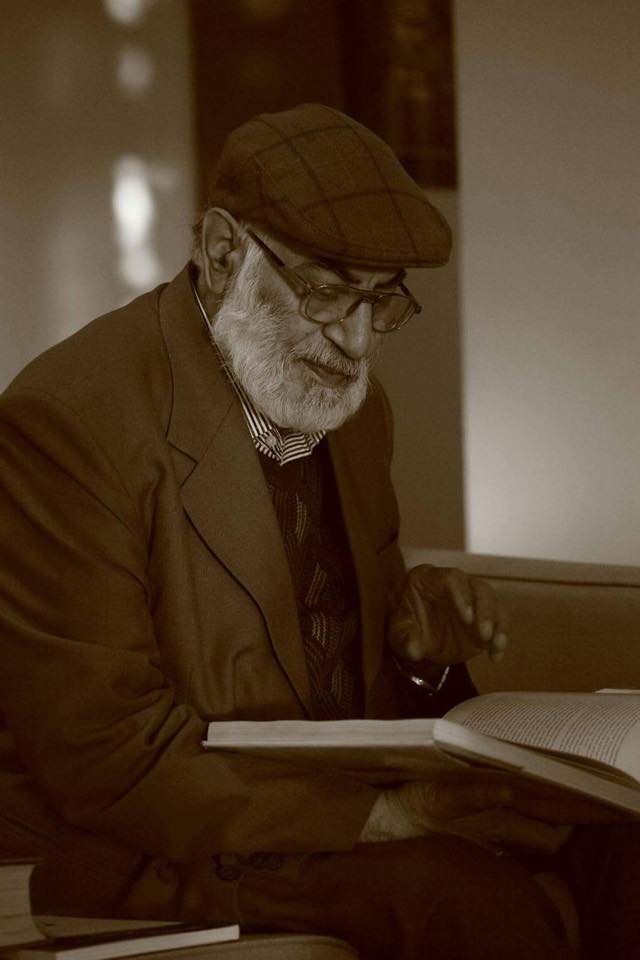

The phrase ‘political prisoner’ is charged with both power and notoriety, concepts I had never associated with my 75 year old grandfather. To me, he has always been my baba, a former English teacher whose days are spent writing poetry and tending to his garden. I’d heard my parents talk about his arrest on occasion, but had always assumed it to be some kind of inside joke on my family’s part. When I finally ask him about it during one of my weekly visits, I expect the long-awaited punchline. I am instead met with the jarring news that my grandfather became a political prisoner when he was arrested on the 22nd of May 1982, for his opposition to the Soviet-led Afghan regime. His house in Kabul was broken into, and he and his brother-in-law were taken into custody by the authorities. Within a week he had been transported to the now infamous Pul-e-Charkhi prison, which was to become renowned for the torture and execution of over 25,000 political prisoners between 1978 and 1986. He was incarcerated for almost a year, during which he was kept in solitary confinement. Visits were totally prohibited. As he tells me his story, sat in his study, the situation begins to take on an air of surreality. Hearing this extraordinary tale, and then relating it to my grandfather is difficult. And yet, whilst his experience is remarkable, I have since discovered that it is just one of many harrowing personal stories, told by ordinary Afghans who became prisoners of a regime which divided and fundamentally changed their homeland, and left scars on its history which remain unhealed.

The Saur Revolution of 1978 occurred when the first secular government in Afghan history was overthrown by the PDPA (People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan). The PDPA was divided into two branches, the more moderate Parcham branch (taken from the Farsi word for ‘Flag’) and the radical Khalq (or ‘Masses’) branch. After the revolution, the Khalq branch began to implement radical reforms in Afghanistan, which included changing the traditional Afghan flag to a red one, similar to that of the Soviet Union. Considered an affront to Islam, these reforms led to widespread revolts in the Afghan countryside, which were eventually quashed by the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. The leader of the Parcham branch, Babrak Karmal, was appointed as President in 1979 by the Soviets, in the hope that his less radically communist presence in office would provide some stability. Under the guidance of Russian officials, Karmal oversaw the establishment of the National Fatherland Front, an umbrella group to the Parcham branch. They had been tasked with recruiting new members to the communist party, in the hostile political environment that was Afghanistan. “Members of the National Fatherland Front had heard my poetry readings at demonstrations in the 1960s, and wanted me to write propaganda for their cause.” explains my grandfather. “When I refused, I was imprisoned. They were a regime born of an invasion, a puppet regime. I didn’t want to write for them, or anyone. I kept telling them ‘I’m just an English teacher’, but they wouldn’t listen to me.”

