Afghan Woman’s Hour

by Treasa-Mae Bell | December 20, 2011

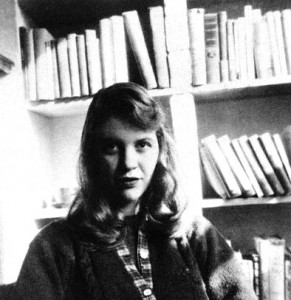

Zaraghuna Kargar, a short, brown-haired woman, is attentive as she escorts me to her sofa and selects an armchair for herself. As producer and presenter of the Afghan Woman’s Hour and the author of Dear Zari, she has defied the customs which imprison many women in her country. Set up by the BBC in 2005, the aim of Woman’s Hour is to broadcast a programme specifically aimed at women, cutting through social, economic and geographic differences. Aired in Dari and Pashto, it discusses gender, social issues and women’s rights, inviting doctors, psychologists and female politicians to provide information and opinions to women throughout Afghanistan. But the most popular section is when real Afghan women broadcast the individual stories of their lives, and it is these which comprise most of Dear Zari.

In the book, as in real life, Kargar radiates independence and candour. Dear Zari is a testament to her determination to provide Afghan women with a voice in a time when few are willing to hear them. Although many would say that such a liberated woman is an anomaly, she insists that all Afghan women are connected. In the book, Kargar chooses to interweave her life story with the other tales, creating the impression that she and the women are united. She explains: “I realised it doesn’t matter if an Afghan woman lives in London, she is still an Afghan woman and she will somehow suffer and go through the things that an Afghan woman is going through in North Afghanistan or another mother goes through in Kabul.” There is no better candidate to comment on the plight of Afghan women than Kargar herself; having unwillingly submitted to an arranged marriage, she divorced her husband to the astonishment and disapproval of her community. Kargar’s personal experience and journalistic work have given her both the sympathy and the experience necessary for raising awareness about the lifestyle of many Afghan women.

But what is it like to be an Afghan woman? “When it comes to relationships, when it comes to life, family, looking after children, in that sense I think women are globally similar. But when you look at the lifestyle, it is completely different, and even I as an Afghan woman – who had lived far away from my country and from the women I belonged to – found it shocking,” Kargar tells me. A palpable factor is the role of men; a woman is always under a male relative’s control. With bitterness Kargar talks of how women are seen as the property of their male relatives: “In many, many things, as a woman, you are just somebody who men of the family decide for: for your future, for your life. If it’s good or bad you have to live with it. That is that.” The marriage system enforces the perception of women as a commodity; it has been estimated that between 70 to 80% of Afghan marriages are arranged, and women are frequently forced to marry husbands selected by their families, regardless of her objections. Girls can be sold to settle family disputes and debts; Dear Zari is replete with daughters traded to settle old scores. The tale of Shereenjan is just one example: when her brother killed a man from another family, Shereenjan’s father traded his nine year old daughter in recompense. Now an old woman, she spoke on Afghan Woman’s Hour of how she grew up in the barn, slaving for the new family. Later she married the family’s eldest son and bore him children in lieu of the murdered man. She chose to end her story with the phrase, “this is the story of my life.”

“Women who have come out and try to speak about this and try to change this are supressed in many ways.”

“The face of woman is a source of corruption,” remarked a Taliban official in the 90s. “There are a big number of men out there who do think that women should be hidden,” Kargar remarks, with a shake of her head. And those men who don’t are concerned about gossiping neighbours and the scorn of their community, if their wives and daughters seem to be behaving scandalously. But what do Afghan women believe? Shockingly, some agree that they should be treated as inferior. “I think it is a culture imposed by men on them,” Kargar tells me, “because if you hear 24/7 from the man of the family ‘don’t go out without a burqua, it is shameful. Look, this neighbour did this, that neighbour did that, they don’t have shame or manners,’ then you start to believe that.” There are also women who defy such categorisations, but the choice is not easy: “Women who have come out and try to speak about this and try to change this are supressed in many ways. They are shunned by society, they are shunned by the men, and they are shunned by their fellow women who think they are not good women.” However, Afghanistan is rolling forwards: boys and many girls are receiving education, exposure to more tolerant perspectives and Kargar hopes for a more open-minded generation.

The combination of cultural restrictions, political confinement and war has worsened women’s situations substantially. “The consequences of war for women are far worse than for anyone else,” says Kargar. “If a woman is widowed she loses everything.” For a widow, remarriage means forsaking your children, but appealing to your in-laws and relatives means becoming a financial burden. In Dear Zari, Kargar introduces us to Layla, who after being widowed three times was shunned by her community as a “woman of dark steps.” Eventually she left her children and was forced to live as a servant in her brother’s house, reminded daily by her sister-in-law of her inferior status. Kargar sighs dejectedly: “I see that it is so widespread in my society. The widowhood, the pain, losing your kids, losing your name, being the subject of gossip.” In the 1980s, the Communist government established assistance for widows, providing monthly rations of essential imported items. But when the Taliban arrived the benefits ceased.

“Afghan society is very traditional and based on culture and traditions which are imposed by men and in favour of men. It is not even based on religious factors,” Kargar informs me. This year, as the tenth anniversary of military invention in Afghanistan approaches and talk of pulling troops out by next year grows, the prevalent attitude is that segregation is not the effect of a religious tyranny, but a cultural manifestation. David Cameron stated: “We are not there to build a prefect democracy, still less a model society.” Nevertheless, the West still has a substantial role to play. Even to compare the state of the country now to ten years ago before, the situation has improved tenfold. Before, Kargar tells me, “women literally had nothing.” Now there is education, women parliamentarians for the first time in Afghan history, women activists, media programmes specifically for women, such as Women’s Hour. Hussan Ghazanfar, Afghanistan’s minister for women’s affairs, on a recent visit to the UK, quoted that 57% of girls now go to school. However, Kargar fears the process ahead will be slow: “There will be heroes who go forwards for change, but even in England change didn’t happen so quickly,” she remarks with a smile. Indeed such progress is hardly received with open arms by many Afghans. Between March and October 2010, twenty girls’ schools were attacked, and in the same period at least 126 students and teachers murdered. The price to pay for education is still high.

“Afghan women are like sleeping lions: when awoken they can play a wonderful role in any social revolution.”

What is the role of Afghan women in creating change? Even under the Taliban there were those who covertly defied the laws. The Golden Needle Sewing School stands out as the salient example of a widespread phenomenon. Women met together under the pretext of learning to sew. In reality such gatherings were small classrooms, where they discussed a sometimes surprising, and eclectic, array of subjects, including James Joyce, geometry and Afghan history. These schools demonstrate Afghan women’s resilience and determination. In 2009, women protested against the Shia Personal Status Law, which decreed that any Shia woman could not leave the house without her husband’s permission, nor could she refuse him sex. The law was eventually softened. The truth however, is that this reflects only one section of Afghan women; especially in rural areas, old customs are prevalent. Organisations like RAWA – the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan – also have a major role popularising the plight of Afghan women. This group, founded in 1977, is the oldest organisation in Afghanistan fighting for liberation, peace and equality for women. Indeed, RAWA’S founder, Meena Kamal, remarked “Afghan women are like sleeping lions: when awoken they can play a wonderful role in any social revolution.” When I say this Kargar nods emphatically. “It is a very beautiful sentence and it is very true. In Afghan women the resilience I have seen shows it to be so.”