The Emperor’s New Clothes

by Barbara Speed | September 15, 2011

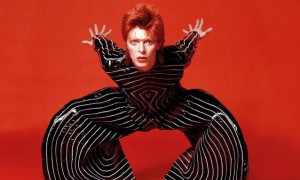

On April Fools’ Day 1998, the New York Art elite gathered to toast a new biography of the artist Nat Tate. Written by William Boyd, published by David Bowie and endorsed by Gore Vidal, the book was a welcome insight into the life of the reclusive artist who – everyone at the party agreed – they had all heard of but never met. Unbeknownst to the partygoers, Nat Tate was completely made up.

An amalgam of “National Gallery” and “Tate Modern”, the character was created by David Bowie and his co-conspirators to test how gullible the art world could be. The answer: very. Nevertheless, people were rather charmed by Bowie’s hoax, and Tate’s ghost haunts the art world to this day: his first ‘authenticated’ painting went to auction this year, and three documentaries have been made about him. He exists as a sort of cultural in-joke, a warning against excessive posturing and falsity.

Hoaxes range from Alan Sokal’s “postmodern quantum physics” paper to Ali Larter’s appearance on the cover of Esquire as Allegra Coleman, a fake film star with fake film credits.

But when it comes to pricking overblown cultural movements and exposing arrogant intellectuals, it’s not just the art world that’s been hit by subversive hoaxers. Max Harris, editor of Angry Penguins, an Australian modernist poetry magazine, was the target of a similar scam in 1944. He received a submission by a man called Ern Malley, and published it, declaring it as great as the work of WH Auden or Dylan Thomas. Yet Malley, like Tate, was invented: the creation of James McAuly and Howard Stewart, his ‘poetry’ was strung together in a single evening (sample line: “I had often cowled in the slumberous heavy air.”) The embarrassing episode caused considerable damage to the modernist movement in Australia.

Indeed, tricksters cast their nets far and wide with recent hoaxes ranging from Alan Sokal’s “postmodern quantum physics” paper to Ali Larter’s appearance on the cover of Esquire as Allegra Coleman, a fake film star with fake film credits. In both cases, as with Ern Malley and Nat Tate, the hoax was only exposed when the perpetrators revealed the joke.

Those confronted with such hoaxes all seemed to share the same response. They wanted to blend in – terrified of looking stupid, no-one would point out that the emperor was naked, the poetry faked, the maths meaningless. Lacking in whistle-blowers, academic fields seem remarkably vulnerable to deception, which suggests a dark conclusion: there may be many more intellectual cons which, unlike the examples above, have not been triumphantly unveiled.

Lacking in whistle-blowers, academic fields seem remarkably vulnerable to deception

In Time Immemorial, published by Joan Peters in 1984, may well be such an example. The book, which claimed that modern-day Palestinians are the descendants of recent immigrants to the area (thereby legitimising Israeli occupation and settlement), received rave reviews in the USA and was read by many academics. Among these was Norman Finkelstein, whose story was published by Noam Chomsky as a cautionary tale. Finkelstein, having found that no Arab sources were used, that the numbers quoted were misinterpreted, and that Peters’ conclusions seemed to be unfounded, tried to conduct further research but was stonewalled by the academic community. When he began a book about the issue, prestigious professors began to offer him jobs, research, anything, in return for dropping his project.

It isn’t clear whether this is the story of an elaborate hoax, misguided research or something more sinister. Whichever it is, the story is disturbing because it proves the endurance of the traditional tale’s ending: the Emperor, despite being told of that he is naked, stubbornly clutches his invisible cloak and continues his procession, valuing his pride more than the unpalatable truth.