The Rise and Fall of Internet Poetry

by Sean Wyer | December 30, 2011

What if someone were to tell you that practically everything on the internet – from LOLcats to facebook chat conversations, from Viagra adverts in spam e-mails to inane tweets – was potentially of poetic value? That bloggers, and creators of viral videos and animated GIFs, play a similar role in our society to that that the disaffected beat generation poets did in theirs?

If we were to pick anybody to fight this corner fiercely and gallantly, it would be Steve Roggenbuck. Starting in 2009, Roggenbuck built up a vast internet presence as a creator and advocate of anything that could be described as Internet Poetry, a movement dedicated to “raising poetry to the level of internet culture”, rather than the other way around. After building a successful and thriving community around the concept, however, he is now distancing himself from the idea of Internet Poetry as a movement, saying that as he cultivated the project, “the word… started to feel like clutter to me”.

Perhaps this shouldn’t come as a surprise from somebody who has vehemently rejected genre distinctions and borders from the outset, urging people to “break free from the shackles of word” and to expand the term poetry to incorporate video, image and text combinations and GIF. Roggenbuck’s blog has repeatedly stressed that poetry is something he sees as loosely defined. Now, however, he sees the term as so loosely defined as to be more or less meaningless. He explains: “if we are really going to be open about putting language in various visual/multimedia forms– then why are we even calling it poetry as a rule?”

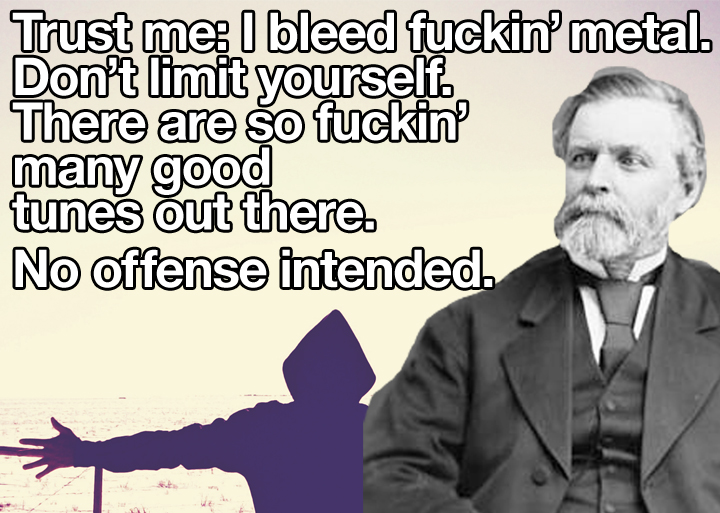

Roggenbuck’s waning enthusiasm for Internet Poetry as a concept might worry some of his loyal followers and fellow ‘poets’, many of whom have themselves built names for themselves under the term. Does this signify the death of the Internet Poem? Not exactly. He still speaks with great passion about the internet’s ability to facilitate literature, stating that it opens up “big opportunities for types of poetry that are maybe not respected in academic institutions but which actually have a big potential readership”. This explains his continued work in a similar vein to before, creating unlikely juxtapositions of text with out-of-place images.

When justifying his passion for an internet culture so regularly ridiculed for its apparent pointlessness, he writes articulately and passionately, a clear break from his famous online persona characterised by twitter-esque brevity and “post-ironic” sarcasm. “For me it’s really just culture. That’s the level at which I care about it: we are creating things that make other people happy and which tell us how to live.”