When I ask him to describe the conditions he lived in during his imprisonment, he is hesitant. This isn’t an easy conversation to have with your grandson. “My cell was two metres long by three metres wide, with a toilet at the back of the cell, and a straw mattress to sleep on. The smell was awful. We were allowed to bathe only once a week, for fifteen minutes, in cold water.” He never experienced torture personally, but often saw it occur. “Every day in winter they would make prisoners line up and make them jump into a pool of ice cold water. They forced them to stay there for hours on end.” When I ask him to describe the hardest part of his imprisonment he doesn’t falter in his response. Having gazed many times at the shelves of books that have lined his living room since I was a child, I find his answer unsurprising. “I didn’t have any way of reading books. I didn’t even have a pen or paper. To them, having a pen was as dangerous as having a Kalashnikov.” he explains wryly. As he

speaks, a note of pride creeps into his voice. “I would write my poems on toilet paper, with used match ends, left over from when I’d lit my cigarettes. I could only write a line or two before the match would break.” It seems that even during his imprisonment, his will to write and his freedom of expression proved difficult to repress.

Throughout his time in prison, he was asked time and time again to join the National Fatherland Front. His constant refusals eventually led to the threat of execution. When I ask why he didn’t give in and join, his response is calm and measured, as though he had never even considered there to be an alternative. “When you’re in a third world country, writing under a dictatorship, you can’t be creative, because the government forces you to write in favour of them, and against their enemies. It’s a prearrangement, and writing isn’t possible through prearrangements.” Despite numerous threats, the Soviets eventually realised he would never be an ally to their party, and my grandfather was eventually released in the spring of 1983, almost a year after his imprisonment. He returned to his home in Kabul, and was finally reunited with his wife and son. Within 6 months, they, along with my mother, had fled Kabul for Peshawar, a city near the Pak-Afghan border. In the face of mounting tensions between the Soviet Union, and Muslim groups opposing them, they applied for refugee status to the UK. By March 1989, their application had been approved, and they came to this country, to the three bedroom flat in Birmingham, where I was born.

Later, he shows me one of the poems he wrote in prison, neatly transcribed into a battered black notebook. Within the poem, he describes the need for the people of Afghanistan to become ‘khud-shinaz’, a Farsi word, which roughly translates to ‘self-knowing’ and ‘independent’. When I ask him if he feels as though Afghans have achieved this goal, he seems torn. “While I was in prison, I kept hoping Afghans would learn something from this despotic regime, but they didn’t. They never became ‘khud-shinaz’. For every step forward, we seem to take two steps backwards. Just the other day I heard about the murder of Farkhunda, and it frustrated me, because it feels as though Afghanistan is regressing, rather than progressing. When I lived in Kabul, the problem was die-hard Communism, and now it’s religious fundamentalism. It doesn’t feel like anything has changed.’ His slight despondence is a surprise, but certainly not unfounded. Just 3 years ago, the Afghan author Taqi Bakhtyari was condemned for his novel Gumnami (Anonymity), within which the protagonist rejected Islam, and questioned religious authority within Afghanistan. Copies of the book were publicly burned, and the author was subjected to death threats from religious scholars, and Afghan citizens alike. It would appear that words remain as dangerous in Afghanistan now as they were so many years ago, for both the regimes they speak against, and the men and women who write them.

Before I leave, my grandfather shows me another project he started in Afghanistan, and continues to this day. In a notebook entitled ‘Pearls from Other Cultures’, are a collection of English poems, translated into his native Farsi. I can’t help but ask him to choose a favourite poem from the collection. He pauses slightly, before pointing to his translation of Percy Shelley’s Hymn to Intellectual Beauty. As I read, one line in particular draws my attention, in which Shelley discusses the duty he feels towards the spirit of intellectual beauty.

‘I vowed that I would dedicate my powers

to thee and thine, have I not kept the vow?

With beating heart, and streaming eyes, even now.’

He doesn’t tell me why it is his favourite poem, and nor does he need to.